From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

A sketch by John Singer Sargent for his famous painting, Madame X, which caused a scandal at the Paris Salon in 1884, not only allows us to see his subject quite differently but fills a long-lamented gap in its new home at the Frick Collection. Curator Aimee Ng tells Apollo the inside story.

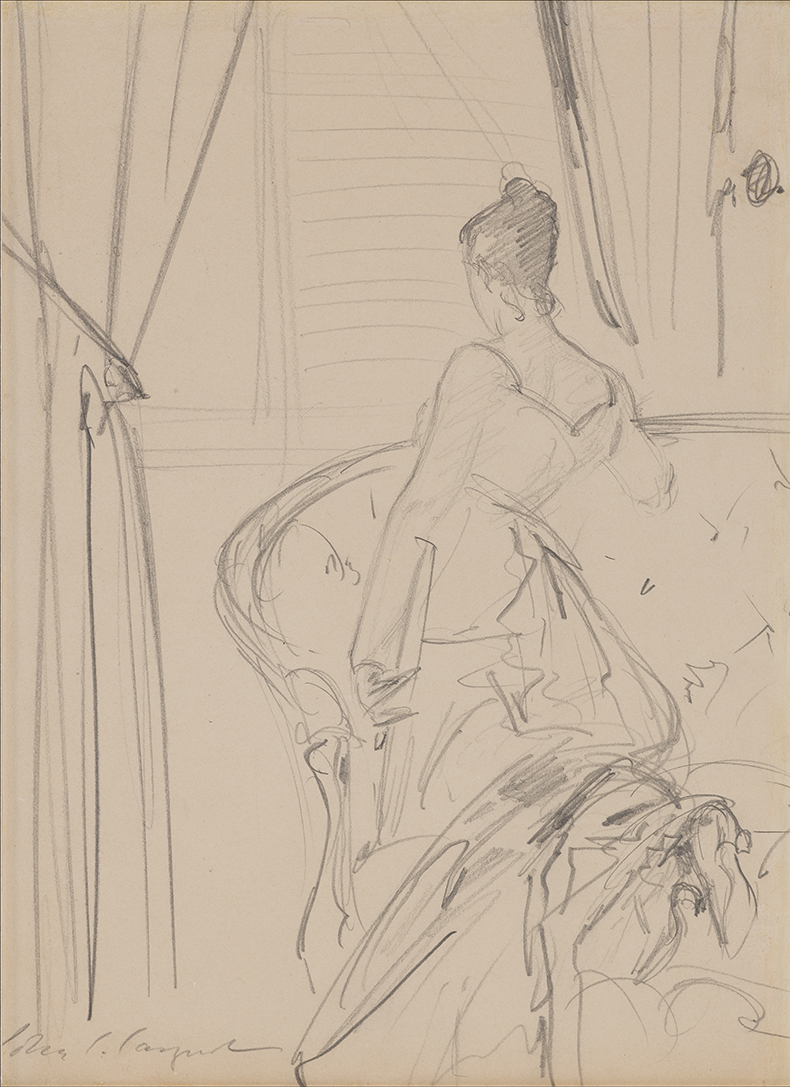

This work by John Singer Sargent is one of the many sketches of Madame Gautreau that he worked on in preparation for his once scandalous, now famous portrait Madame X (1884) – at least 10 sketches for this painting survive, the largest number known for a portrait by Sargent. Anything to do with the portrait of Madame X holds a certain fascination, not least because Sargent’s career almost died because of this project in Paris. It is also one of the most important drawings in the recently announced Eveillard gift, which has been promised to the Frick Collection. The way it sits within the story of the collection of Jean-Marie and Elizabeth (Betty) Eveillard illuminates the way the family collected art in the late 20th century. This is the very first drawing they bought and, surprisingly, it has a family connection. The donation of these works to the Frick also raises fascinating questions for understanding the collection. This drawing fills a lacuna that Frick himself had tried to – he appears to have desired a portrait from Sargent and he never got one.

