On 7 July, UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee announced the addition of Jodrell Bank Observatory to its list of significant sites. It’s a coup for the management and staff of the site as well as for the University of Manchester, which owns and operates it – all the more remarkable for a facility that just a decade ago was in danger of defunding and closure.

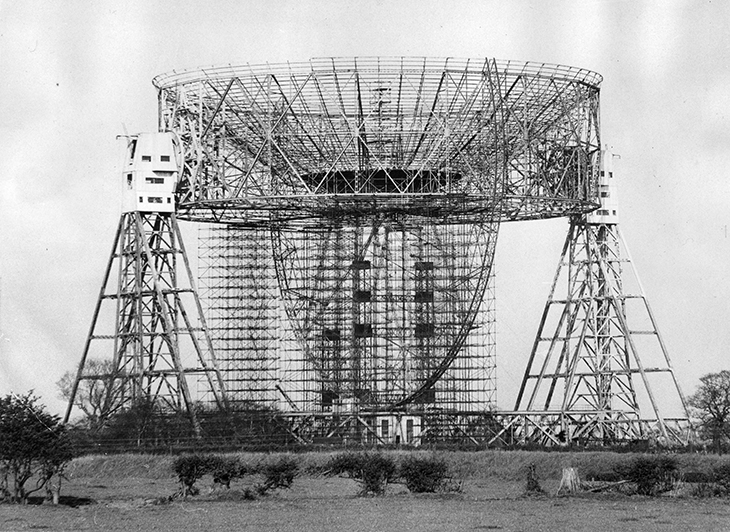

The radio telescope at Jodrell Bank under construction in 1957. Keystone/Getty Images

The largest structure for miles, and symbol of the observatory, the vast dish of the Lovell Telescope – 250 feet in diameter – rises over the Cheshire landscape like the baptismal font of the British space age. Completed in 1957 (as the ‘Mark I’ radio telescope), it became operational just in time to track the launch of Sputnik; 30 years later, it was renamed after the first director of the observatory, Sir Bernard Lovell, who had instigated its construction. Even before the telescope had been built, its creator was famous enough for the television writer Nigel Kneale to borrow his first name for Bernard Quatermass, the hero of his classic BBC sci-fi drama The Quatermass Experiment; later the structure itself would provide the backdrop for the death of Tom Baker’s Fourth Doctor and his regeneration into Peter Davidson in an episode of Doctor Who.

The UNESCO press release emphasises the ‘substantial scientific impact’ of Jodrell Bank’s ‘exceptional technological assemblage’, though the UK government’s nomination dossier also rightly draws attention to the observatory’s cultural significance. Since its inception, the Observatory has played a leading role in a host of cosmological breakthroughs, from the mapping of the sky and the discovery of distant galaxies by means of radio waves to the detection of new varieties of cosmic phenomena, including pulsars, quasars, and the gravitational lenses which occur when the curvature of spacetime bends light around massive objects in deep space. But it has also served both as an emblem of postwar Britain’s scientific achievements and, more recently, as host to numerous installations, events, and festivals dedicated to renewing and expanding connections between the sciences and the arts.

The Lovell Telescope (photo: 2008)

Considering the extraordinary impact of the Lovell Telescope on the local landscape, painterly responses to Jodrell Bank have been surprisingly sparse. An engaging agglomeration of abstract swirls and rectilinear struts by the American artist Frank Roth entitled Jodrell Bank (1964) seems to have been named only after the painting was complete, when a friend showed the artist a photo of the Lovell Telescope in the New York Times. (The resemblance isn’t striking.) A series of screenprints by the local artist D. Alun Evans, and a fine landscape view by the same artist, now in the collections of the Grosvenor Museum in Chester, at least have the advantage of relating to the site itself. Best of all, though at a rather smaller scale, are two Royal Mail stamps on which the telescope has featured, one designed by Ann and David Gillespie in 1966 for a series celebrating ‘British Technology’, and another by Jeff Fisher for the centenary of the British Astronomical Association in 1990.

Jodrell Bank Radio Telescope (1966), designed by David Gillespie and Ann Gillespie

Armagh Observatory, Jodrell Bank Radio Telescope and La Palma Telescope (1990), designed by Jeff Fisher

Since 2016 Jodrell Bank has also played host to Bluedot, an annual festival that celebrates science, art and sound. Lovell was himself a great music lover – he once used a gramophone record of Brahms’s Third Symphony to demonstrate the effects of solar radiation on radio signals – and it’s fitting that the observatory he founded should now play a key role in cultivating collaborations between science and the arts. Headlined this year by Kraftwerk, New Order and Hot Chip, the festival has also, for the last three years, hosted the COSMOS residency, a collaboration with the experimental arts agency Abandon Normal Devices. The inaugural residency saw Daito Manabe and Setsuya Kurotaki’s Celestial Frequencies transform the frame of the Lovell Telescope into a pulsing visual representation of incoming real-time signals from the universe. In 2018, Addie Wagenknecht’s Hidden in Plain Sight covered the same canvas with a flickering lightscape drawn from astronomical observation data and inspired by dazzle camouflage. This year’s commission, a ‘pulsar hunting VR artwork’ by Julie Freeman, plays with the relationship between bodies, data, and the informatic residues of distant stars.

Celestial Frequencies (2017), Daito Manabe and Setsuya Kurotaki, part of COSMOS by Abandon Normal Devices. Photo: © Scott Salt Photography

The UNESCO recognition is, as a number of newspapers and websites have reported, a great moment for British science, and the government’s Heritage Minister, Rebecca Pow, is surely right to say that it will help to ensure that Jodrell Bank ‘will continue to inspire young scientists and astronomers all over the world’. Amid all the justifiable celebration of science and technology, however, it might just be worth remembering the significant role that the arts have played in bringing that inspiration to a wider public.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home