When Joan Mitchell and Jean-Paul Riopelle met in Paris in the summer of 1955, Mitchell had already made a name for herself in the male-dominated world of Abstract Expressionism. Her work had been featured in the 9th Street Art Exhibition organised by Leo Castelli in 1951 along with pieces by other notable members of the New York School, and was later exhibited in the Stable Gallery follow-up shows. Riopelle, who was born in Canada but moved to Paris in 1947, also had a career before their encounter. He was close to Matisse’s son-in-law, the critic George Duthuit, and alongside artists like Jean Fautrier was associated with what was at the time the closest European relative of Ab Ex: Art Informel. ‘And then I got involved [with Riopelle], and that sort of screwed up everything,’ Mitchell later recalled. Their time together would be marked by passion and rivalry.

Tilleul (Linden Tree) (1978), Joan Mitchell. © The estate of Joan Mitchell

It is this period that provides the framework for the exhibition of Mitchell and Riopelle’s work currently at the Fonds Hélène & Édouard Leclerc in Brittany. With some 60 paintings, punctuated by charismatic photographs of the pair, the show argues that their works enriched, and were also in conflict with each other. After two Canadian showings in Québec and Toronto, the current venue near the rugged coast and wild beaches of Finistère (the very western tip of France) is a germane backdrop for the spasmodic rhythm and fierceness of their work. Take for example Mitchell’s Untitled (La Fontaine) (1957), the dabs, streaks, and drips of which evoke the agitation caused by the gusts of wind typical of this region.

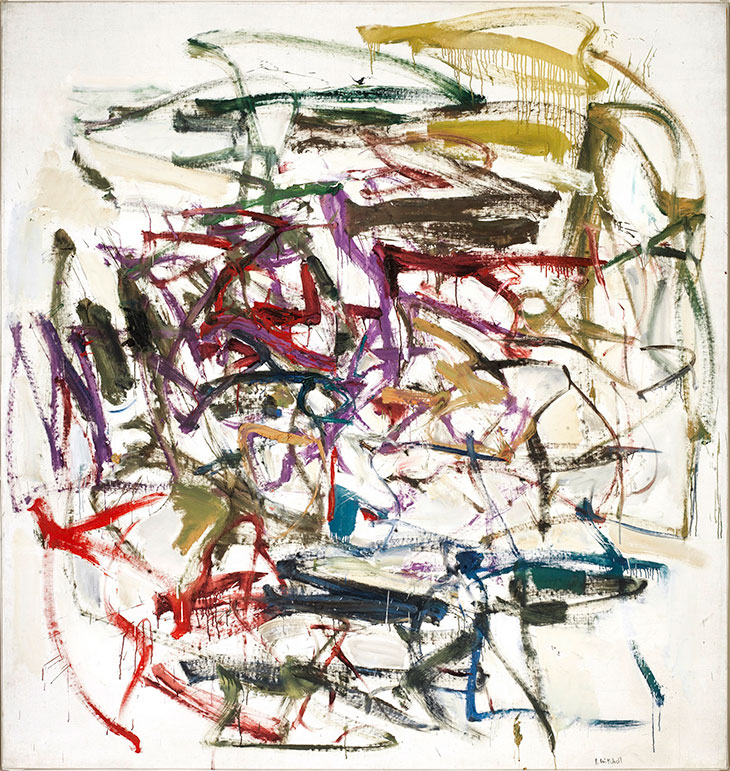

The first room displays works predating the relationship. Notable here is Riopelle’s 15 Horsepower Citroën (1952), composed of mosaic-like juxtapositions of small, impastoed rectangles of paint. The painting, in what would become his signature style, has the look of a highly pigmented Google Earth photograph. A similar palette is deployed in the more graphic brushstrokes of Mitchell’s Untitled (1952–53), which recalls the scrawls of fellow Ab Ex painters Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning.

15 Horsepower Citroën (1952), Jean-Paul Riopelle. © The estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle/ADAGP Paris 2018

The rest of the exhibition is arranged chronologically, tracking the places where they created their work: rue Frémicourt in the 15th arrondissement, where they first lived together; Vétheuil, Mitchell’s house on the banks of the Seine where they moved in 1967, not far from Riopelle’s later studio in an airplane hangar in Saint-Cyr-en-Arthies. The works from the 1950s are probably the ones in which their kinship is the strongest, but what strikes me from the very first room is that while the artists are equally represented, the exhibition makes it clear that Mitchell’s imagination was incomparably superior.

Their stormy brushstrokes are not of the same nature: the primary colours of Riopelle’s Untitled (1958) contrast with the more complex hues of Mitchell’s Untitled (1957). As the canvases of both grew in tandem with the sizes of their studios, Riopelle’s works remained in the same style. Commissioned by the Toronto airport, his five-panel Meeting Point (1963) is heavily built up and made of kaleidoscopic streaks of colours, a technique reminiscent of the paintings from the 1950s. By contrast, Mitchell’s powerful sense of composition and frenzied swatches of colours ring with originality and urgency. Her style is less formulaic, alternating between all-over and figure-ground. Some of her works, such as Girolata (1964), are animated by a centripetal force and imbued with a form of lyricism; they might have inspired Cy Twombly. But hers are less perfect – and perhaps, therefore, more disruptive. Monumental polyptychs such as Chasse Interdite (1973) achieve a masterful balance through repetition, evidence of Mitchell’s emancipation from Ab Ex.

Untitled (1957), Joan Mitchell. © The estate of Joan Mitchell

The exhibition tells the story of Mitchell and Riopelle’s life together; there is just one work, by Mitchell, from after the end of their relationship (in 1979, after Riopelle’s many infidelities) – an untitled diptych from 1992 featuring two explosions of colour against a pale backdrop. But while the show retraces their output as a couple, Mitchell is the real star here.

‘Mitchell | Riopelle: Nothing in Moderation’ is at the Fonds Hélène & Édouard Leclerc, Brittany until 22 April.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home