From the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

At his death in 1825, Jacques-Louis David was the most famous artist in Europe. He was the man who had brought neoclassical painting to rapid perfection; his pictures were public works that had both predicted and shaped the French Revolution; he himself had been an active participant during the Revolution’s bloodiest years before pledging his allegiance and his brush to Napoleon; and he was the teacher whose students and adherents would help define the art of the early 19th century.

However, if both David and his paintings were celebrated – or reviled, depending on the political orientation of the viewer – then his drawings, the foundation of everything he produced, were almost unknown. More than 2,000 of them were included in the sale of his estate in 1826 and the author of the catalogue, Alexis-Nicolas Pérignon, was in no doubt about their importance. ‘It will be easy,’ he wrote, ‘to follow step by step, in these studies, the progress of the one who raised the [French] school rather suddenly from a mannered and languid style to a rigour and a purity worthy of the great masters of Italy.’ These, then, were not just works of art but historical documents.

Frieze in the Antique Style: Death of a Hero (1780), Jacques-Louis David. Musée de Grenoble. Photo: Jean-Luc Lacroix; City of Grenoble/Musée de Grenoble

Nevertheless, only two of his drawings had previously been exhibited in public. At the Salon of 1783, David showed Frieze in the Antique Style, a grisaille strip seven feet long (subsequently cut into two pieces) depicting the death and funeral procession of an antique hero and in 1791, The Oath of the Tennis Court, a teeming image of the moment the Revolution flared into life.

David’s thinking behind their public showing was pragmatic: the first, for the ambitious 35-year-old, was to announce the new classical manner, forged in Rome, with which he was about to remake contemporary French painting; and the second, for the de facto official painter of the Revolution, was an advertisement meant to attract donations for a huge canvas of this foundational moment to be hung in the National Assembly. At the Salon, it was displayed beneath The Oath of the Horatii (1784), to drive home the kinship between antique and Revolutionary virtue. For the rest of his career, however, David kept his drawings for the exclusive use of himself and his students or as gifts to friends and collaborators.

Over the course of his career, David was the key figure in giving pictorial form to the last days of the Ancien Régime, the squalls of the Revolution and the Napoleonic adventure. As he did so he segued between the styles of the era, from late rococo to neoclassicism to proto-Romanticism before retrenching to soft classicism. Drawings were indispensable to his practice. The importance of his graphic output is the theme of a major new exhibition, ‘Jacques-Louis David: Radical Draftsman’, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (17 February–15 May).

Despite his prolificacy, what David’s drawings rarely show, unlike those of his students such as Antoine-Jean Gros, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, is a strong sense of the man himself. For David, drawings were utilitarian objects – a record of what he had seen and, more importantly, a tool for the composition of paintings. The canvas was paramount and drawn motifs – shuffled, mixed, cut and pasted, traced and adapted – were the means of giving paintings the clarity he desired.

Although the young David was a poor scholar, he recalled, whether truthfully or not, making good use of his time: ‘I was always hiding behind the instructor’s chair, drawing for the duration of the class.’ His father, a Parisian iron merchant, was killed in a duel in 1757 and the boy was passed into the care of two maternal uncles, both architects – François Buron and Jacques-François Desmaisons – and a career in architecture seemed likely until he expressed his desire to be a painter. (He would later always struggle with the perspective of architecture in his pictures.) His teacher was due to be another relative, François Boucher, who advised him instead to join the studio of the classically oriented Joseph-Marie Vien. ‘He is a bit cold,’ said Boucher, ‘but come to see me from time to time and when you bring me your work I will correct Vien’s coldness and teach you my warmth.’

From 1766, under Vien and at the Académie, David learned the fundamentals of drawing after casts from antique statuary and life models – Vien himself employed a model in his studio three times a week. Vien’s own work at this period was, in Anita Brookner’s memorable phrase, marked by ‘unparalleled flaccidity’ and, for all his affection for this surrogate father figure, David seems to have been little influenced by him. His mind was set on winning the Prix de Rome, which he entered in 1771 against Vien’s advice, in 1772 (failure that year led him to lock himself in his room and go on hunger strike for a fortnight) and 1773, before success finally came in 1774 with his interpretation of the Académie’s stipulated subject, Antiochus and Stratonice.

