You must close the door behind you as you enter the Iannis Xenakis survey at EMST in Athens, in order to truly savour the onslaught within. Wherever you move, you are assailed by screeches, wails, blasts, parps, groans, snaps, crackles and pops, as a selection from the life’s work of this avant-garde composer is played over the speakers. It might be thought odd for an art museum to be hosting an exhibition of a musician, and this is not a blockbuster pop-culture show such as the V&A might put on, but Xenakis’s work stretches well beyond the sounds he made. An exhibition in 2022 at the Musée de la musique in Paris focused more on his primary career, but a rehang of much of the same material in Athens allows for a wider view of the works.

Iannis Xenakis and Le Corbusier departing for Brussels in 1958. Photo: SABENA press and information agency; © Collection Xenakis family DR

The life of Xenakis (1922–2001) is an amazing 20th-century tale. Born in Romania to a Greek merchant, he was studying engineering in Athens when he was caught up in the last days of the Second World War. A communist partisan, he lost his left eye to a British mortar shell and was forced to flee the country, ending up in Paris, where he fortuitously found work in the atelier of Le Corbusier. He became indispensable to the master, and while there he contributed to a number of the most significant buildings of the 20th century, such as the monastery at La Tourette. Meanwhile, he was indulging his passion for music by taking evening classes with Olivier Messiaen, and at the end of the 1950s he gave up the day job and became a full-time composer.

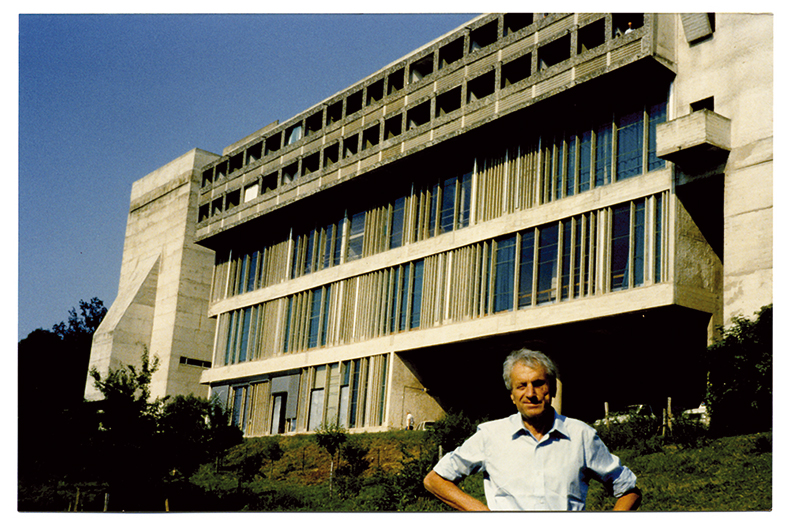

Iannis Xenakis in front of the monastery of Sainte-Marie de La Tourette. Photo: © Collection Xenakis family

