Simon Starling’s mixing of modernism, Noh theatre and contemporary stagecraft has resulted in a series of works that explore cultural overlapping and shifting identities. He talks to Maggie Gray about his new show at the Japan Society, New York

‘At Twilight’ explores the influence of Japanese masked theatre on Western modernism. What first attracted you to the topic?

It goes back to another work that I made for an exhibition in Hiroshima, about a sculpture by Henry Moore. I discovered that this sculpture had a double identity. In Chicago [where the final version resides] it was called Nuclear Energy [1964–66], which of course is a positive thing. The version in the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art [a working model] was called Atom Piece and had a completely different significance. I was intrigued by that. I developed a project – a kind of proposition for a piece of theatre – which overlaid the narrative of a Japanese Noh play, Eboshi-ori, and the narrative of the evolution of Moore’s sculpture. For me Noh was about exchanging your identity on stage. It seemed like a nice device to investigate this other story.

How did it develop into the current piece?

When I was researching that project I discovered a story of W.B. Yeats doing something similar – taking the modes and manners of Noh theatre and using them in a modernist context in London in 1916. He put on a hybrid, neo-Noh production, basically a piece of Irish folklore retold in the manner of a Noh play. I was interested in this moment of collaboration between different cultures and generations. You had Ezra Pound, working as Yeats’s secretary, who was finishing the translations of some Noh plays; this young Japanese dancer Michio Itō who came to London from Berlin at the beginning of the war and [joined] their avant-garde circle; Edmund Dulac, a French book illustrator who had started to work in theatre and got involved, and so on. The project in Glasgow and New York is reiterating that for the contemporary moment. I’ve put together a collaborative team to realise a piece of theatre which is also a hybrid. It is in part a reworking of Yeats’s At The Hawk’s Well, but then there are different levels: there are the characters of Yeats and Pound who are staging the play, and then there are the characters of myself and Graham Eatough, the theatre director I am working with, who are staging those stagings. It’s very layered, [with] constant identity shifts from one generation to the other, from one culture to the other.

How does the work you recently presented at the Common Guild in Glasgow relate to the Japan Society exhibition?

In Glasgow the work existed as a presentation of the various costumes and props and masks, and some contextual information: then [there was] the realisation of the play in three performances in a beautiful garden at Holmwood House. In New York we’re building a more historical exhibition. We’ve been loaned objects which have a direct relation to that moment in 1916 – an Epstein Torso in Metal from Rock Drill, a beautiful Brancusi sculpture of Nancy Cunard, who was one of the hostesses of the original performance, and so on. And the Japan Society is going to stage performances of some of the Noh plays that Pound was involved in translating.

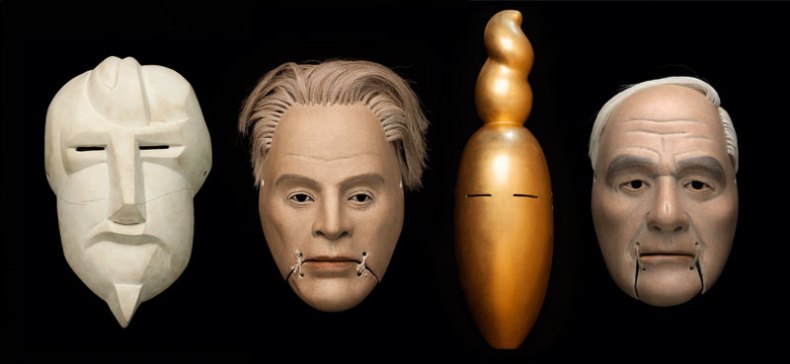

Simon Starling’s (b. 1967) masks of Ezra Pound (after Henri Gaudier-Brzeska), W.B. Yeats, Nancy Cunard (after Constantin Brancusi) and Henry Moore. Courtesy the artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow/Henry Moore; photo: Ruth Clark

You’ve created new costumes and choreographies: how closely do they relate to the original modernist works?

Some are facsimiles of designs by Edmund Dulac for the original play, but they’re made in greyscale. All we had were black and white drawings and photographs, and I decided it would be nice to stick with what we know. There’s also a rather beautiful Eeyore pantomime costume for two actors, so Yeats and Pound will become, at certain times in the play, Eeyore as well. It’s an embodiment of collaboration – two people coming together to become one beast. The reason for Eeyore is that Ashdown Forest, where Yeats and Pound were living in 1916, was eventually the context for A.A. Milne’s story. Then there’s a collaboration with Javier de Frutos, facilitated by the Scottish Ballet. He agreed to choreograph the ‘Hawk’s dance’ – the culmination of Yeats’s play – based on modern dance and drawings by Dulac. In a way it’s all about gossip: this play was performed to so few people, there’s very little known about what actually happened on that stage. For [Javier de Frutos] it left an intriguing, open space to work within.

Do you know where you want a project to go before you start it?

If you don’t have a good idea of the trajectory from the beginning then it can’t really function. But there’s so much richness brought to the process by different collaborators. The mask-maker Yasuo Miichi brings all his know-how, and Joshua Abrams who is doing the music is bringing a different body of experience. It’s a treat to be at the centre of all of that and try to hold it on some sort of path…It’s been a real privilege actually.

How challenging is it to present your research visually?

It’s an experiment. I’m not a theatre person but it does offer possibilities for storytelling, which is what I’m about. There’s a tension in the play between Graham’s character wanting to get on with the performance and me being more interested in explaining the context. So there’s an overt sense of a process of negotiation and discovery in the play itself. And the objects carry so much: it’s a very physical experience to watch. I think what’s really important is how [the project] embodies time. It was made over a long period – five years or so – and you can feel that in the objects. Not just five years, in fact – it goes back to 1916 and beyond to the beginnings of Noh theatre…It’s really about a collapse or a condensation of time. When the work is at its strongest that’s how it feels.

Photo: Mikel Patrick Avery

‘Simon Starling: At Twilight’ takes place at the Japan Society, New York, from 14 October–15 January 2017.

From the October issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?