When Vien was appointed director of the Académie de France à Rome, David accompanied him to start his own pupillage. Faithful by instinct – and a young man’s certainty – to Boucher’s style, David was adamant that ‘the antique will not seduce me’ but he quickly recanted, ‘ashamed’ of his ignorance. Over the course of his five years as a pensionnaire in Rome he was irreversibly seduced. According to his friend the archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir, ‘like a schoolboy he set about drawing, for a whole year, eyes, ears, mouths, feet and hands and was content to execute complete ensembles after the most beautiful statues’.

He made some 1,000 sketches in all, two-thirds of which showed ancient sculptures and artefacts, some 200 copies of either details or complete compositions after Renaissance and baroque paintings (an eclectic roster from Raphael to Veronese and Van Dyck) and the rest depicting Roman landscapes. The drawings were rarely highly detailed or polished but, in black chalk sometimes worked up with grey wash, lucid recordings of useful or striking motifs. He later cut and pasted them on to larger sheets in albums in an order designed to aid his compositional method. During his second trip to the city, in 1784 to paint The Oath of the Horatii, he wrote: ‘I work during the day on my picture and in the evening I draw after the antique.’

The Rome sketches were to be a vital resource to David for the rest of his career, not least in the composition of the three great works of the 1780s that established his name and the superiority of his new, severe form of history painting, The Oath of the Horatii (1784), The Death of Socrates (1787) and The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of His Sons (1789). These were hard-won paintings, each the result of a great deal of trial, error, sifting and rearrangement.

Using his Rome drawings as a starting point, he established a method that he would replicate in all his major canvases. First, with his sketchbooks in front of him he would draw in the figures; next came the architectural backdrop, then the placement of the poses. As the composition developed, he would concentrate on individual figures, often drawing them in the nude to start with. The tableau was then further refined through more careful drawings showing the whole scene and using grey washes to check the fall of light. The preferred scheme was transferred to a further sheet and oil paint added to establish the colours. Then he made large black and white chalk drapery studies before everything was squared up and transferred to the canvas for painting.

The whole process was further informed by reading, consulting scholars, and attending theatrical performances, such as Corneille’s play Horace and the chevalier Noverre’s ballet Les Horaces et les Curiaces. It could be a lengthy business: David conceived the idea for The Death of Socrates in 1782 but took five years to bring it to life.

The Death of Socrates (c. 1782), Jacques-Louis David. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Death of Socrates (1782), Jacques-Louis David. Private collection

The Death of Socrates (1787), Jacques-Louis David. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

If the three moral admonition canvases of the 1780s made it to fruition, drawings in various stages of his process are all that remains of a series of compositions that David never realised. The Death of Camilla (1781), a later episode in the Horatii story, was superseded by The Oath of the Horatii; Caracalla Killing His Brother Geta in the Arms of His Mother (1782) and The Ghost of Septimius Severus Appearing to Caracalla after the Murder of His Brother Geta (c. 1783) were perhaps too melodramatic for the restrained and austere manner he was perfecting; The Departure of Marcus Atilius Regulus for Carthage (c. 1786) would have made an ideal and forceful fourth painting of an exemplum virtutis; while perhaps he recognised that his Allegory of the Revolution in Nantes (c. 1789–90), and The Triumph of the French People (1794) were too allegorical for a painter who liked to ground his work in reality. By the time he was ready to put brush to canvas for The Oath of the Tennis Court too many of its leading figures had fallen from favour for it to remain a feasible topic.