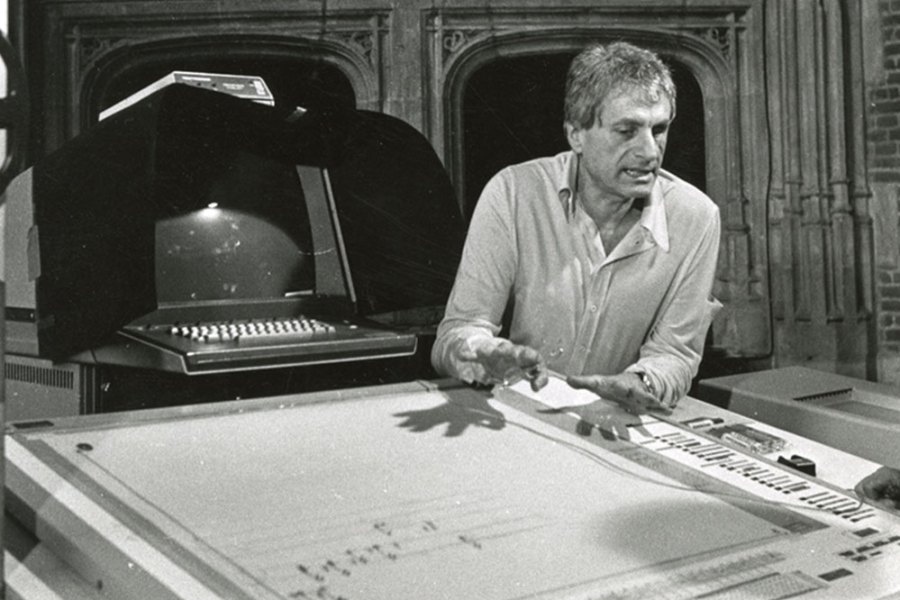

Xenakis’s prime contribution to music was to introduce a wide variety of compositional techniques derived from mathematics. The ‘serialist’ approach that had been developed by Schoenberg was, to Xenakis, not nearly rigorous enough. Over his career, Xenakis used stochastic analysis (the modelling of processes that appear random), probability theory, game theory, group theory, geometry and more, as well as developing new computer technologies to generate his compositions. They tend to be noisy, dissonant and incredibly difficult to play, featuring a wide variety of extended techniques, such as his trademark swooping glissandi, that nobody had ever heard before.

Part of the fun of engaging with this polymath’s output is seeing the same idea in a variety of contexts. For example, Xenakis essentially designed the Philips Pavilion for the 1958 Brussels Exposition, a once-neglected Le Corbusier building that now sits proud in the oeuvre, prefiguring as it does the more formally expressive architecture of the 21st century. This was a temporary concrete tent made up of odd curved surfaces, in which a light and sound show by Le Corbusier and Edgar Varèse was broadcast regularly. A large model of the pavilion, at a scale of 1:20, sits at the centre of the exhibition space, its form appearing to shift from every angle.

The Philips Pavilion at the Brussels Expo of 1958. Photo: © Koninklijke Philips N.V/Philips Company Archives

Around the same time as he was working on the Philips Pavilion, Xenakis was composing his breakthrough piece Metastaseis (1953–54), which features an incredibly memorable – and at the time shocking – opening, as a string orchestra hold one note only for it to gradually spread out to a chord of more than 40 separate dissonant parts. This process is essentially the equivalent of the paraboloid walls of the Philips Pavilion, and Xenakis’s diagrams drawn on mathematical graph paper are here in the show, right next to the first page of the score, which, along with the piece being heard through the speakers, means that we’re offered the same idea in no fewer than four different mediums.

