From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Eugène Boudin’s Sunset over the Sea (c. 1860– 70) is one of three eye-catching pastels at the start of this exhibition. They can be identified with the late 1860s, a moment when there were many more artists striving to find new ways of making art than those who later showed as a group, from 1874 to 1886, in a series of eight Impressionist exhibitions. Boudin’s strong colours on buff paper, his black clouds and rough abrasive manner are surprising for an artist who encouraged the young Monet but did not himself become an Impressionist. Bolder still is the assured vigour with which Armand Guillaumin, in Sky Study (1869), builds up a sense of space, air and mounting clouds. Then there is Edgar Degas’s Beach at Low Tide (1869), its stilling emptiness permitting only minimal inflection in the movement of the waves. Three very different artistic personalities lie behind these works, but what unifies them is the search, not so much for the facts of landscape, but for the sensations it arouses.

The Fortifications of Paris with Houses (1887), Vincent Van Gogh. Photo: Michael Pollard; © The Whitworth, the University of Manchester

Sensations abound in Impressionist paintings – which is partly what makes it one of the most liberating and far-reaching movements in the history of art. It has been the case for many years now that, if a major Impressionist painting is consigned to auction, it usually attracts a new record price. A great deal of attention has been given to the graphic work of Van Gogh and to Cézanne’s watercolours. But group exhibitions of Impressionists’ drawings have rarely been mounted – and certainly not with the same attention to diversity and detail as here. This, after all, is a breakthrough period in France, when artists rejected hide-bound procedures, traditional teaching and restrictions set by the state. The Impressionists found the Salon irrelevant and turned away from the repeated use of specific subjects based on historical, mythological or religious matter. Instead, they were interested in modern life.

All this gave rise to new and challenging ways of making images, some of which anticipated future developments in modern art. It also bred a more relaxed approach, as can been seen in Degas’s illustration of 1876–77 for a satirical short story, ‘La Famille Cardinal’, written by his friend, the writer and librettist, Ludovic Halévy. In the drawing, Halévy himself appears; top-hatted and bearded, he is shown entering the dressing room at the Paris Opera, where he pauses to address Madame Cardinal, mother of two adventurous daughters, who looks up from her newspaper in response. But it is the cropping that enhances both the immediacy and drama of the scene, a technique stolen from photography. Next to this engaging Degas in the exhibition is Manet’s leadpoint and ink-wash sketch, The Rue Mosnier in the Rain (1878), with its scattered pedestrians clinging to umbrellas and jolting carriages drawn by horses.

For many, it might be a surprise to find Degas’s Woman at a Window (1870–71) in an exhibition of Impressionist drawings. It usually hangs among the Impressionist paintings in the Courtauld Gallery. It is, however, painted not with oil paint but with ‘essence’, that which remains when oil is taken out of oil paint and the remaining solute is mixed with an organic thinner such as turpentine. It has a faster drying time than oil and would have allowed Degas to work fast, as if extemporising. Much disappears into indeterminacy, leaving the minimum of information – the empty chair, the woman, the window and its curtains – to create the necessary balance of lights and darks, transparency and solidity. The woman’s two hands rest in her lap; it is the weight of the hand nearest to the viewer, with the light running along its side, that seems to hold the whole picture in position.

Dancer Seen from Behind (c. 1873), Edgar Degas; a work made using ‘essence’. Collection of David Lachenmann

During the second half of the 19th century, drawing achieved a higher status. No longer merely a preparatory tool, nor merely just a method for training of the eye, it gained a new autonomy. Its growing importance is shown by the fact that many artists who came later owned drawings by the leading Impressionists as a kind of talisman or source of inspiration. In the catalogue, Christopher Lloyd argues that the Impressionists’ willingness to experiment gave to their drawings a more deliberate involvement with new ideas. Pastel became popular at this time partly because it was easily portable and versatile, capable of supporting lively hatching as well as silky smoothness. Both are found here in Portrait of Marie-Thérèse Gaillard (1894) by the American-born Mary Cassatt, who arrived in France in 1874 and was invited by Degas to exhibit with the Impressionists. She produced outstanding pictures of women and children, free of sentimentality.