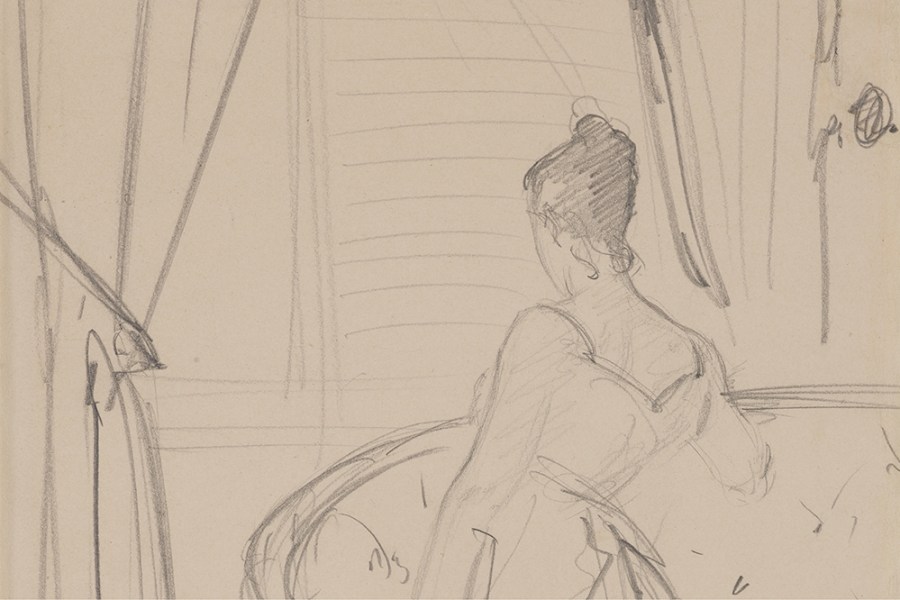

Madame Gautreau was a notoriously difficult subject. It was Sargent who wanted to paint her – something about her appearance really struck him and he was the one trying to find a way in. She was so socially engaged that it was hard for him to secure the sittings he needed with her. He thought that leaving Paris would be a good idea and he went to see her in Brittany, where she had an estate, but even there he had trouble getting her to sit for sufficient periods. He complained to his friends of her laziness. He wrote a letter to Vernon Lee where he remarked on the unnatural colouring of her skin because she powdered it a shade of purple. He says to Lee, if you don’t like coloured-up modern women, you won’t like my current model but she has the most beautiful lines. It is these lines that are really what he is capturing in the drawings, but in the Eveillard drawing she’s not even showing her face – it is all about the lines of her body. What this drawing contributes to the group of preparatory drawings – and they’re all different, either she’s lying back or she’s in different poses, but they don’t compete with the audacity of this pose where she is turned around with her ankles crossed – is the sense that he’s just trying to understand her body and space, hence those domestic furnishings, hence her uprightness.

Virginie Amélie Avegno, Madame Gautreau (Madame X) (c. 1884), John Singer Sargent. Frick Collection, New York (promised gift from Elizabeth and Jean-Marie Eveillard)

