Who is ultimately responsible for the Tate? In the early 1950s Lord Jowitt asked himself this, while he was chairman of its board of trustees. At that moment, when it looked as if the director would have to be sacked, he was uncertain whether the answer was the Treasury or the trustees themselves.

Jowitt’s question reminds us that the Tate Gallery (now divided into Tate Britain and Tate Modern) was then a relatively young museum, lacking the stability of established precedent and still struggling to assert its identity and purpose. John Rothenstein was the director who, after 15 years’ service, came perilously near to being sacked. To some extent the Treasury acted as his shield. Its report into the Tate’s management, which he had requested, came into operation just as criticism of Rothenstein was at its height. Sir Edward Ritson, a senior civil servant from the Inland Revenue, was sent in to investigate both staff and trustees. In the case of the latter, he was, as the author of this book puts it, ‘unimpressed with their ability to say anything logical or objective’.

Yet it was a trustee who proved to be Rothenstein’s saviour. In February 1954, at a private meeting in the home of the shipping magnate Sir Colin Anderson, the trustees were asked to vote on the removal of the Tate’s director. The vote was split equally. Dennis Proctor, who had taken over from Jowitt, could have used the chairman’s casting vote to decide the matter, but one trustee pointed out that no director should be sacked by a divided board. Rothenstein survived, and stayed on at the Tate for another 10 years.

The trustee’s saving remark is mentioned in my centenary history of the Tate but not here. Elsewhere Adrian Clark kindly commends my book, but while I had to cover the history that led to this crisis moment in a matter of pages, he now enriches the story with gripping details and astonishing new facts, many of them drawn from Treasury archives. The book brilliantly uncovers the full extent of the machinations around Rothenstein, as well as his own contributions to the crisis. Taken as a whole, Clark’s book is not a biography of John Rothenstein, but an analysis of his journey through the art world. Inevitably the Tate dominates this narrative, but learning about the preceding years makes the Tate fiasco all the more fascinating.

For many years there was scant evidence that the young John Rothenstein was heading for a stellar career. He performed badly at Bedales, the school at which, in his own words, he spent seven ‘largely meaningless’ years. Oxford suited him no better and he left in 1923 with a third-class degree. Having shown no interest in art up to this point, he began to pay attention to the work of his father and that of his father’s friends. William Rothenstein was an eminent artist, adept at portrait drawings that gained him contacts in academic circles and advanced his position. By the time he became principal of the Royal College of Art, he had developed strong opinions. Although renowned for his kindness and generosity to young artists, his didacticism infuriated many. However father and son always remained very close.

After four years of occasional journalism, intense socialising and active membership of the Savile Club, Rothenstein had arrived nowhere. In a conversation with Evelyn Waugh, whom he had met at Oxford, both admitted that their prospects looked bleak. In Rothenstein’s case, Clark suggests that he needed to get away from his father’s ‘cloying embrace’. He did so by getting a job teaching art history at the University of Kentucky and then at Pittsburgh. If his qualifications were questionable, his connections were good. Information in a Kentucky newspaper, which Rothenstein must have provided, let readers know that he ‘had been privileged in having from his earliest days entry to the innermost circle of the artistic and literary world in London’.

Shortly before he left for America in 1927, Rothenstein converted to Roman Catholicism. This was his mother’s religion, but on the paternal side of his family were German Jewish grandparents, who came to England to engage with the thriving textile trade in Bradford. Their son William abandoned Jewish customs, but during the first decade of the 20th century he visited Spitalfields synagogue in London’s East End, which provided the subject for a series of paintings on Jewish themes. His son, however, seemed to want to rid the family of any association with Jewishness. (This didn’t stop him in the course of his career being the frequent target of anti-Semitic remarks.) In 1933 John wrote a letter to the Jewish Chronicle, criticising the suggestion that ‘Jewish interest’ clung to a bronze head of his wife (by his sister), and avowing that none of the members of his family belonged to the Jewish community, but ‘definitely to another faith’.

Rothenstein could be obtuse and insensitive (and dismissive of the past), as is shown in the account of his first museum jobs in Yorkshire, the region in which his father had grown up. He did not stay long in either Leeds or Sheffield, but as the director of the city art galleries, he did much to improve their profiles and make them notable repositories for civic pride. But there were mistakes and fights during these years and it became obvious that he needed good administrative help in order to succeed.

The ‘Tate Affair’ lasted two years and attracted a great deal of hostile publicity. An unwise appointment introduced an Iago into the museum, who fed information to the press on various deeds and trusts that he knew to be dangerous; Rothenstein had not paid sufficient attention to the terms on which they had been set up and had consequently allowed them to be maladministered. In demonstrating this and other failings, Clark shows us much else besides – about how the English establishment operates in the face of crisis, as well as the sometimes vituperative nature of the art world. He perhaps underestimates the steadying influence of Norman Reid on Rothenstein’s final years, but there is no disagreeing with his final conclusion that Rothenstein left the Tate in a far better state than when he arrived. Reid, when he took over as director, sailed on in much calmer seas.

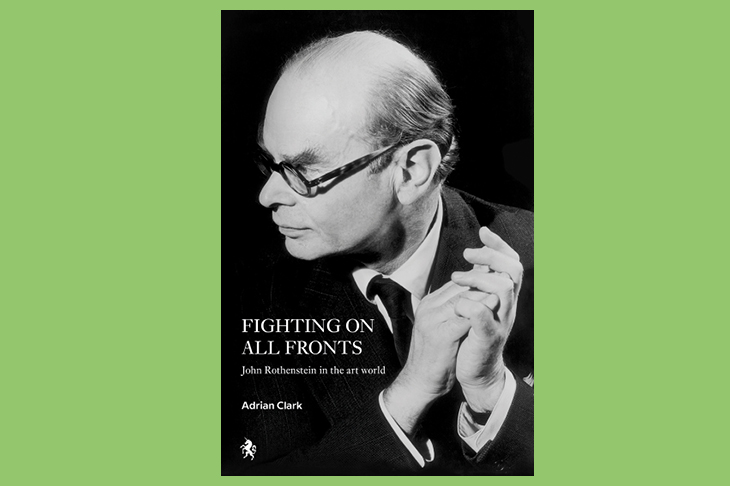

Fighting On All Fronts: John Rothenstein in the Art World by Adrian Clark is published by Unicorn Press.

From the October 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home