The Smoking Girl (1940) isn’t looking at you: she has her mind on other things. You can pass time in the painting’s company but it won’t be spent locked into a cryptic exchange of gazes. Her eyes won’t follow you around the room. If you are going to hang out with Smoking Girl it will be on a different footing. There is a sense of expectant potential, perhaps, because the girl is still drawing on the cigarette. She hasn’t exhaled yet; when she does, she might say something. Perhaps it will be clever, or funny, or inconsequential as smoke. It’s a painting about friendship because it’s a painting that’s open to friendship. And it is the self-portrait of an artist and writer whose great subjects were love and freedom, and how to love while remaining free: that is to say, the art of friendship.

The Smoking Girl (Self-Portrait) (1940), Tove Jansson. Photo: Finnish National Gallery/Yehia Eweis; © Moomin Characters

The bright colours of the canvas owe something to Matisse and something to Van Gogh: the girl is clad in gold on a ground of blue, like a medieval Virgin in reverse – and with all that might entail. The artist, Tove Jansson (1914–2001), was a great colourist who lived a richly plural life. Born into Finland’s Swedish-speaking minority to a Swedish mother and a Finnish father, both artists, she grew up on both sides of the Baltic. Jansson trained as a painter and illustrator in Stockholm and Paris, and made an early living through commissions and piecework. She was an acerbic and witty anti-fascist cartoonist during the Second World War, sending up Hitler and Stalin in covers for the Swedish-language periodical Garm. Descended on the one hand from a famous preacher, and on the other from a pioneer of the Girl Guide movement, she was raised on the Bible and on tales of adventure (Tarzan, Jules Verne, Edgar Allen Poe). In her thirties she built a log cabin on an island and was a capable sailor. She lived visibly and courageously with her partner, the Finnish artist Tuulikki Pietilä, at a time when lesbian relationships did not enjoy public acceptance. She considered emigrating at various times to Tonga and Morocco but, despite travelling widely, remained rooted in Finland where she became (dread accolade) a ‘national treasure’. She wrote a picture book for children about the imminent end of the world and spare, tender fiction for adults about love and family. She never stopped drawing and painting. She was Big in Japan.

And, of course, she invented the Moomins, a family of white, forest-dwelling, big-snouted trolls, whose stories she told and illustrated in children’s novels, comic strips, plays, picture-books, and an opera. This is worth putting last, however, not because it was the least of her achievements but because in her international reputation it has come to eclipse everything else. In fact the Moomins were close to the heart of who she was: the earliest troll doodles were used as thumbnail self-portraits, a way of signing cartoons, canvases, or frescoes; and she wrote herself and her circle into the books’ cast of characters. Yet the Moomins are understood in the fullest sense only in the context of her wider creative life. This is a view that has sometimes been hard to get, but which the major touring retrospective of Jansson coming this autumn to Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, promises to offer (25 October–28 January 2018).

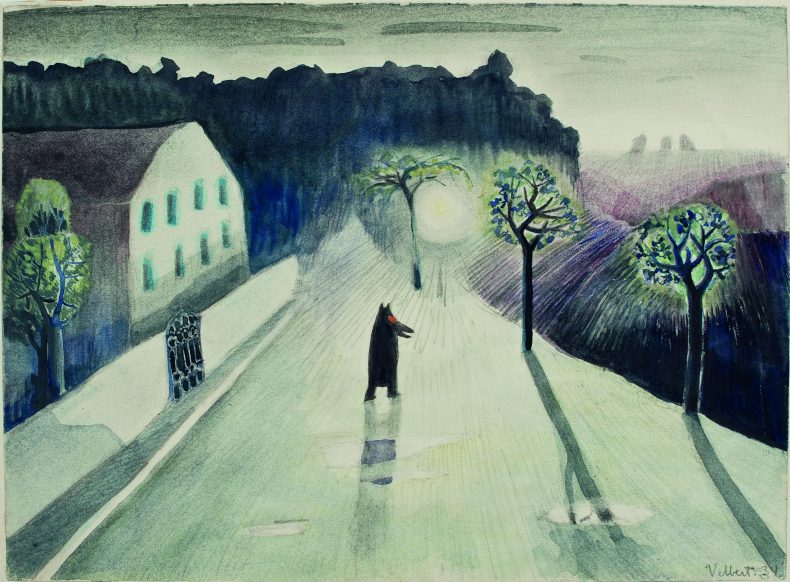

A Black Moomintroll Walks around Town (1934), Tove Jansson. Moomin Museum, Tampere; © Moomin Characters

