‘This figure,’ wrote Théophile Gautier when he saw Jean-François Millet’s The Sower at the Paris Salon in 1850, ‘seems to be painted with the very earth that he is sowing.’ In full length, a young man emerges dynamically from a maelstrom of dark browns and yellows, blurred and indistinct but purposeful. The picture’s tones and brushstrokes blend into one another so that he seems to be made of the landscape he works, both part of his environment and in charge of it. A similar effect is achieved in A Sheepshearer (1860), where the pink and white shades of the shearing woman’s clothing connect her to the creamy-pinkish exposed skin of the animal and its discarded fleece. Like the sower she dominates the composition, and there is a monumental quality to the strength and rigour of her posture with the knife, as if she has been carved in marble. The positioning of these peasant figures – centre stage, on large canvases – was considered subversive and even radical when they were first exhibited in Paris, not long after the revolution of 1848. Millet, conservative critics argued, was using his art to intervene in live economic and political debates.

The Seaweed Gatherer (c. 1890), Paul Sérusier. Indianapolis Museum of Art, Newfields

Take The Gleaners (1857): in the context of contemporary moves to force peasants to pay for the privilege of gleaning scraps from the harvest, its dignified portrayal of three bending figures could be read as a radical statement of the importance of charity to society’s poorest. The Van Gogh Museum exhibition ‘Jean-François Millet: Sowing the Seeds of Modern Art’ invites us to take another look at Millet through the eyes of his contemporaries, to reclaim something of the excitement and political charge his works carried before modernist critical appraisals in the 20th century pushed him into the background. It also invites us, by means of an extraordinary display of loaned works, to understand Millet’s importance as a political and artistic progressive to many well-known painters who came after him, Van Gogh, Seurat, Pissarro, Cézanne, Monet, Dalí and Picasso among them.

Works taking inspiration from a Millet painting or drawing are displayed clustered around their model, an effective curatorial approach that encourages viewers to spot repeated motifs and quotations. The bent working bodies of The Gleaners return in Seurat’s Peasant Labouring (1882–83) and The Stone Breaker (1882); in Max Liebermann’s Potato Harvest at Barbizon (1875); in Paul Sérusier’s The Seaweed Gatherer (c. 1890); in Van Gogh’s sketches of peasant women gleaning and digging; and so on. Monumental peasant figures are everywhere once you start to look for them. There is Malevich’s The Woodcutter (1912), built up of flat abstract cylinders and cones, but presented full-length and in harmony with his environment in the Millet manner; Ferdinand Hodler’s The Reaper (1909), in which the figure is bent over but heroically strong, dwarfing his surroundings and the thin skeleton of a tree behind him; and Paula Modersohn-Becker’s Old Peasant Woman (c. 1905), pious and dignified, a figure of extraordinary mass and presence.

The Siesta (1889–90), Vincent Van Gogh. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

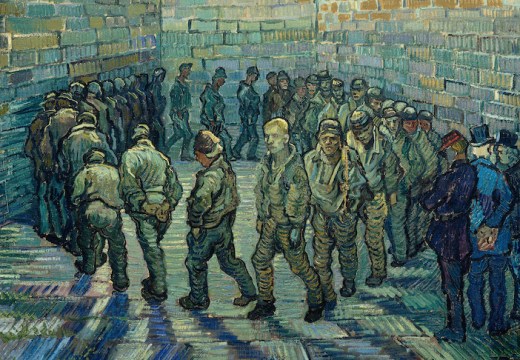

Van Gogh drew on Millet as a model from his earliest days as an artist. Making copies of Millet prints was one of the ways he taught himself to draw, and The Potato Eaters (1885), his first large-scale figure piece, was conceived as a Millet-inspired scene of peasant life rendered in the dark brown palette of The Sower. The exhibition shows us what happened when he embraced vivid colour and applied it to Millet’s forms. His Evening (1889) – after Millet’s pastel Winter Evening (1869) – has colour pouring out of the lantern swinging at the rear of the picture, picking out the features of the sewing woman in a pale yellow, the shadows striated in complementary tones of violet and blue. In The Siesta (1889–90), after another Millet pastel, Noonday Rest (1866), the heat of midday is palpable in the heavy bright blue of the sky.

The Angelus (1857–59), Jean-François Millet. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

There are some interpretations Millet might have found it harder to predict. For Dalí – who was obsessed by the picture and wrote a book about it – Millet’s The Angelus (1857–59) wasn’t to be read as a tranquil portrait of a couple praying for their crop to the sound of evening church bells. In the curved body of the woman, inclined slightly forward, he saw a predatory attitude; and in the man’s positioning of his hat near his groin, an attempt to protect himself from castration – or conceal his arousal. His Meditation on the Harp (c. 1933) eroticises Millet’s upright pitchfork and makes the placing of the hat more explicit, while his powerful naked female figure is shown as the dominant force in an Oedipal trio. Dalí’s Millet is unlike Van Gogh’s Millet or Seurat’s Millet, or Monet’s treatment of Millet’s haystack motif; but each artist shares an essential conviction about his modernity.

‘Jean-François Millet: Sowing the Seeds of Modern Art’ is at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until 12 January 2020.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home