Ruins are not usually inhabited. By their very nature, they tend to be abandoned, neglected and remote. Such places as Tintern Abbey or Rievaulx were not very hospitable once the original buildings, deliberately built far from centres of population, had been pillaged and made roofless. There can be ruins in city centres, of course, as in Rome or Athens, but antique structures tend to become hidden within later structures, or disappear into the rising earth, until resurrected by antiquarians and archaeologists.

Archaeologists are so often the problem. Certainly they are the enemies of the picturesque. The romantic charm of a ruin, whether classical or gothic, has so often been undermined by the removal of later accretions or by purist sterilisation: the old Ministry of Works treatment, with the ruined masonry cleansed of any sign of ‘Pleasing Decay’ and surrounded by immaculately mown lawns. To the archaeological mind, such things as later houses built in to medieval ruins are an affront. When the Ministry took on Bury St Edmunds Abbey in the 1950s, it was immediately proposed (happily, ultimately in vain) to expunge the charming houses built into its ruined west front on the grounds that the Ancient Monuments Act precluded taking inhabited structures into guardianship.

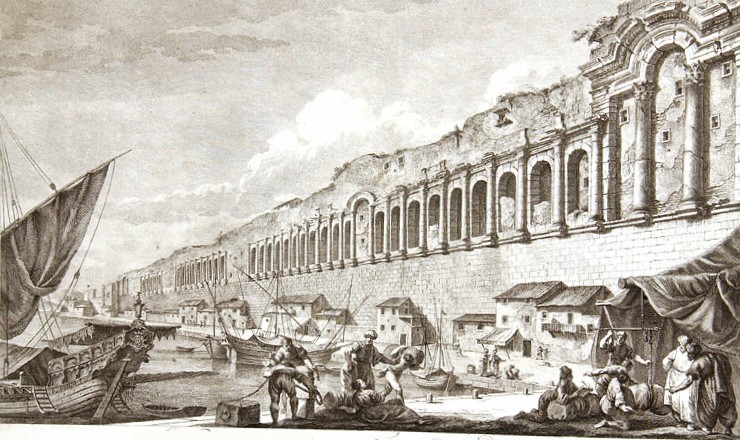

But there is one place in Europe where a great ruin is not only inhabited but is the very centre, the raison d’être of the city it adorns. This is Split – or Spalato – in Croatia, on a peninsular on the Dalmatian coast where the ancient core is the substantial, astonishing ruin of the palace of the Roman emperor Diocletian. It is huge: the seafront alone extends almost 600 feet. As Rose Macaulay put it, in her Pleasure of Ruins (1953), ‘It has always, both before and after it took on (in the seventh century) its present eccentric and unique appearance of a town enclosed in a palace, produced a stupendous effect on those who have visited it. It has been, possibly, the most serviceable ruin in the world.’

Diocletian’s Palace seems to have been completed by the year 305, in time for the emperor to retire from public life. Originally it was a large rectangle with corner towers and high walls. Gates penetrated the centre of each of the four sides – that by the sea allowing access to a massive vaulted basement. Above this was a long open colonnade, behind which the emperor had a viewing gallery. In the centre of the palace was a peristyle, an arcaded open space, off one side of which was the octagonal Temple of Jupiter, which became Diocletian’s own mausoleum.

Later, the inhabitants of the inland Roman town of Salona, fleeing the Avars, occupied the empty palace and made it a fortified town. In the words of Edward Gibbon (who never saw it), ‘Had this magnificent edifice remained in a solitary country, it would have been exposed to the ravages of time; but it might, perhaps, have escaped the rapacious industry of man. The village of Aspalathus, and, long afterward, the provincial town of Spalatro had grown out of its ruins. The Golden Gate now opens into the market-place. St John the Baptist has usurped the honours of Aesculapius, and the temple of Jupiter, under the protection of the Virgin, is converted into the cathedral church.’ Instead of the regular orthogonal geometry of the Roman builders, the internal courts became a dense network of irregular streets, housing tens of thousands. The original buildings and temples were adapted, mutilated, reused – a tall Romanesque campanile announcing that Diocletian’s tomb was now a place of Christian worship.