The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of His Sons (c. 1787), Jacques-Louis David. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

All nevertheless show how he would transform his Roman sketches during the act of picture making (although not in the case of the head of Brutus in The Lictors, which was reproduced accurately from his drawing of a bust of Brutus in the Capitoline Museum). Étienne-Jean Délecluze, a student of David’s and his first biographer, recorded the painter giving him a drawing showing two heads, one crowned with laurels, copied from the antique. The painter said:

Here is what I call antiquity in its raw state. When I had carefully and laboriously copied the head, I went home and ‘put some sauce on it’, as I used to say in those days. I made the brow a little knitted, I pushed up the cheekbones, I opened the mouth a bit. Finally I gave it what the moderns call expression.

This habit of recasting the antique was instinctive as much as pragmatic. When he started to paint the Revolution he saw unfolding current events in terms of antiquity. The deputies in The Oath of the Tennis Court pledge themselves to the formation of a new constitution with the outstretched arms of the Horatii brothers taking their own oath – indeed, in real life, the deputies may have been aping the painting; in The Death of Marat (1793), the murdered radical, slumped in his bath, is an adaptation of David’s morceau de réception for the Académie Royale, Andromache Mourning the Death of Hector (1783), complete with a void in the upper half of the picture; and on first meeting Napoleon, David returned to his studio and told his students: ‘What a beautiful head he has! It is pure […] beautiful like the antique.’

It was during the Revolutionary years, when David, an ardent Jacobin, was elected to the Committee of General Security (responsible for policing) and the Committee of Public Instruction (responsible for social and educational reforms) – both reporting to Robespierre’s Committee of Public Safety – that, according to a passage in The Percy Anecdotes, a hugely successful miscellany of contemporary snippets and stories, David’s drawing took on a different hue. During the Terror, he not only attended the execution of his former friends Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins – apparently ‘for his improvement in the art of painting’ – but also hurried to the La Force prison in the aftermath of the massacre of its political internees to draw, as he supposedly said, ‘the last convulsions of nature in these scoundrels’. If the grisly story is true, the drawings have not survived.

