‘Writings on the Wall’, Waddington Custot’s compelling show in the heart of Mayfair, takes as its starting point a particular body of work by a single photographer and traces its influence on the titans of mid 20th-century painting. The photographer is Brassaï (1899–1984), dubbed ‘the eye of Paris’ by Henry Miller, who began a 30-year-long project photographing graffiti on the city’s streets in the 1930s, classifying its signs and symbols, its depths and layers, with the seriousness of an urban archaeologist and ethnographer. For Brassaï, these were contemporary expressions of prehistoric petroglyphs and ancient Roman graffiti: ‘The language of the wall amounts to not only an important, and until now, little studied social phenomenon, but also to one of the most powerful and authentic forms of artistic expression.’

Brassaï’s photographs of graffiti were exhibited in New York, Paris and London in the 1950s and early ’60s, and published as a book, along with his conversations with Picasso on the subject, in 1961. In his writings, Brassaï reflected on the appropriation of ‘wall materials’ and ‘wall language’ not only by Picasso, but also by Joan Miró and Paul Klee.

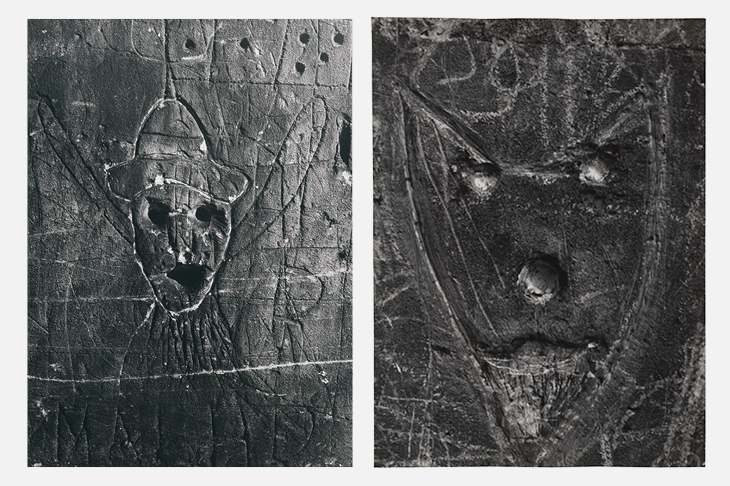

This show, part loan and part sale, focuses on six artists – Brassaï, Jean Dubuffet, Manolo Millares, Vlassis Caniaris, Antoni Tàpies and Cy Twombly – and, in effect, five cities: Paris, Las Palmas, Barcelona, Athens and Rome. In the silver gelatin prints of Graffiti de la série VIII, La Magie, Brassaï’s graffiti heads emerge – just – out of the gloom, revealing the photographer’s evident delight in how pre-existing ‘eye’ and ‘mouth’ holes in a wall called out to have heads and bodies drawn around them.

Pisseur au mur, 16 janvier 1945 (1945), Jean Dubuffet. Courtesy Waddington Custot

Nearby hang a row of lithographs from the series Les murs (The Walls), which Dubuffet began in 1945, a year after meeting Brassaï, to accompany poems on the subject by Eugene Guillevic. Here we find walls and their scribbled, calligraphic or pictorial graffiti. Pisseur au mur, 16 janvier 1945, for instance, is a purposely ‘deskilled’ or Art Brut streetscape with walls featuring those universal declarations of love – initials and hearts – alongside no less ubiquitous smutty cartoon genitalia. The painterly surface of his La chasse au biscorne of 1963, opposite, resembles a grimy wall itself with its gritty impasto incised with drawings and graffiti.

The self-taught Millares developed his dramatic, idiosyncratic ‘collages’ inspired by the petrograms of prehistoric Guanches people of his native Canary Islands and made using burlap, a material used in Guanche funerary ceremonies. Executed using the direct expression or automatism of the Surrealists, the resulting canvases express the existential anguish wrought by war. Implicit political commentary becomes more overt in the works of Caniaris and Tàpies. Exhibited here are two works from the former’s Homage to the Walls of Athens, 1941–49 (a series he made in 1959); their ‘symbols’, dense layering and frottage technique viscerally evoking the walls of occupied Athens as rich palimpsests of political and social comment.

Homage to the walls of Athens (1959), Vlassis Caniaris. Courtesy Waddington Custot

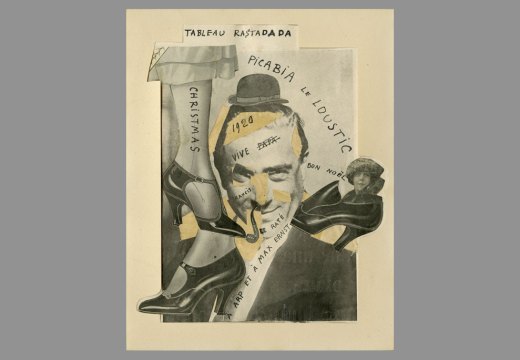

Tàpies recalled a youth spent holed up behind the medieval city walls of Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War. He wrote in 1969: ‘The dramatic sufferings of adults […] appeared to inscribe themselves on the walls around me.’ Citing archaeological publications, Leonardo notebooks, Brassaï and Dada, he continued: ‘These all contributed, not surprisingly, to the fact that my first works of 1945 already had something of the graffiti of the streets and a whole world of protest – repressed, clandestine, but full of life – a life of which was also to be found on the walls of my country.’

Dominating the gallery walls here are his monumental Duat (1994) and Aixeta/Tap (2003) – almost chunks of masonry themselves with their various encrustations, incisions, marks and symbols. The former refers not only to walls, but also windows and doors with its appropriated wooden shutters. The Twomblys could hardly prove a greater contrast in materiality. Here, the marks and scripts of the street are deconstructed and liberated to float free of the wall.

Duat (1994), Antoni Tàpies. Courtesy Waddington Custot

As Waddington Custot’s co-director Roxana Afshar comments: ‘A gallery space like ours offers a great opportunity to get under the surface of the works of art that we show and bring out specific histories of an individual piece. With the strong connections between the artists we selected – each of whom had been exposed to the work of the others in their lifetimes – we saw there was a story to tell about the everyday lived experience of people in the city which could be topical and current.’ Prices £1,200 to £1m.

‘Writings on the Wall’ is at Waddington Custot, London, until 30 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home