Some of the most notable examples of artistic production in the long history of Persian arts were created in the reign of the Qajar dynasty in the 19th century. While Persian arts are usually associated in the popular imagination with exquisite miniature paintings and carpets, or other luxury decorative arts, the arts of the Qajar period are characterised by large-scale works and the incorporation of new technologies. Twenty years ago ‘Royal Persian Paintings: the Qajar Epoch, 1785–1925’ at the Brooklyn Museum of Art introduced the dazzling and unfamiliar works of this period to the West. A number of exhibitions in France and the US are now renewing that interest. ‘The Rose Empire: Masterpieces of 19th-Century Persian Art’, a large survey of painting and decorative arts, is about to open at the Louvre-Lens (28 March–23 July). ‘The Prince and the Shah: Royal Portraits from Qajar Iran’ at the Freer | Sackler brings together paintings, photographs and lacquer-painted objects from the museum’s permanent collection (24 February–5 August). And at the Harvard Art Museums last year, ‘Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran’ offered new visual and intellectual juxtapositions of a range of splendid works from the era.

After the invasion of Afghan tribes in 1722 and the collapse of Safavid rule, the ensuing decades of political chaos and social fragmentation were brought to an end in 1785 by Aqa Muhammad Khan, chieftain of the Turkic Qajar tribe, whose tactical genius was matched by the shockingly brutal subjugation of his enemies. His assassination in 1797 was followed by two Qajar reigns in which a central government was established and Tehran’s position as the new capital became permanent. Under Fath ‘Ali Shah (r. 1797–1834), Iran’s Caucasian territories were ceded to Russia, thus realigning Iran’s borders to the outlines of the country we know today. The reign of Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848–96) was strengthened by the creation of new permanent armies, and institutions of higher learning based on modern technologies and inspired by European models. Qajar rule is usually understood as being tethered to its main ideological and political predecessor, the Safavid reign of 1501 to 1722, but also as a bridge to modernity – and this duality can be seen in the paintings of the period.

Fath ‘Ali Shah on his throne (c. 1800–06), attributed to Mihr ‘Ali. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: RMN-GP (Musée du Louvre)/Hervé Lewandowski

The long reign of Fath ‘Ali Shah provided Iran with relative political stability and a ruling Qajar elite (he fathered more than 100 children). In the life-size portrait that depicts him sitting on a gilded, enamelled and bejewelled throne chair, he arrests the viewer’s attention with his direct gaze, enormous beard, and extravagant royal paraphernalia. The painting, which was probably commissioned from the court artist Mihr ‘Ali in around 1800–06, was presented to the French envoy Amédée Jaubert in July 1806 as a royal gift for Napoleon (hence its current home at the Louvre). This is a state portrait intended to awe, with the Shah displaying the accoutrements of his authority not only in the elaborate throne but also with the massive Taj-i Kiyani crowning his head, the heavily and exquisitely bejewelled armbands, the belt with its long attachment associated with the Qajar tribal costume, and the sword of state.

Mural at the Chehel Sutan Palace in Isfahan, from the 16th century, showing the Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp receiving the exiled Mughal emperor Humayun Photo: © EmmePi Travel/Alamy Stock Photo

Several features of Fath ‘Ali Shah’s portrait strike a familiar historical chord while also signalling a new era in pictorial representations of authority and its sources of legitimacy. Compare it, for instance, with a large mural painting from the audience hall of the Chehel Sutun Palace (Palace of Forty Columns) in Isfahan, the Safavid capital from 1590 to 1722. Here Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–76) is dressed in a crimson-red robe worn over an embroidered gold shirt. He is also wearing a gem-encrusted belt from which his jewelled sword hangs and his turban is elegantly wrapped around a baton-like extension of a skull cap sporting gorgeous aigrettes. Tahmasp’s rank is made clear through his larger size relative to the other figures, his outward glance and his hand gesture. Although the Mughal Emperor Humayun is also luxuriously robed and turbaned according to his station, he is smaller in stature and more submissive, even suppliant, in his hand gestures. The Safavid Shah is the host of a deposed ruler – Humayun took refuge at the court of Tahmasp in 1544, while preparing to return to India to regain his throne. The Safavid murals at the Chehel Sutun Palace were composed principally around the theme of royal generosity and the extension of political refuge and support to deposed Mughal and Uzbek rulers.