Under Venetian rule, along with all the islands and towns of Dalmatia, Spalato was isolated between the Adriatic Sea and the high mountains behind, beyond which were the Ottomans. The town was, however, known, visited and admired, but the full richness of its surviving Roman architecture was not documented until after Robert Adam’s visit in 1757. Seeking a novel subject to publish so as to advance his career after his years in Rome, the ambitious Scot decided to investigate what he (and Gibbon) called ‘Spalatro’, rather than ancient sites in Italy. Accompanied by his former tutor, the accomplished French artist Charles-Louis Clérisseau (who specialised in ruins) and two draughtsmen, he managed to make a reasonable survey in a short time despite having insufficient permits and being thwarted by the Venetian authorities who regarded the group as spies. The eventual result was the publication in 1764 of Adam’s Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia.

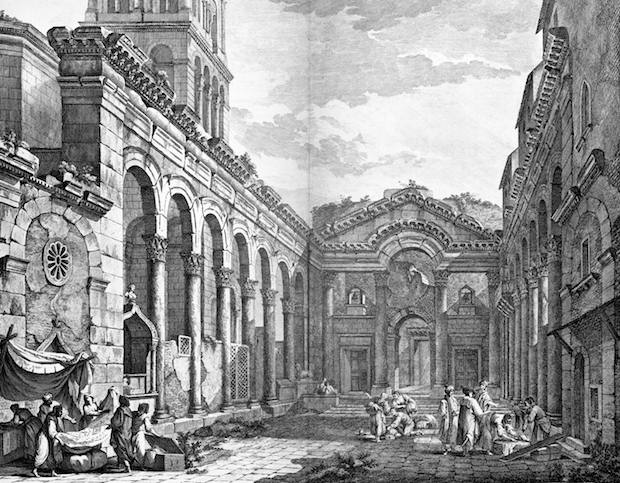

Charles-Louise Clérisseau’s view of the peristyle of Diocletian’s Palace, Split (1764).

This magnificent volume was a revelation, and changed taste in Britain – the plan and detail of Adam’s Kedleston Hall was one result. As an antiquarian survey it was not wholly accurate, however, as Adam attempted both to depict what he saw and imaginatively reconstruct how the palace originally looked. Apart from the Venetian military, the problem was, as he wrote, ‘first from the numbers of modern houses built within the walls of the palace and even upon its old foundations; secondly from the inhabitants having pulled to pieces and utterly destroyed some parts of the antique work; and lastly from their having so blended the ancient and modern work together by repairs and alterations that it was not without great difficulty they could be distinguished.’ But it is precisely these factors that make Split so fascinating and visually rewarding today.

The seafront of Diocletian’s Palace, as depicted by Charles-Louis Clérisseau (first published 1764)

Modern Split has expanded well beyond Diocletian’s walls. A handsome, more spacious new town grew to the west of the palace during the 19th century, when Spalato found itself part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And then, during the Yugoslav years, Split grew into a major port and industrial centre. But the ancient core is remarkably unchanged. Indeed, what is extraordinary is that the peristyle today looks almost exactly as Clérisseau drew it over two and a half centuries ago. There may now be plastic shopfronts, café umbrellas, bank machines and the other trappings of the tourist industry; the sublime vaulted basement may be filled with souvenir and postcard stalls; the peristyle may now be crowded with tourists and local guides dressed up as Roman legionaries, but the thrilling fact is that it is still possible to see Spalatro almost as Robert Adam saw it in 1757.

Split is a complex palimpsest, exhibiting the tangible remains of layer after layer of human activity stretching back to antiquity. It is alive, as thousands of people still live and work within the now ragged walls raised by Diocletian. If it were merely an archaeological site (as nearby Salona now is), picked clean of all later additions and alterations – the fate suffered by the Athenian Acropolis after Greek Independence – it would be far less interesting and not much to look at. As it is, the ancient core of Split is a precious wonder, the best of ruins as it is both grand and inhabited. For Rose Macaulay it was simply ‘one of the best examples in the world of picturesque life in a ruin’.

From the December 2016 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home