In the earliest paintings to feature Moomins, the creatures are often ambivalent, eerie presences. A Black Moomintroll Walks around Town (1934), for example, sets a recognisably Moomin-like creature in silhouette against a white street. This looks like the deep Finnish winter; the reflections suggest a surface slick with ice. Armless and tailless, ramrod-straight, this might almost be a Lowry stick-figure heading home out of the factory gates. Against an outcrop of rock as fantastic as the far distance of a Renaissance painting, the Moomintroll slopes back towards the dark. If you have known Tove Jansson’s work from childhood, your first glance at this picture might carry a simultaneous shock of strangeness and familiarity, like seeing the face of Bugs Bunny lifted out of those concentric circles in the Loony Tunes intro and superimposed on to Munch’s The Scream. Different artistic styles are blended, and so are different worlds: uprooted from the pastoral Moominvalley, this troll is marooned in a hinterland between fantasy and symbolism, fairytale and nightmare.

Watercolours like this one predate the children’s books, and so seem to offer a missing link between Jansson’s stories and their deeper roots – in the author’s private mythology, in the worlds of surrealism and expressionism (there are shades of Alfred Kubin), in the unfolding of historical events (Jansson painted the Black Moomintroll during a visit to Germany shortly after Hitler’s rise to power) and in a Nordic folk tradition of trolls and forests, light and dark. But then, of course, these feelings are blended into the Moomin stories, too: in the terrible threat of Comet in Moominland; the silent, electric Hattifatteners and icy, malevolent Groke of Finn Family Moomintroll; and the vast snowy forest of Moominland Midwinter. Perhaps what’s really troubling about these early Moomin pictures is their loneliness: that whereas the books always pivot on family and friendship, on the need for solitude and the need for company, these lost Moomintrolls have tipped over from solitude into loneliness and are trapped there.

Jansson understood that the shivers of cold and fear which run through the Moomin books are also shivers of pleasure. The phrase is her own, from a letter of February 1965 to Åke Runnquist of the Swedish publishing firm Bonniers: ‘The story is terrifying and can in no way be seen as an idyll, but it causes shivers of pleasure.’ She is writing, not about her own books, but about Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which she had just agreed to illustrate in a new Swedish translation by Runnquist himself. Jansson had already illustrated Runnquist’s translation (with Lars Forssell) of The Hunting of the Snark (1959), and an edition of Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1962), and Alice was an irresistible next step. By this time she was increasingly famous and successful, no longer taking on jobs to pay the bills, and her late projects as illustrator were freely chosen labours of love, revealing something about her artistic and literary affinities. Put differently, they represent another – complex, distant – kind of friendship.

They make curious friends, of course: Carroll, the fastidious, orderly, obsessive, hyper-logical mathematician of Christ Church, Oxford; and Jansson, the bohemian, quizzical, adventurous, outdoorsy painter of the Finnish archipelago. Yet their lives touch in significant places. Both were deeply invested in the speculative imagination and spoke about their writing in terms of ‘fairy tales’. Both were collectors, instinctual homebuilders, natural hobbyists. Both looked at the quirks and calamities of their historical moment from the position of outsiders, albeit of very different kinds. Both were childless, and explored through their work complex, self-defining relationships to childhood. Recently reprinted in English (Tate Publishing), the Jansson edition of Alice brings her own imagination and Carroll’s into a revealing kind of counterpoint, allowing new perspectives into each of them.