The emphasis on the figure and on imperial regalia, stiff, frontal poses, commanding gestures and piercing gazes became defining characteristics of the portraits of Fath ‘Ali Shah, and apply to much Qajar royal portraiture. For the Qajars the Shah was the progenitor of a princely clan, and this relationship formed the administrative and imperial structure of Qajar rule. In the Safavid system, by contrast, the Shah’s authority derived from his role as the head of a royal household, which included the harem, where his mother might be of Circassian, Armenian or Georgian origin and not of Safavid royal blood, and a large administrative class of dignitaries and administrators, consisting of converted Circassians, Armenians and Georgians, as well as the eunuchs of the household. While the pictorial representations of the Safavid imperial household and the Qajar Shahs is quite different, the example of how the Safavids had conveyed their imperial authority in visual terms was not lost on Qajar designers, artists and planners.

Safavid Shahs were rarely portrayed on a physical throne and never wore crowns. Both objects were anathema to a system of rule in which the Shah stood as the representative on earth of the Shi‘i imams. The image of an enthroned and crowned king in the pictorial programmes of the Qajars was strengthened by the appropriation of pre-Islamic Iranian representations of kings – the monumental rock reliefs of the Sassanian kings (224–651), were particularly inspirational.

Fath ‘Ali Shah sitting on his throne from the Shahanshahnama of Fath ‘Ali Khan Saba (c. 1810–40), unknown artist. Musée du Louvre, Paris Photo: © RMN-GP (Musée du Louvre)/Raphaël Chipault

Continuities from the Safavid period are detectable in such Qajar images as a page from a manuscript of the Shahanshahnama (The Book of King of Kings). This was a poetic celebration from around 1810 of the reign of Fath ‘Ali Shah and a deliberate emulation of the great Iranian national epic of the Shahnama (The Book of Kings), composed by the poet Firdausi in 1010, and regularly copied and illustrated on commission from kings from the early 14th century onwards. Fath ‘Ali Shah’s grandiose claim to be the king of kings, in the tradition of the ancient Iranians, is conveyed by illustrations of him enthroned and surrounded by his courtiers, acting not in the traditional manner of the kings of the 11th-century epic poem, but as a contemporary all-powerful sovereign. These smaller images, made for books that could be transported, were designed as gifts and produced in multiples.

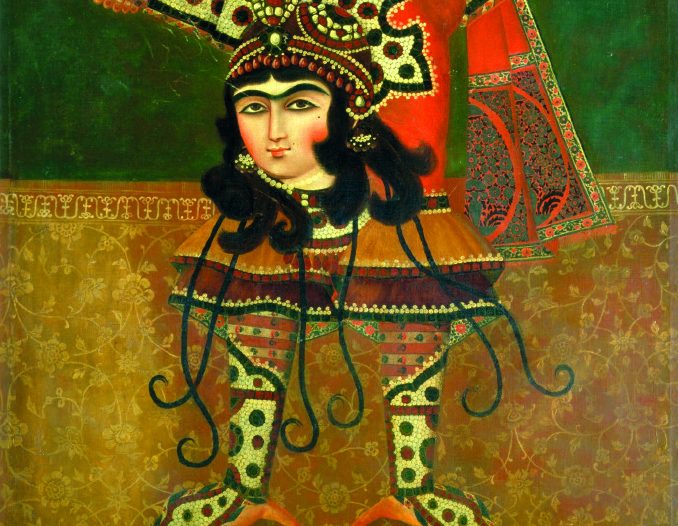

The Safavid mural at Chehel Sutun is also useful as a way of understanding how Qajar artists developed a repertoire of paintings specifically designed for interior architectural decoration. As had been the custom during Safavid rule, most of the artists worked in the court atelier. In earlier periods this institution was known as the kitabkhana (a library-cum-book production centre, including painters and calligraphers); in the Qajar period, it becomes the naqqashkhana (the house of painting), with a clear preference given to the art of painting. There are countless life-size paintings in oil on canvas, shaped to fit into niches in the interiors of special chambers in 19th-century palaces and mansions. In the paintings of ‘tumblers’, for example, girls stand on their hands or folded arms in impossible upside-down poses, with their heads nonchalantly turned to face the viewer, hennaed feet up in the air, puffy pantaloons and skirts and petticoats arranged in folds that completely conceal the body. While these acrobatics are uniquely Qajar, a familial connection with the dancing girls in the Safavid mural seems clear.

