Tim Etchells and Vlatka Horvat are artists and curators after my own heart. Walking into their current exhibition ‘What can be seen’ at the Millennium Gallery in Sheffield, I get my usual thrill at entering a museum store. They have turned the exhibition space into a homage to museum processes, bringing a playful eye to the recording, store and care that is at the heart of curatorial practice, opening connections across the disparate collections of Sheffield Museums.

We meet in the café. The museum is bustling on a Saturday, and Horvat tells me how pleased they have been at the cross-section of unexpected audiences to the show. The Millennium Gallery is designed to be at the heart of the city, opening into the popular Winter Gardens. It is free and active and draws in a different crowd from their usual, the sort who purposely choose to visit a contemporary art show. These artists could not be better advocates for free entry and opening up collections.

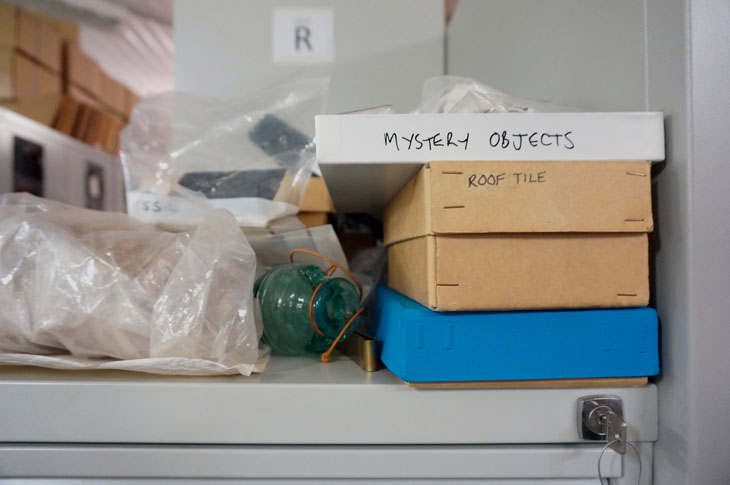

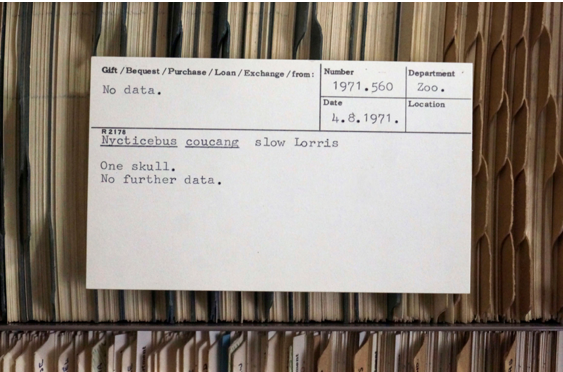

From the series ‘No Contextural Information’ (2017), Tim Etchells & Vlatka Horvat. Courtesy the artists

They have spent two years looking at the collections in Sheffield, working with curators from across archaeology, natural sciences, decorative art, visual art, social history, and the Ruskin collection. They have clearly become infatuated with the stores and the practices that take place there, fascinated by the ephemeral and quotidian materials produced by curators labelling, packing and recording the collection. Etchells explains: ‘It’s a very interesting thing to see the collection in storage. They’re not in a display case. You get to see them not as exhibits but as objects, closer to how they were in the world. They become banal but also fascinating, they have an everyday feeling.’

The result is an exhibition that ‘creates a portrait of a place and its processes’ as Horvat puts it, that ‘makes people look again, and look in a different way’ for Etchells. They have achieved this in three ways. Firstly, drawn to the categorisation, repetitive practices and profusion of many museum collections, they have selected series of related objects. Pocket watches appear in their boxes and tissue paper straight from the store, a collection of taxidermy barn owls peer down from a shelf, a mass of aerial photographs show the path of the M1 motorway.

Secondly, they have created a long modern wunderkammer, drawing diverse objects from across the collections based on affinities like shape, appearance or texture. A forlorn looking teddy bear lies next to a disconcertingly happy pufferfish; a series of spherical shapes range from knitted training breasts to boules to muffineers for shaking sugar. While the effect is visual and playful, Etchells and Horvat have also ensured that people can identify objects and learn about the collections. While I was viewing the case, groups around me were poring over the handlists of the objects, guessing, identifying and discussing: the exemplary curious visitors to a cabinet of curiosity.

Lastly, they have created two new series of photographs in response to the museum stores. No Contextual Information and Card Index (Details) pull out whimsical, beguiling annotations and record cards, bringing curatorial work into focus. Boxes are labeled, relocated objects are noted, material fragility is advertised, and questionable identification is raised. ‘Starling?’ written on a post-it note attached to the case of a confused looking taxidermy bird was perhaps my favourite. These scribbles, corrections and attempts to instill order into a disparate collection show ‘a glimpse of somebody’s care, passion and commitment, and just not letting go’ enthuses Horvat, ‘in the items on show, but also in the museum as a structure, and the lives of a curator. It’s a compelling thing to put that on display.’

I end by asking them which object is their favourite, a mean question that they both take some time over. Horvat answers first, that hers is the selection of lantern slides meticulously created by Henry Clifton Sorby. Each contains not an image, but an actual natural specimen carefully squashed, representing for Horvat that ‘gesture of relentlessly having a go at the same thing over time’ which appears throughout the exhibition. Etchells’ choice is also exemplary in being an object not in the exhibition at all, one of the many that they were forced to reject. It is a handwritten journal describing the weather, kept to accompany the daily weather records from the meteorological station (which are on display) established by Elijah Howarth, curator at Weston Park Museum from 1876 to 1928. Etchells is drawn to this effort of observation, decade after decade, ‘this human act of paying attention’.

I end by asking them which object is their favourite, a mean question that they both take some time over. Horvat answers first, that hers is the selection of lantern slides meticulously created by Henry Clifton Sorby. Each contains not an image, but an actual natural specimen carefully squashed, representing for Horvat that ‘gesture of relentlessly having a go at the same thing over time’ which appears throughout the exhibition. Etchells’ choice is also exemplary in being an object not in the exhibition at all, one of the many that they were forced to reject. It is a handwritten journal describing the weather, kept to accompany the daily weather records from the meteorological station (which are on display) established by Elijah Howarth, curator at Weston Park Museum from 1876 to 1928. Etchells is drawn to this effort of observation, decade after decade, ‘this human act of paying attention’.

But both are also drawn to the platypus specimen. Mounted on a board, the platypus is displayed towards one end of their wunderkammer. Its appeal is in its object number ‘A1’ denoting that it was the very first object to be acquired into the Sheffield collections. I ask Etchells and Horvat what might come next for them, and they light up with enthusiasm at the unexplored avenues that this project had to leave behind. They’d like to make an exhibition that brings together all the ‘A1s’ from collections across the country. I really hope they do.

‘Tim Etchells & Vlatka Horvat: What Can Be Seen’ is at the Millenium Gallery, Museums Sheffield, until 7 May.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home