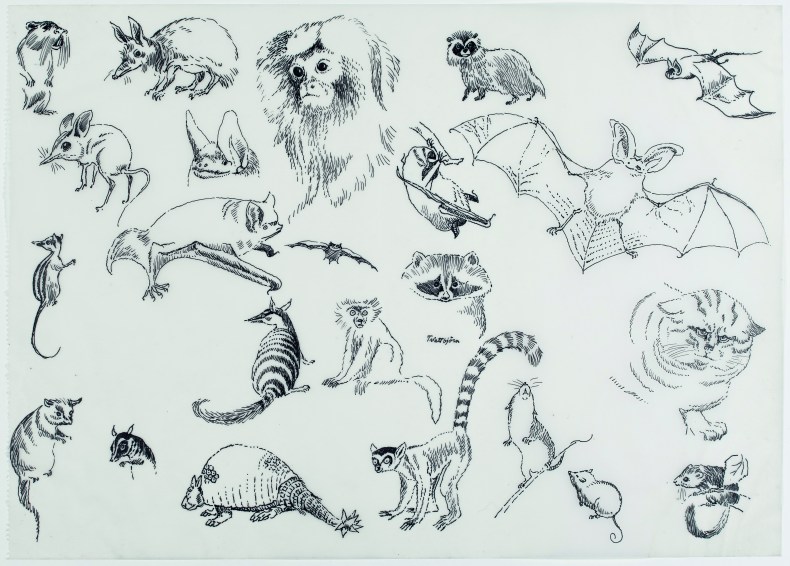

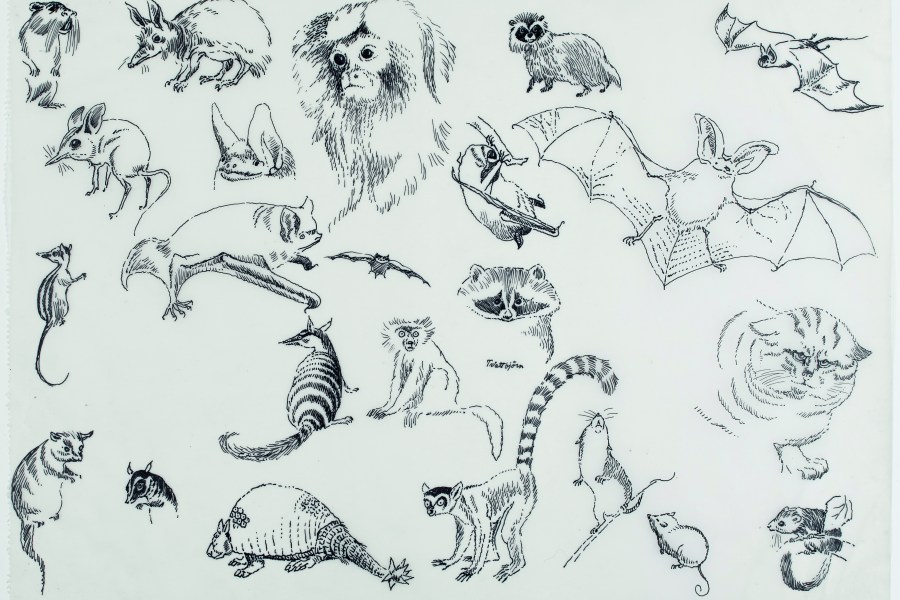

Preliminary sketches for Alice i Underlandet (1966), Tove Jansson. Tampere Art Museum; © Tove Jansson

