Few displays of Italian art in recent years have been as absorbing and beautiful as this unprecedented selection of paintings, drawings and prints, devoted to the brothers-in-law Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431–1506) and Giovanni Bellini (c. 1435–1516). The quality of loans in the exhibition, organised by the National Gallery in partnership with the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, is outstanding (the exhibition travels to Berlin from 1 March–30 June 2019). With the exception of a panel of St Jerome from Saõ Paulo, given to the young Mantegna, and the Portrait of a Humanist, attributed to Bellini, there are almost no questionable attributions among the paintings.

The visitor is greeted by a display of Jacopo Bellini’s sketchbook from the British Museum. Easily ignored, owing to the faintness of the leadpoint drawings, it in fact presents a rare opportunity to lay eyes on a volume that Giovanni used as a source of ideas and compositions – the argument could have been made clearer here if provision had been made to scroll through Jacopo’s pages on a computer screen. Elsewhere, works on paper, including superb examples of Mantegna’s vigorous penmanship, play a significant role, though strangely, given the prestige of prints by Mantegna, relatively few are included.

The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (c. 1505–07), Giovanni Bellini. National Gallery, London

Today, when instant communication allows far-flung families to stay in touch, it is easy to overestimate the likely contact between the brothers-in-law, particularly after Mantegna left Padua to take up residence as the court artist of the Gonzaga in Mantua. It is primarily Bellini’s earliest works, from the 1450s and 1460s, that reveal his response to his more precocious brother-in-law’s innovations. In compelling juxtapositions, the first rooms reveal just how precisely Bellini copied Mantegna’s fissured rock formations and emulated his command of body and drapery depicted from low or oblique angles in subjects such as the Agony in the Garden, the Crucifixion and the Descent into Limbo. But contrasts of inheritance and temperament are already apparent. In the earliest work signed by Bellini, the exquisite Saint Jerome in the Wilderness from Birmingham, we perceive how the colours are related to one another through modulation of light. And while Mantegna continues to use low viewpoints to create surprise and heighten emotion, his Venetian brother-in-law respects the calmer, frontal presentation of saints familiar to him and his patrons in the mosaics in the state church of San Marco.

Saint Sebastian (c. 1459–60), Andrea Mantegna. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Photo: Gilberto Urbinati

Essentially, for Mantegna the male body is the speaking body. The Crucifixion panel from the altarpiece for San Zeno in Verona – a star of the second room – presents a theatrical stage animated by many voices. On the left, St John cries out as he looks up towards Christ on the Cross, while to the right soldiers converse as they dice for Christ’s seamless robe. Similarly, a print of the Flagellation, based on Mantegna’s design, foregrounds Roman soldiers talking together with no regard for the torture of the innocent victim enacted at a little distance behind them. Repeatedly, Mantegna contrasts those who witness and those who turn their backs. In the small panel depicting St Sebastian, the archers returning home are oblivious that their arrows have failed to complete their job and that the saint, like Christ, triumphs over paganism and death.

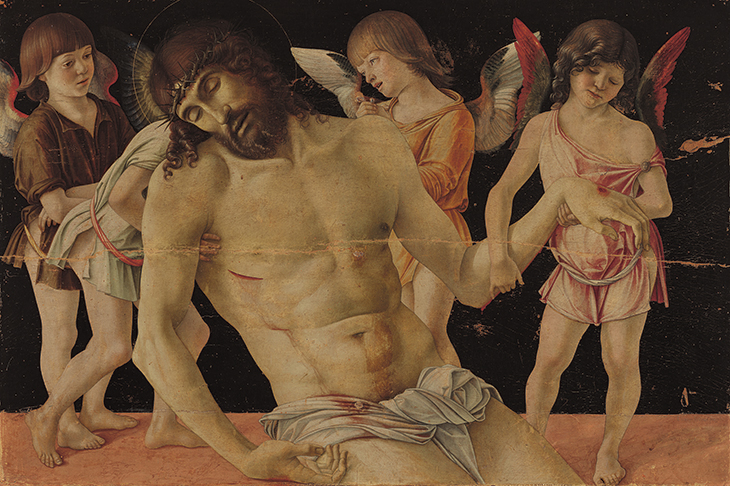

The Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels (c. 1485–1500), Andrea Mantegna. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Bellini presents his subjects without such dramatic irony. His figures rarely appear to speak, and the viewer is not directly addressed. In Mantegna’s later works, especially his allegories, words proliferate, carved in rock and inscribed on scrolls, whereas Bellini has no use for visible words apart from his name attached to a modest cartellino. In the third room, devoted to the theme of the Pietà or Dead Christ, Mantegna’s drawings show the three women who support the body crying out in grief, whereas in Bellini’s drawing the Virgin silently wraps her arms around her son, the pair alone within the cave-like sepulchre. In Bellini’s masterpiece from Rimini, The Dead Christ Supported by Four Angels, the mute eloquence of the wounded body belongs to a different world from the direct address and shrill emotion of Mantegna’s Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels from Copenhagen, hung in a later room dedicated to landscape. If Mantegna is theatrical in a mode that recalls Roman rhetoric and martial command, Bellini tends towards a Grecian stillness mediated by the presence of Byzantine art in Venice and by the sculpture of the Lombardo family. Both painters responded to Donatello’s sculptural reliefs in Padua, but it is Bellini who plays with overlapping figures to transcendental effect. Thus in the Rimini Dead Christ the head of the putto angel who leans in from the left disappears behind Christ and the wing of the same angel, fanning out to support the Saviour’s lolling head, intimates his future resurrection.

The Dead Christ Supported by Four Angels (c. 1470), Giovanni Bellini. Museo della Città ‘L. Tonini’, Rimini

The concept of landscape painting in this period was still barely defined: contemporaries referred to lontani (‘distances’) and paesi (‘places’). In the room devoted to landscape we notice how both painters construct their paintings by contrasting near and far, city and countryside, cultivated land and rocky wilderness. From the start, Bellini reveals a special tenderness towards animals, and proceeds by making places where animals dwell in association with humans. In the Birmingham Saint Jerome a donkey grazes peacefully in the middle distance. In one of the revelations of the exhibition, the recently cleaned Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr in the National Gallery’s own collection, the domestic animals in the middle ground offer a tranquil foil to the brutal martyrdom enacted before them. For Mantegna, by contrast, man is always in command. In his early religious paintings the sheep are painted in a perfunctory manner, while in his moralistic allegory Minerva Expelling the Vices from the Garden of Virtue, executed late in his career for Isabella d’Este, vice is associated with the bestial and personified by creatures that are half human and half animal. Such antitheses were foreign to Bellini. In his Feast of the Gods, painted for Isabella’s brother Alfonso, all creatures whether human, animal or hybrid, are treated with equal sympathy. This is just one of the many contrasts between these two great artists revealed by this endlessly fascinating exhibition.

‘Mantegna and Bellini’ is at the National Gallery, London, until 27 January 2019.

From the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home