Female tumbler (c. 1800–30), unknown artist. Victoria and Albert Museum, London

It was in Isfahan that the Safavid penchant for large-scale figurative paintings, either directly applied to prepared walls (as in the Chehel Sutun case) or painted on canvas in oil pigments popularised a new style and form of painting. Mansions belonging to high-ranking ministers of the court and to wealthy Armenian merchants competed for the services of palace artists to create paintings such as the late Safavid portrait of an unknown, possibly European gentleman. From an iconographic point of view, a standing pose in a life-size image such as this should be understood as a predecessor of the standing images of Qajar kings. Clients commissioned a variety of portraits that were not necessarily of specific individuals, but representative of the types of men and women who were to be found in the cosmopolitan world of Isfahan. Georgian, Armenian, Russian, Spanish and other European portrait ‘types’, as well as Persians, graced the walls of the palaces and mansions alongside historical and literary subjects. The life-size figure types and large-scale thematic paintings in Safavid Isfahan inspired the presence throughout Qajar interiors in Tehran and elsewhere, of images of dancers, hunting scenes, and enthronement and court gatherings that can be found in museums and in some cases still in situ in Iran.

Portrait of a European Gentleman (17th century), unknown artist. Museum of Islamic Art, Doha. Photo: Marc Pelletreau; courtesy Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

In contrast with the grandeur of the portraits of Fath ‘Ali Shah, however, the degree of informality and verisimilitude with which later Qajar Shahs are depicted marks a decidedly modern turn in pictorial terms. The standing portrait of Nasir al-Din Shah propels the king to the foreground of the picture plane. The immediacy is heightened by the position of his hand resting on the back of a chair, and the casual way in which he extends one foot sideways while also leaning lightly on his sword. Looking at this portrait, the viewer can detect the new possibilities created by the introduction of photography in Iran, in the 1840s, soon after its invention in France. Jules Richard, a Frenchman, arrived in Tehran in 1844, bringing with him the first photographic camera and introduced daguerreotype technology. After his accession in 1848, Nasir al-Din Shah adopted photography as a serious pastime, taking photographs of his women, children and court eunuchs. Royal portraiture in the later Qajar period was deeply affected by the availability and widespread interest in photography; photographs would often serve as the model for portraits. Yet, it would be overstating it to assume these transformations were the result of increased European contact.

The extraordinary painting of Ladies around a Samovar (c. 1860–75) is a case in point. The artist Isma‘il Jalayir, a well-known court artist, used photographs of individual women to compose a gathering around what appears to be an afternoon tea in a garden. Several of the figures are recognisable from other paintings as well as reminiscent of late Safavid types (the musician to the far right, for instance). Jalayir’s composition, however, is deliberately defiant of the mimetic devices so central to photography, at least in its early uses. The women are posed tightly together on a porch (notice the column to the right) against a lush background of trees and bushes and engaged in the activities one might expect of a gathering of women at court: dancing, playing music, smoking, drinking tea, looking elegant in their finery. The painting is as innovative in style as Persian miniature paintings of the 16th century or the Safavid portraits of the king and his entourage. Yet the unreality of what might otherwise be a depiction of an everyday genre scene is unsettling and utterly modern. Nowhere do we find this kind of intermixing of styles and modes of picture-making in the painting traditions of Iran before the late 19th century.

Ladies around a Samovar (c. 1860–75), Isma‘il Jalayir. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Qajar portraits emerged from a distinctively Iranian understanding of portraiture in which creating a realistic depiction of the subject is less important than capturing an approximation of the sitter’s likeness. After the introduction of photography, the Persian way of making a portrait would perhaps be best described through the difference between a shabih-likeness and an aks, between a simulation of the image and an exact duplicate; a distinction that is made also in examples of Persian painting from the Safavid and Qajar periods. It is in this sense that Qajar portraiture assumes its place within the traditions of Persian painting and demonstrates its capacity to receive and refashion influences and styles to suit its own needs.

Sussan Babaie is the Andrew W. Mellon Reader in the Arts of Iran and Islam at the Courtauld Institute of Art.

‘The Rose Empire: Masterpieces of 19th-Century Persian Art’ is at the Louvre-Lens until 23rd July.

From the April issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home