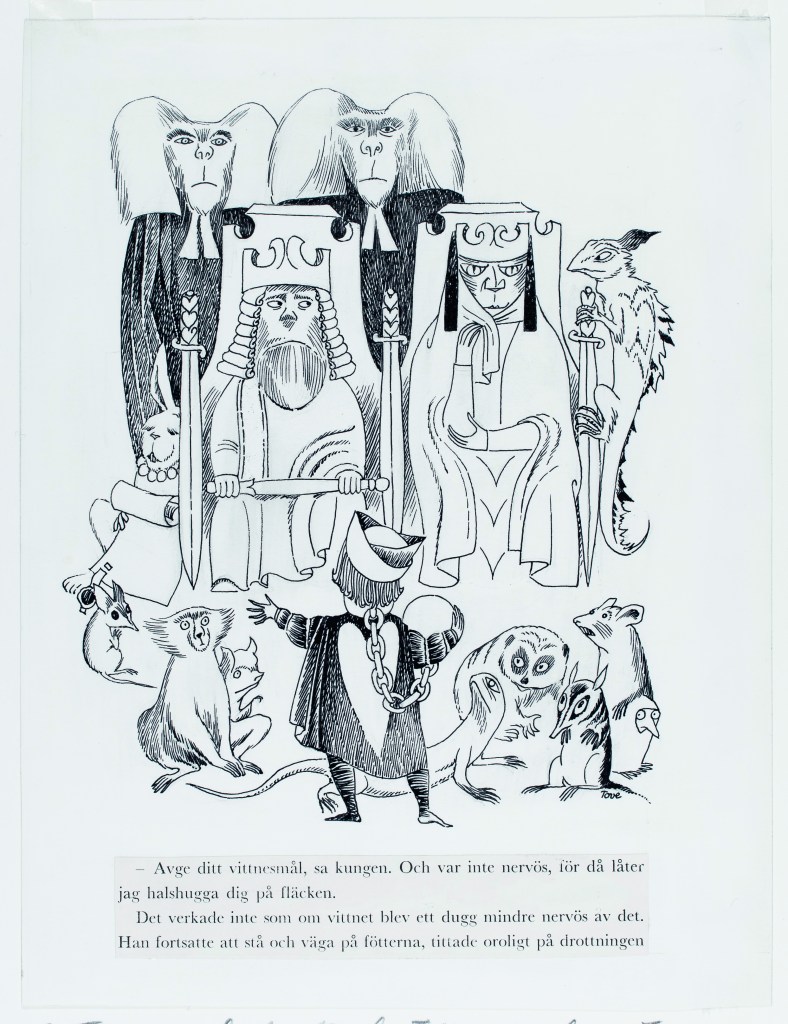

In Swedish, Alice in Wonderland becomes Alice i Underlandet, ‘in the wonder/under-land’ (the word under having both meanings). It’s a pun Carroll would have used if he could to send his heroine down the rabbit-hole (his initial title was ‘Alice’s Adventures Underground’), and looking through Jansson’s eyes we are reminded that this book takes its heroine deep down into a non-human world. Preliminary sketches for Alice, on display in the Dulwich exhibition, reveal Jansson collecting and practicing thumbnails of animals, recognisable kin of the ‘small beasts’ that are the supporting cast of the Moomin stories, with which she would populate the trial scene in the final two chapters of the book. In the edition of Alice illustrated by Jansson, a host of Moominvalley-ish creatures, curiouser and curiouser, proliferate alongside the text, like the odd mushroom-shaped creatures capering around Alice’s recitation of ‘You are old, Father William’ which do not so much illustrate the poem as use it for a jumping-off place for another, equally opaque, story to be filled in by the reader’s imagination. (The doodler was always an important aspect of Jansson’s identity as an artist: the first Snork, a close relation of the Moomins, was drawn on a toilet door. She is recognisably an ancestor of medieval scribes filling manuscript margins with jokes.)

