‘I think there’s something wrong with my mind,’ Jacqueline de Jong says with a laugh. She is casting her eyes around the paintings in ‘Resilience(s)’, a show at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery in London, when her gaze falls on Ceux qui vont en bateau (1987): a monumental work from her Paysages dramatiques series. A group of contorted beasts intertwine – in conflict or embrace – in front of a landscape that is divided by spiky green foliage into triangular planes of blue sea and vermilion sky. ‘But what are they supposed to be?’ asks the artist, looking at the figures before her. ‘A horse? A cow? And what are they doing on top of that boat? God knows what.’

Monstrous figures are a recurring presence in De Jong’s painting – and a leitmotif in an otherwise tremendously varied career that has seen her move between painting, sculpture, jewellery, books and printmaking. Last year she had a major retrospective at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, but this, somewhat remarkably, is the first solo exhibition of her paintings in the UK. De Jong remains best known in this country for her involvement with the Situationist International, the anarchic avant-garde movement led by Guy Debord. From 1962–67, after having been ousted from the ‘official’ movement by Debord, she edited The Situationist Times, the key English-language mouthpiece for Situationist principles of chance, spontaneity and play as means of disrupting the status quo.

Chance and spontaneity inform her approach to painting in a different way. They enable a responsiveness to the materials at hand, allowing concerns of colour, or of the values of opacity and transparency of the paint, to guide the composition. It is to these that our conversation turns as we walk around the exhibition and she recalls the act of painting the works on display three decades earlier.

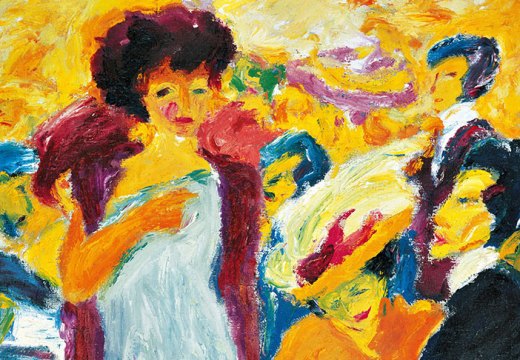

Drôle de la chasse frustrée (1987), Jacqueline de Jong. Photo: Todd White; courtesy the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London; © Jacqueline de Jong

The seed of her series of Paysages dramatiques, which make up the bulk of the show, was planted after a flight the artist took across Jutland. ‘I was in a small plane, quite low to the ground. I saw these yellow fields of rapeseed below me, and I was triggered by the colours.’ What followed was her first extended foray into the genre of landscape – a group of vivid essays in primary colours, more painterly than anything that had gone before. In Le paysage marine dégonflé (1987), waves of green and blue lap at the hull of a small boat, the scene set against a looming red mountainside, in the background, and in the foreground a beach of buttery yellow. The artist speaks to me with wonder of the oceans off the northern point of Jutland, ‘where the Baltic and the Northern Seas get together, and enclose one another’. But the painting is anchored by a human note: the small, empty rowing boat, rendered both in murky brown paint and by the softer brown of the marouflé paper beneath. ‘I needed the boat to give structure,’ the artist says. ‘To give the sense of movement – without it, the whole thing would be silly.’

Bateau ivre en détresse (1987) Jacqueline de Jong. Photo: Ben Westoby; courtesy the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery London; © Jacqueline de Jong

A sense of conflict asserts itself more pointedly in Drôle de la chasse frustrée (1987), another work from the series, which makes use of the same simple palette, and the same lustrous quality of oil applied directly to paper, to depict amorphous beasts tussling over a rifle. De Jong describes another venture into the countryside – this time to the island of Schiermonnikoog off the coast of northern Holland – and the anger at finding pheasant-shooting in an environment where the animals were so plentiful and trusting that you could just ‘reach out your hand and grab one’. It’s what she calls a ‘sociological interpretation’ of the cruelty of hunting, one that, as so often in her work, blurs the distinction between man and beast. Elsewhere, in Big foot small head (for Thomas) (1985) – something of an outlier in the exhibition, but an example from another series of 25 works completed at around the same time for the stairwells in Amsterdam City Hall – a figure with misshapen features stands on a staircase, feet turned in opposite directions. Under his right foot, a crocodile is trampled. ‘Looking at it now,’ De Jong says, ‘what I’m most interested by the sense of something shining through the body. It’s only the shoes, hat and the animal that are really painted.’

Looking at the ‘animal’ I ask De Jong if she enjoyed the subversive aspect of peopling the town hall with her monstrous creations. A hint of mischief flares in her eyes: ‘Well yes, of course, but I didn’t want to make that obvious. I never want to make anything obvious.’

Big foot small head (1985) Jacqueline de Jong. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij; courtesy the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London; © Jacqueline de Jong

‘Resilience(s)’ is at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London until 18 January 2020.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home