One of the earliest people to recognise the importance of drawing within the development of Impressionism was Edmond Duranty. In his pamphlet La Nouvelle Peinture (1876), timed to coincide with the Second Impressionist Exhibition, he dismissed the regulations imposed by the École des Beaux-Arts, and insisted that what was needed was ‘penetrating draughtsmanship, consonant with modern beings and other things’. In other words, he wanted the special characteristics of a modern individual – ‘in his clothes, in social situations, at home, or in the street’. He also noted that artists were trying to create from scratch ‘a wholly modern art, an art imbued with our surroundings, our sentiments, and the things of our age’.

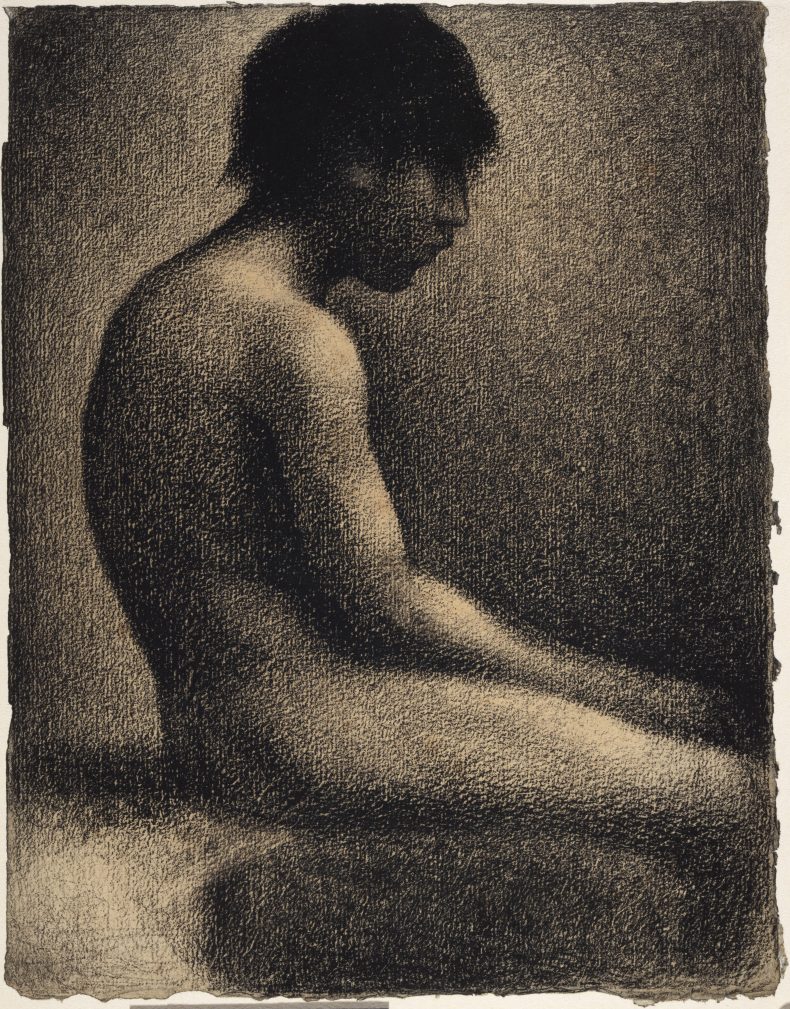

There is an intimacy to this show which encourages openness to the far from finished nature of many of these works and gives attention to their momentary effects. There are, though, moments when the visual conversation linking the exhibits feels weak, as if lacking more choice examples. Halfway through, the exhibition moves into another subject, namely the role played by drawing in the Post-Impressionist period, which is a differently nuanced subject, especially when we move into the dreamworld of Odilon Redon. Admittedly this second half is studded with interest, in the form of Van Gogh’s The Entrance to the Pawn Bank, The Hague (1882) and Seurat’s superlative study of 1883 for one of the swimmers in his Bathers at Asnières. With works of this calibre, this is an exhibition that should not be missed.

Seated Youth (Study for Bathers at Asnières) (1883), Georges Seurat. National Galleries of Scotland

‘Impressionists on Paper: Degas to Toulouse-Lautrec’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 10 March.

From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home