To be friends with Carroll is not, for Jansson, a matter of bending herself into a new shape to fit around him, but of being fully herself in response to him. This distinction was one that she guarded fiercely. In 1941 Jansson wrote to her friend Eva Konikoff about her aversion to marriage: ‘Of course I’m sorry for [men] and of course I like them, but I’ve no intention of devoting my whole life to a performance I’ve seen through. I see how Faffan [her father], the most helpless and instinctive of men, tyrannises over us all, how Ham [her mother] is unhappy because she has always said yes, smoothed over problems, given in and sacrificed her life […]’. This patriarchal pattern for marriage, one Jansson decisively rejected for herself, is written with surprising affection into the Moomin books in the persons of the self-absorbed, romantic Moominpappa and the self-sacrificing, pragmatic Moominmamma. And as an illustrator, too, Jansson was not in the business of making images that would be the text’s helpmeet or handmaiden, but which keep it company on their own terms.

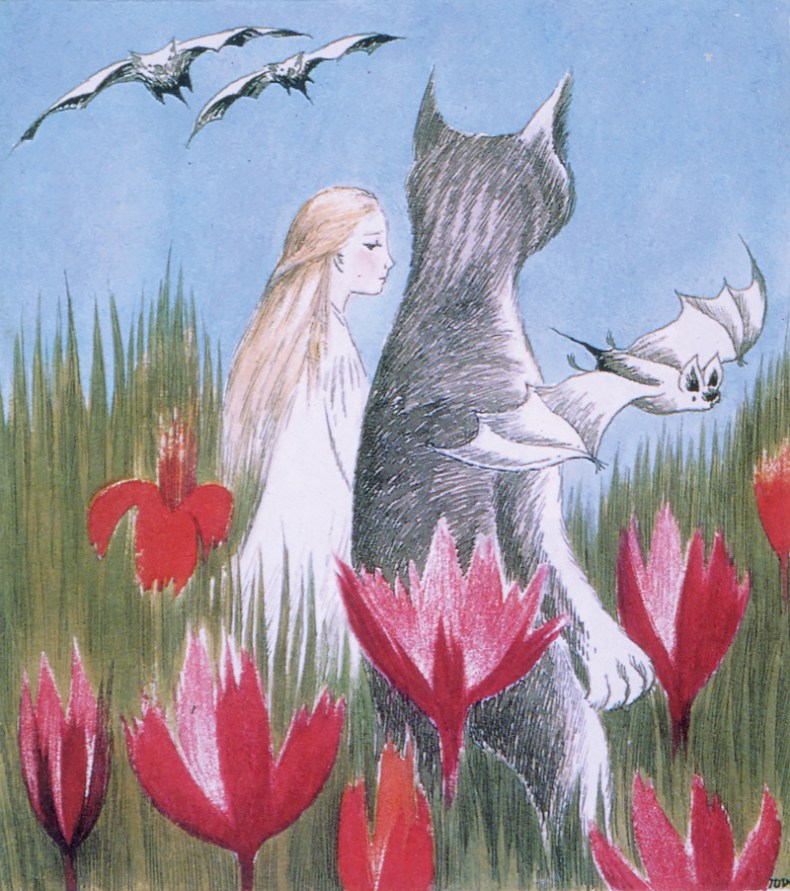

Colour illustration of Alice and Dinah for Alice i Underlandet (Alice in Wonderland; Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1966), Lewis Carroll, trans. Åke Runnquist with illustrations by Tove Jansson. © Tove Jansson

The most companionable image in Jansson’s Alice is also one of its most troubling and inscrutable: the full-colour plate of Alice walking hand in hand with Dinah, her cat. It owes something to the Technicolor grandeur of the field of poppies in the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz, in which Dorothy and her friends are put to sleep, even though in Kansas Dorothy is already asleep, or unconscious. In Carroll’s story too this scene is a dream within a dream: falling down the rabbit-hole, Alice ‘has just begun to dream that she was walking hand in hand with Dinah, and saying to her very earnestly: “Now, Dinah, tell me the truth: did you ever eat a bat?”’ The critic Nina Auerbach noticed how Alice’s ‘persistent allusions to her predatory cat, Dinah’ seep into a wider anxiety about eating and being eaten that runs through the text, and Jansson places Dinah in the foreground slightly looming over Alice, her large and threatening paw picked out in a patch of light. But less threatening to Alice, perhaps, than to the bats who swoop low across the field: Alice has just asked Dinah to confess whether she ever ate a bat. Dinah, after all, is also Alice’s only friend, or at least the only friend she mentions without apparent rivalry or suspicion. And as both Auerbach and William Empson observed, the only figure in the book to whom Alice refers as her ‘friend’ is the Cheshire Cat, Dinah’s Wonderland counterpart. Jansson’s illustration catches these mixed feelings in a strange, sad moment of silent togetherness. By showing us a scene that Alice only glimpses fleetingly, she catches something in the penumbra of Carroll’s narrative: a friendship inflected with loneliness, a glimpse of longed-for companionship in a book in which almost nobody treats Alice companionably.