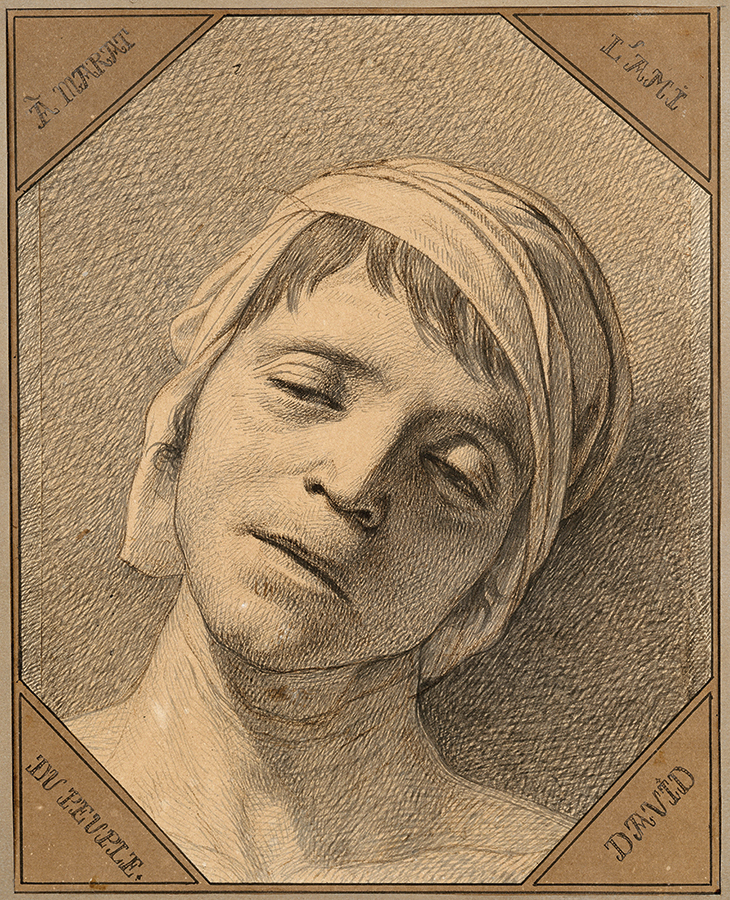

Nevertheless, the rapid sketch he made from a window of the haggard but defiant Marie Antoinette as she was taken by tumbril to the scaffold does exist, as does the careful drawing he made of Marat’s face shortly after his assassination. The Marat drawing was made for an engraving but that of the former queen is a record of a historic incident and perhaps also an expression of David’s morbid or gloating excitement.

If these episodes suggest that David’s drawing, certainly in the proximity of death, wasn’t always so considered, then by the time he made a series of pen and wash portraits of fellow prisoners – like him, Jacobins incarcerated following the fall of Robespierre – he had himself back under control. Although he and his confrères feared the guillotine, David drew them in profile and in detail, with an acute understanding of the anxiety that clearly marks their features. If these were to be the last images made of his friends then he was determined to depict them with both care and fidelity. While the nine existing small round portraits reflect the contemporary taste for the format popularised by Charles-Nicolas Cochin II, they also hark back to classical and Renaissance portrait medallions.

The Head of the Dead Jean-Paul Marat (1793), Jacques-Louis David. Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource NY

The advent of Napoleon, and perhaps too the success of his student Gros, forced David into compositions more complicated than he had so far realised. Although Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, commissioned in 1800, had the clarity of his pre-Revolutionary paintings, works such as The Coronation (1807), and The Distribution of the Eagle Standards (1810) – two of a projected four-work scheme – required even greater planning than the taut paintings of the 1780s.

The Coronation – for which The Oath of the Tennis Court proved to be a form of ironical trial run – took a year of planning on paper, the making of 50 portrait drawings of individual participants, the assistance of the Paris Opéra’s set designer Ignace-Eugène-Marie Degotti for the architectural setting, the making of a scale model of the interior of Notre Dame complete with figurines, and the participation of his students to transfer his drawings to canvas. Then, David wrote, ‘I shall reposition the figures that might not work but I can do that only by seeing everything together.’ One of those changed figures was that of Napoleon himself: David had intended to show him in the act of self-coronation but at a late stage in the process, changed the focus to the freshly minted emperor crowning Josephine.

With Napoleon’s exile and the restoration of the Bourbons, David was banished – doubly damned as both a regicide and the deposed emperor’s First Painter and propagandist. He left for Brussels while his students fruitlessly petitioned the new government for an amnesty and his safe return. He nevertheless remained true to his principles, refusing to paint a portrait of the Duke of Wellington, writing: ‘I have not waited 70 years to defile my brush. I would rather cut off my hand than paint an Englishman.’ Instead, exile led to a return to the antique – and his younger self. He told Gros, whom he ceaselessly hectored into adopting classical subjects, that while painting Cupid and Psyche (1817): ‘I work as if I were only 30 years old; I love my art as I loved it when I was 16, and I will die, my friend, brush in hand.’

He made new drawings too, including 32 black chalk ‘croquis, caprices, if you like’ of antique themes, which he started ‘without much real intent… but then my pride got involved and I made real drawings’. They were not, it seems, intended for paintings. It had taken a lifetime of making drawings for the sake of utility but in 1818 he could admit ‘that this collection of drawings deserves a place among my works’. This was the man a student reported as wanting ‘nothing to do with finished drawings’.

David died in 1825, after being hit by a carriage when leaving a theatre. Only then did the scale of his engagement with his drawings come to light, and how vital they were to his conception of a masterpiece being dependent on ‘a combination of thought and indefatigable perseverance on the artist’s part, as he tries to bring his work to completion’. Regardless of what they show, his drawings are also, without doubt, images of his own indefatigable perseverance.

‘Jacques-Louis David: Radical Draftsman’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from 17 February–15 May.

From the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home