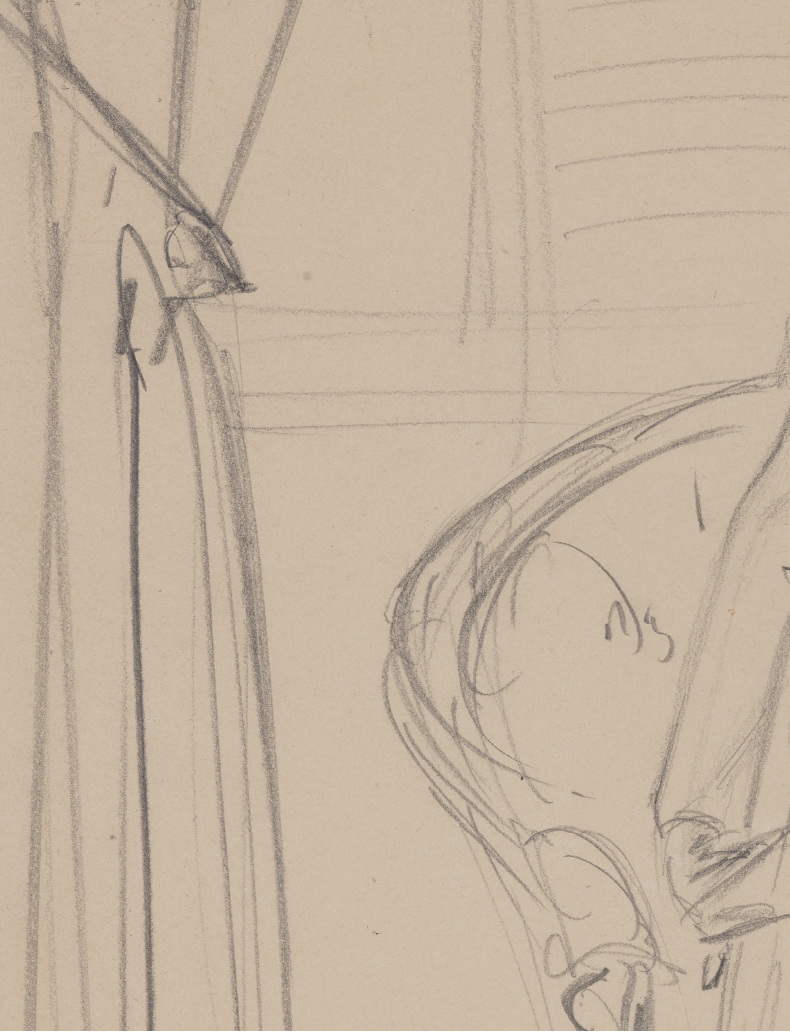

The Eveillard drawing, more than in any of the other drawings, gives a sense of the space she occupies, with that domestic furnishing of sofa, shutter and curtain, all of which disappears in the painting. If you compare it to the watercolour sketch of Madame Gautreau in the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard, you get a sense of the colours in this room that you can bring in to this sketch.

The Eveillard sketch anticipates the pronounced uprightness and the defined hourglass-ness of her body in the painting. A number of the other sketches show her just reclining, whereas this one cannot be simply preparatory for a front-on portrait. It is not thinking of composition; Sargent was truly trying to understand his model. It’s hard to imagine other portraitists preparing a portrait with studies like this, of the creature in space. While Whistler might have done it – he was known for his endless preparations and having models standing for him 40 times before he finished the work – even he had them strike what would be the final pose for those sittings. Here, it is an unusual practice.

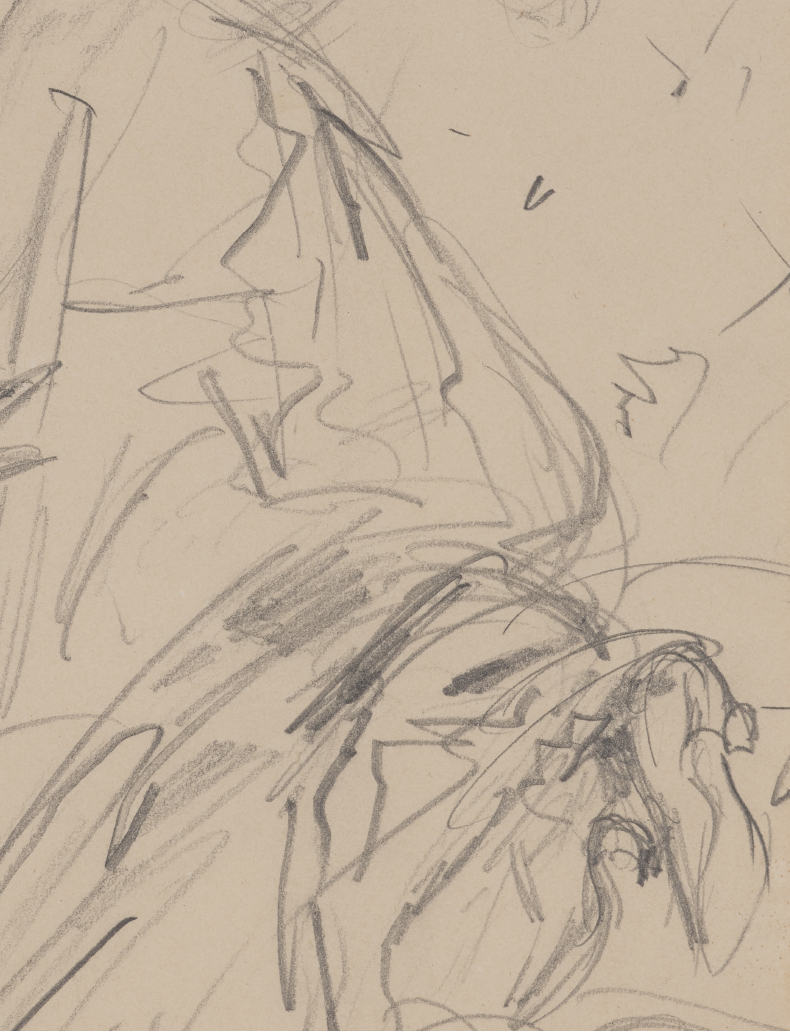

There is a lightness, a swiftness, to the marks on the paper. It’s very hard to make lines look light and, despite what many art historians say, it doesn’t necessarily mean that Sargent was quickly jotting it down. Even the crossed ankles, which might be awkward, are handled so deftly, despite the foreshortening of heels poking out. He’s really just trying to understand contours of her whole body. It’s a very studying, observing drawing – it’s not something where he’s trying to turn her into something else, it’s really trying to get her down.