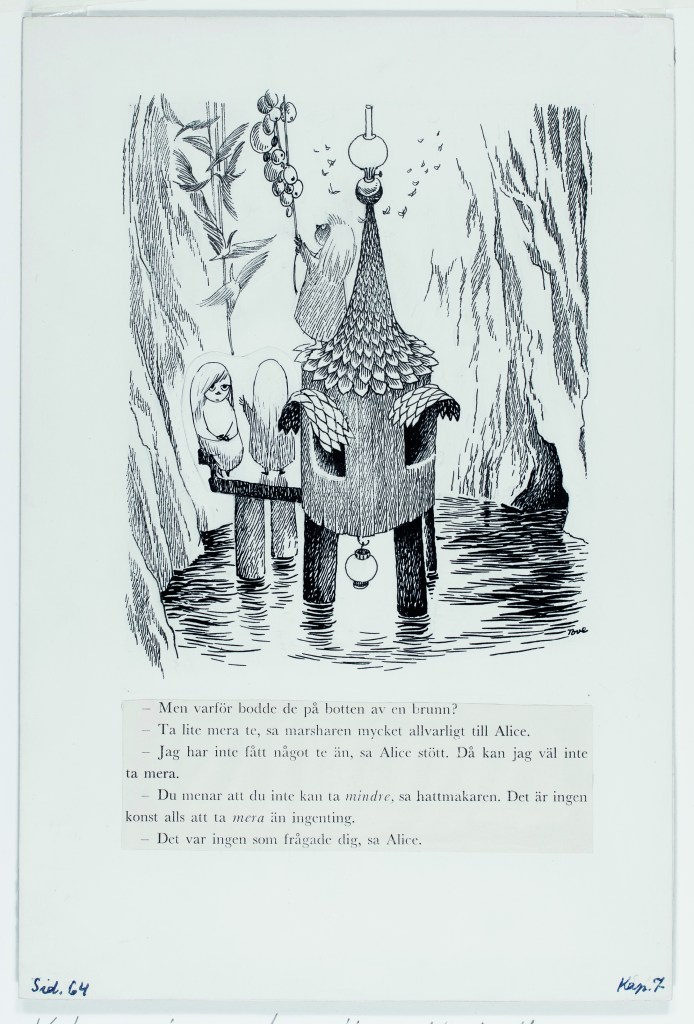

Illustration of the treacle well for Alice i Underlandet (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1966), Lewis Carroll, trans. Åke Runnquist with illustrations by Tove Jansson. © Tove Jansson

Jansson knew that she was creating a new partnership for a story that had been a double-act from the start. Despite the work of multiple illustrators over the years, Alice has always been inseparable, for English-speaking readers, from John Tenniel’s illustrations that accompanied the book’s first edition. Jansson’s biographer Boel Westin points out that ‘Lewis Carroll has never been a major figure in Sweden’, and this was surely a liberation for an illustrator seeking to make friends anew with the text. Nonetheless Jansson was also astute in seeking out subjects, like Alice’s walk with Dinah, that Tenniel never attempted and were thus unclaimed territory. One of her finest pictures shows the three little girls, ‘Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie’, about whom the Dormouse tells his story during the famous Mad Tea-Party. They lived in a treacle-well, the Dormouse says, and drew ‘all manner of things – everything that begins with an M […] such as mouse-traps, and the moon, and memory, and muchness – you know you say things are “much of a muchness” – did you ever see such a thing as a drawing of a muchness?’ In response to which, Jansson, who also liked to draw things beginning with an M – Moomintrolls, and Mymbles, and Little My – creates wonderful flights of birds and balloons, a lamp buzzing with moths and other insects, a muchness that is wholly her own.

