There is nothing to match the experience of entering Sir John Soane’s Museum in London for the first time. To walk through the door of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields and be confronted with the unfolding Tardis-like succession of spaces and walls studded with works of art and plaster casts is to enter into the mental world of its creator and first occupant. John Soane, architect of the Bank of England, Dulwich Picture Gallery, the Old Houses of Parliament (now lost), the houses of Pitzhanger and Moggerhanger, was both a classicist and an eclectic. His house museum is a testament to his zeal for collecting, his flair for spatial excitement and, in no little degree, to his wit. So crowded is the museum with ingeniously displayed artefacts that it is hard to imagine that this is only a small fraction of Soane’s entire collection. But only next door, in the third of the terraced houses that Soane acquired to accommodate his increasingly outsized ambitions, and unknown to most visitors, the Soane Museum’s library houses one of the world’s greatest collections of architectural drawings.

It would be impossible to put these all on public view. Architectural drawings are too delicate – the gentle washes of ink or watercolour that bring solidity and depth to these paper projects fade easily when exposed to light – and in many cases they are contained within bound volumes that it would be unwieldy to display. In any case, there are simply too many. At the time of his death in 1837, Soane had amassed a collection of some 30,000 architectural drawings. Many were made either by him or by his office, but still more were collected to satisfy Soane’s appetite to acquire masterworks by other architects.

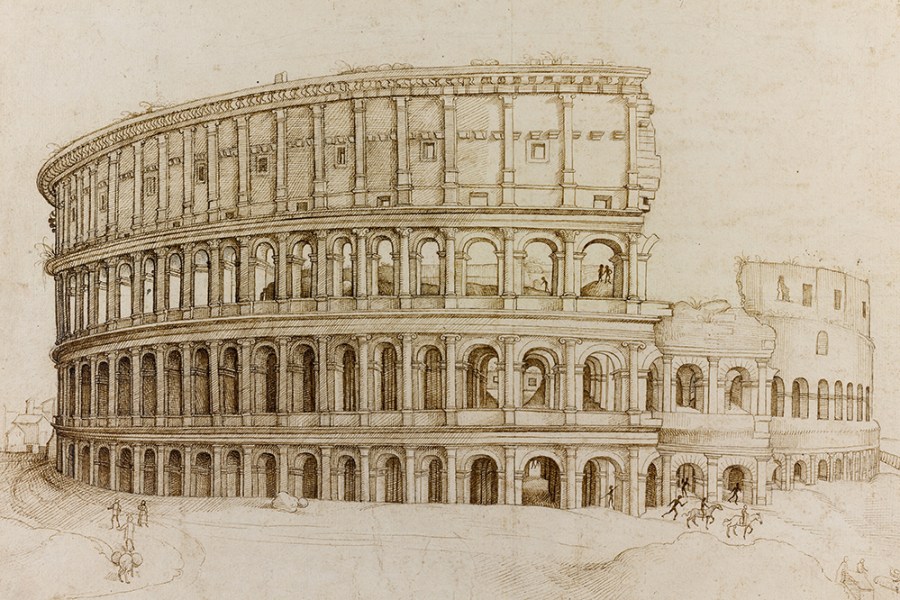

Capriccio (c. 1745–50) by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

It would take a book of many hundreds of pages to illustrate all of the drawings in the collection and the experience would overwhelm all but the most specialist reader (who could, anyway, turn to the museum’s excellent website). Frances Sands’s book deals with only a carefully curated selection of the collection’s most outstanding works – the ‘hidden masterpieces’ of the book’s title. As the Soane Museum’s curator of books and drawings, no one is better placed to make this selection than Sands and, by limiting the selection, she allows us to focus on the drawings themselves, each of which is interpreted with an insightful accompanying text and placed in the context of Soane’s collecting in a series of interpretative essays.

The examples that Sands chooses represent some of the finest architectural drawings ever to have been created. Examples range from John Thorpe’s design for Old Somerset House, said to be the first consciously classical-style building in Britain, to Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s moody and richly chiaroscuro drawing of the Temple of Neptune at Paestum, to the imaginative rendering of Soane’s Bank of England as though a ruin executed by his draughtsman Joseph Michael Gandy. Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor also feature, as too do John Vanbrugh, James Gibbs, William Kent, William Chambers, Robert Adam, Sir John Nash and Soane himself.

Unexecuted ceiling for the circular dressing of Harewood House, Yorkshire (1767), Adam office (Giuseppe Manocchi). Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Too often, architectural drawings are presented as dry artefacts, records of commissions that were never built, or of ambitious solutions of which architects were never able fully to convince their patrons. The real art, we are led to believe, is in the buildings themselves. Sands’s book, however, allows us to appreciate these drawings for the beautiful objets d’art that they are. Exquisite large-format colour photographs show each of these drawings to their best advantage and thoughtfully chosen details allow one to revel in their technical accomplishment. It is, in short, the closest that you could hope to get to sitting in the Soane Museum’s library out of hours and leafing through Soane’s most prized drawings.

As such, the book has a value both to the connoisseur, who will delight in the feast of technical mastery that is on display, and also to a more general reader for whom the detailed illustrations and Sands’s engaging and informative commentary serve as the perfect introduction to the art of architectural drawing. At a mere £35, this book is impossible to resist.

‘Architectural Drawings: Hidden Masterpieces from Sir John Soane’s Museum’ by Frances Sands is published by Batsford.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home