For a few moments, a few months ago, apps that could convert images taken on a phone or digital camera using intelligent filters into something resembling a Van Gogh or a Monet became briefly popular. Brushstroke, one such app, ‘transforms…album photos and snaps into beautiful paintings in one touch’. The app, that is, promises to impart a degree of tactility or granularity to the too-perfect products of digital photography – to return to the photograph something of the aura of the unmechanical artwork. You can even order prints on canvas. As a wonderfully argumentative exhibition at Tate Britain shows, however, a preoccupation with the interrelationship of the photograph and the painted image began at around the same time as photography itself; a fascination with the ways in which a photograph might become a painting and vice versa is braided into the history of both media.

H.R.H. Princess Alexandra, H.R.H. Princess Victoria & Mr. Savile, ‘Two’s company and three’s none’ in Tableaux Vivants Devonport (c. 1892–93). Wilson Centre for Photography

Two’s Company, Three’s None (c. 1892), Marcus Stone. Manchester Art Gallery

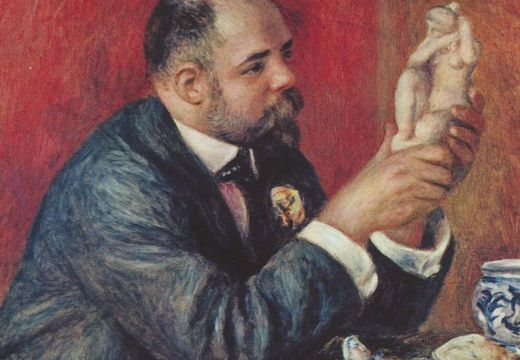

In the exhibition, somewhat inevitably, Ruskinian principles of inclusivity and accuracy are explored in the context of Pre-Raphaelite painting and photography. But repeatedly in ‘Painting with Light’ points of suture or contact, or gaps in memory, are emphasised, and these turn out to be the most interesting moments. Figures are often transposed from their original contexts – Princesses Alexandra and Victoria, and Mr Saville are moved out of doors and rendered anonymous by Marcus Stone in Two’s Company, Three’s None (1892). Only the props are real in Roger Fenton’s orientalist photographs, and the wires and backdrops are always visible. Ruskin’s famous watercolour, North-West Angle of the Façade of St Mark’s, Venice, turns out on close inspection to have been cut and pasted together and is, in this way, perhaps comparable in style to the ‘patchwork’ composition photographs of Oscar Rejlander, or Henry Peach Robinson and the members of the Linked Ring Brotherhood.

The Odor of Pomegranates (1899, published 1901), Zaida Ben-Yusuf. Tate

A number of compelling thematic echoes are developed in this exhibition: we can compare views of Edinburgh, visualisations of Tennyson’s poems, pictures of pomegranates. Throughout, however, the way painting remembers photography, and photography remembers painting, turns out to be as much a matter of style as of subject matter. If the accuracy and luminosity of Hunt and Millais draws upon the sharpness of the daguerreotype, the haze of Peter Henry Emerson’s photogravure The Bridge (1895) consciously recalls Whistler’s nocturnes. In Dew-Drenched Furze (1889–90), even Millais gives up on accuracy, moving instead towards abstraction – an aesthetic that can by this stage also be recognised as photographic.

The Woodman’s Daughter (1850–51). John Everett Millais. Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

In his famous essay on the photograph in The Salon of 1859, Baudelaire assigns photography to the scientist and the archivist, and reserves for the fine artist ‘the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary’. The operations of memory are a central preoccupation of ‘Painting with Light’. However, the emerging claim of the exhibition as a whole is that, if photography allows memory to be either artificially enhanced or mechanically externalised, the photograph also affords 19th- and early 20th-century artists an opportunity to make imaginative and even experimental use of memory as both a theme and technique.

Of course, photographs often functioned as aides-memoire – as with Holman Hunt’s View of Nazareth (1855/1860–61), begun on site and finished with the aid of James Graham’s Nazareth from the North (1855). Just as often, however, memory is reconfigured by photographs. This is the case in David Octavius Hill’s Disruption Portrait (1843–66). Hill’s enormous painting depicts the founding of the Free Church of Scotland. It was assembled piecemeal with the aid of hundreds of individual photographs taken by Hill’s partner Robert Adamson and their assistant Jessie Mann. In the resulting painting, each face stands out as clearly as every other. Forgoing emphasis and selection, Disruption Portrait operates as a pointedly democratic memorial, though its uncanny accuracy makes looking at it utterly unlike the normal experience of remembering. And this is perhaps the most forceful claim made by this exhibition: that one way of remembering the visual art of the 19th and early 20th century more truly is to re-examine the way these works themselves brought memory up to date.

‘Painting with Light: Art and Photography from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Modern Age’ is at Tate Britain until 25 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home