It is the odd glimpses of things on the periphery of Lewis Carroll’s vision that catch Jansson’s attention. The hallway where Alice weeps an ocean of tears, for example, is ‘lit with a row of lamps hanging from the roof’ – the kind of throwaway detail in Alice that, even more than the trial scene, anticipates the nightmarish quality of Kafka’s The Trial. Tenniel overlooked them entirely; but Jansson makes these lamps prominent and hypnotising, illuminating what she saw as the book’s sense of terror, and offering, at the same time, a ‘shiver of pleasure’. Something of their chilling light gathers around the lamp on top of the house in the three little girls’ treacle well too, and here the shiver of pleasure is also one of recognition, as this is unmistakeably modelled after the Moominhouse of Jansson’s stories. In many places in her Alice illustrations, there is the uncanny sense that in creating a visual frame for one of England’s most canonical children’s stories Jansson has found herself, to her own surprise, coming home again.

Illustration of the trial scene for Alice i Underlandet (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland; Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1966), Lewis Carroll, trans. Åke Runnquist with illustrations by Tove Jansson. © Tove Jansson

A nice instance of this is in the depiction of the King and Queen of Hearts, whom Jansson models unmistakeably after pieces from the Lewis Chessmen in the British Museum. From the position of the Queen’s arms and the ridges of the King’s beard they can be identified to a high degree of precision with specific pieces from the set. Jansson might have copied these images from catalogues or studies, but could just as well have seen them for herself. She visited London twice in the spring of 1954, for two whirligig weeks of meetings with publishers and admirers, ‘restaurants, excursions, masses of people and strong drink and theatre in the evenings’; in the midst of it all these Norse chessmen, found in what is now Scotland along a trade route with the British Isles, might well have made Jansson feel a strange connection with her Nordic home. Jansson was culturally and linguistically Scandinavian: the Swedish-Finnish culture into which she was born was the result of centuries of trade and conquest reaching out into the eastern Baltic, which was in many ways the looking-glass image of the extended Viking world to the west.

It remains a pity that Jansson never completed the Alice books by illustrating Through the Looking Glass (what might she have done, for example, with her namesakes the ‘slithy toves’?) And yet in a subtle, implicit way her mind was moving there already, by bringing the chess pieces of Looking Glass into Wonderland as models for the royal playing cards. It is a nod to Lewis Carroll, a silent expression of familiarity and friendship, but it may acknowledge other forms of friendship and sociability, too.

Family (1942), Tove Jansson. © Tove Jansson

The motif of the chess game harks back with strange poignancy to her group portrait Family (1942). Jansson’s younger brother Lars plays chess with the eldest brother, Per Olov, then enlisted in the Finnish army, while their mother ‘Ham’ (the graphic artist Signe Hammarsten-Jansson) looks on anxiously, and her father ‘Faffan’ (the sculptor Viktor Jansson) stares distractedly into the distance. In the centre is Tove, looking down protectively towards Ham and Lars, but dressed for outdoors. Is she taking her gloves off, or putting them on? Is she glancing back at them before stepping through that open door, or has she stepped back in? What bonds, what gravitational forces keep families together? The women are on guard, the men at ease, or merely lost: each member of the group radiates intense privacy in a space that affords them almost none. It is a group of lonely people being sociable together, or perhaps sociable people being lonely together. There is love here, but love contained and constrained, struggling to grow into something liberated and egalitarian. That was something for which she needed art and imagination, and even the licence of nonsense.

‘Tove Jansson (1914–2001)’ is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, from 25 October until 28 January 2018.

From the October 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home