Virginie Amélie Avegno, Madame Gautreau (Madame X) (detail; c. 1884), John Singer Sargent. Frick Collection, New York (promised gift from Elizabeth and Jean-Marie Eveillard)

On the paper, the curtains work almost as frame for her figure. They offer a little opening for her. And Sargent has included the shutters, where you can see the striations, but there is a part of the window that’s not shuttered and with it the idea that she could be looking out of the window to really give a sense of action in that domestic room.

The lines of the dress create the impression of a cascade down her back that you don’t see in any of the other drawings and certainly not in the final painting. I was a little surprised to learn that the dress had this detail on the back. It’s almost as if this view of her from behind shows her turning. It lends this drawing a dynamism that is less evident in the other portraits; it is as if she’s not locked there at all, as if that cascade is also moving with her legs crossing and uncrossing. There’s an agitation about Mme Gautreau in this moment.

Virginie Amélie Avegno, Madame Gautreau (Madame X) (detail; c. 1884), John Singer Sargent. Frick Collection, New York (promised gift from Elizabeth and Jean-Marie Eveillard)

The lost profile of Mme Gautreau is what is so compelling. The painting Madame X becomes so much about that nose, so much about that profile, but here, Sargent wants that profile to just disappear. He wants the rest of the body to speak and it gives her a chance just to be in her own thoughts. It’s as if she’s just looking out of the window, doing her own thing. Strangely, because we don’t see as much of her face, it gives her a more human moment, as if she is engaged in her own activity, not just posing for him.

The Eveillard collection shows a couple who were clear in what they wanted. The works they pursued are mostly figurative. They loved understanding artists like Sargent who were studying the human figure. They sought out the top works in each category for these artists; for Sargent poppies or a landscape would be beautiful – but he was best known as a portraitist, and they were looking for the finest in terms of figurative work. They predominantly collected preparatory or related works.

So it’s easy to see why they were attracted to this sketch when they bought it in 1975. This was a preparatory sketch to the most famous painting Sargent produced. But there is more to it than that. Betty Eveillard grew up in Boston. Her great-uncle, the portraitist Marvin Julian (1894–1986), also lived there. He was Armenian by birth but changed his name to follow the private art school in Paris where he studied, the Académie Julian. It was her uncle who taught Betty about Sargent. When he arrived in Boston he knocked on Sargent’s studio door and asked if he could get art lessons. Not only would he, among other things, get cigarettes for Sargent, but Sargent apparently would give him tips on how to do portraits. This sketch represents that personal history and, despite its famous pedigree, it is also a deeply personal drawing for the collection.

This work could be seen to resolve a disappointment for Henry Clay Frick as well. He is such a mystery man in some ways. We talk about what we know about him, but he left no journal, he left very little correspondence, and what letters there are are usually gruff and matter of fact. But we do have an undated letter from Sargent to Frick, probably from the first decade of the 20th century. Tantalisingly, we don’t know the response and we don’t know what prompted the letter. But the letter says, in effect, if the visit you want to make with me is about commission- ing a portrait, I’ve got to tell you I am not doing them any more. Here we see Sargent letting down Frick – not a man used to not getting his way – as gently as possible. Frick, of course, had portraits made of himself, and it is not beyond the realms of possibility that he was pursuing Sargent for a portrait. Whatever it was that he wanted, he didn’t get it. And while he was able to get his hands on a couple of small landscapes, which he gave as a gift to his lawyer, there is no portrait by Sargent in his collection. The arrival of this portrait by John Singer Sargent into the Frick Collection fills what we imagine to be that gap. It is a wonderful way to answer that longing, to salve Frick’s yearning. When visitors come to the Frick they, of course, see the works that he got. This work reveals the hidden personality of the collector by showing what he did not get and bringing into the light some of the absences, and at the same time revelling in the personality of the sitter and the woman who was instrumental in bringing the work into the Frick.

As told to Edward Behrens.

‘The Eveillard Gift’ is at the Frick Collection, New York, from 13 October–26 February 2023.

From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home