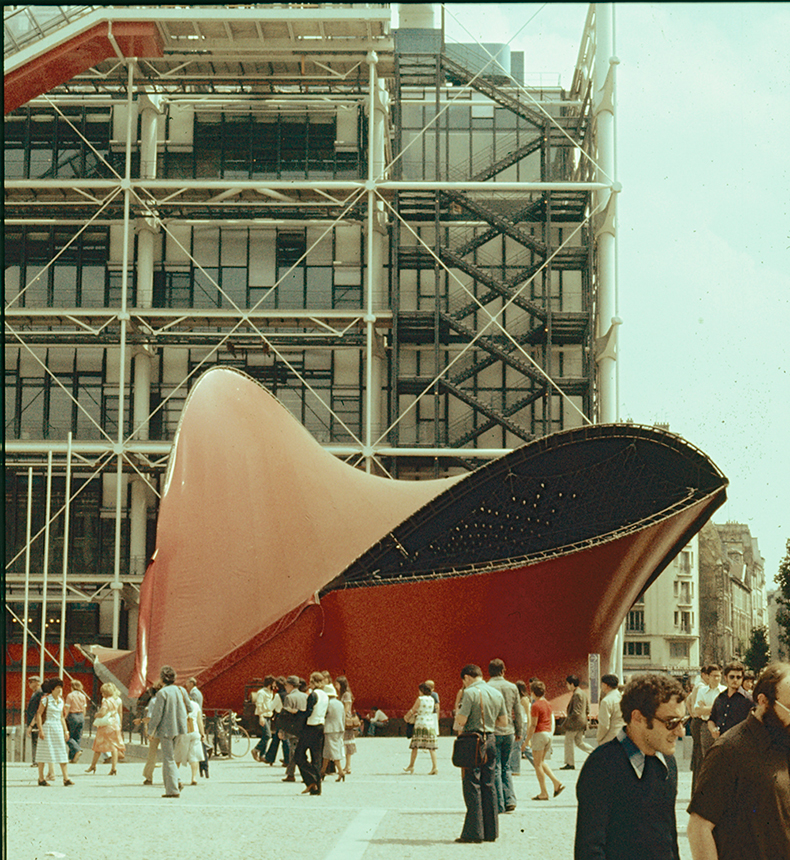

Xenakis lived a career of residencies, commissions and festivals, making the most of a Cold-War era when the avant-garde was more widely supported. His most ambitious projects were the Polytopes, multimedia spectacles that fused music, light and architecture, often taking place in dramatic historic locations like Persepolis or Cluny. This highlights another aspect of Xenakis’s work – a passion for ancient culture, particularly Greek, that ran through all his creations, no matter how high-tech or futuristic, from the names of his works to his regular habit of setting fragments of ancient poetry. One high point of his career was the Diatope (1978), a temporary commission for the plaza of the newly opened Centre Pompidou, where a laser show and electroacoustic work were broadcast within another swirling parabolic pavilion, a Gesamtkunstwerk visited by tens of thousands.

Diatope (Beaubourg Polytope) (1978), Iannis Xenakis. Photo: Pascal Dusapin

Upstairs, a supplementary show titled ‘Xenakis and Greece’ endeavours to explain Xenakis’s relationship to Greece for a younger generation of gallery visitors – despite not being able to return, on pain of death, until the fall of the Junta in 1974, his vision of a Greek identity in tune with its ancient past but looking straight ahead to the future helped make him a significant figure in Greek cultural life, if not exactly a household name. And while it’s challenging work, for sure, this show really manages to look beyond the po-faced ultra-modernist to see someone whose work connected to installation art, the counterculture, ecology and other more cosmic concerns, an old-school 20th-century utopian of the best sort.

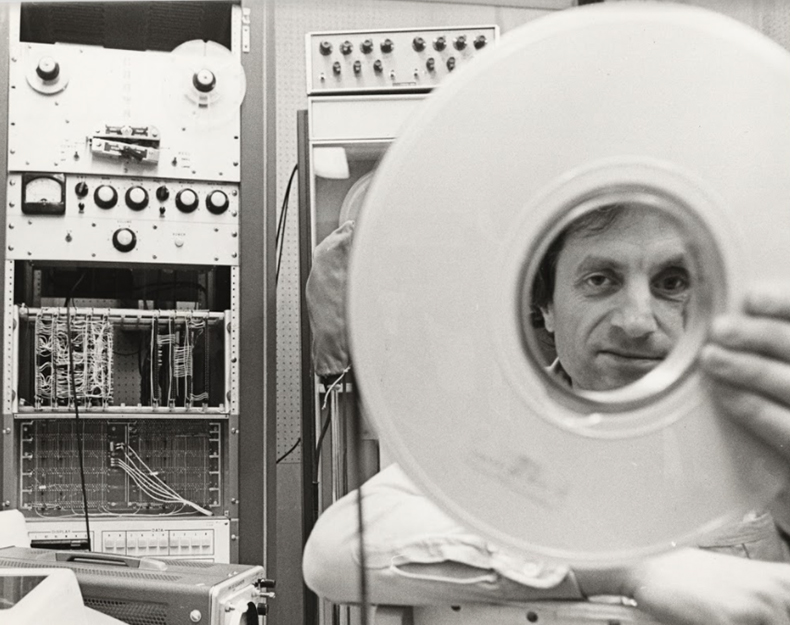

Iannis Xenakis at the University of Indiana in 1972. © Collection Xenakis family

‘Iannis Xenakis: Sonic Odysseys’ and ‘Xenakis and Greece’ are at EMST, Athens, until 7 January 2024.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home