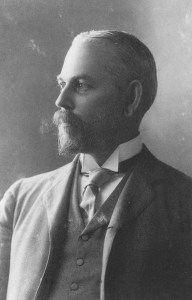

Among the last artists admitted into the 400-year-old lineage of the Kano family in Japan was an American called Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908). He was given the studio name ‘Eitan’ and was officially designated to authenticate paintings by writing certificates affixed with his seal. Fenollosa had arrived in 1878 to teach Western philosophy in Tokyo and, once there, he turned his energies towards the study and collecting of Japanese art. His mentors in this pursuit belonged to the last generation of Kano artists, heirs to the longest-lived dominant school of Japanese painting and the focus of a survey exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art this spring.

The Kano family lineage was started in Kyoto in the 15th century by Kano Masanobu (1434–1530), who mastered both the Song dynasty Chinese modes of ink painting and, with his subtle depictions of scholars in reclusion, the themes favoured by the military rulers of his day. His son Motonobu (1476–1559) succeeded to his post as official painter and secured the future of the Kano studio by instituting efficient workshop methods and a basic training system for students. A group of ink paintings by Motonobu in the exhibition feature a waterfall and cascade. They are now mounted as hanging scrolls, but were originally part of a larger suite of sliding-door paintings, as we know from a life-size copy of the originals. The life-size copy (mohon) was a part of the Kano apprenticeship – copying works by earlier Kano masters in order to learn and internalise their style and brush techniques. Once these were mastered, the artist could create his own variations. While he continued the ink-painting practices of his father, Motonobu also introduced the colourful subjects, such as flowers and birds, on a gold- leaf background that would become so significant for the Kano and their patrons.

Chinese Lions (late 16th century), Kano Eitoku. Museum of Imperial Collections, Tokyo

Motonobu lived and worked during a period of civil wars, with a series of strong leaders emerging by the mid 16th century. Among them was Oda Nobunaga (1534–82), who set the example for his successors by commissioning elaborate building projects and employing members of the Kano family to undertake the decoration of the castle interiors. The larger than life Chinese Lions by Motonobu’s grandson Kano Eitoku (1543–90) is believed to have been part of Nobunaga’s Azuchi Castle. The country was finally unified permanently under the rule of the Tokugawa shoguns, who established their power base in eastern Japan at Edo (modern-day Tokyo) in 1615.

In 1617 the Tokugawa in turn named Kano Eitoku’s grandson, Tan’yū (1602–74) as their first official painter-in-attendance in Edo to oversee the painted splendour that would bear witness to their authority

and wealth. Tan’yū’s work, like that of his contemporary Rembrandt in Europe, came to define the artistic Zeitgeist. He proved more than capable of fulfilling the shogunal mania for magnificence, creating vivid ensembles of hawks, tigers and landscapes on gold leaf (Fig. 1). Tan’yū expanded both the patronage base and the repertoire of the Kano. In 1641, he completed a set of paintings for the Abbot’s quarters at the famed temple Daitoku-ji, in Kyoto. Besides the Chinese-themed figural and ink landscape subjects that were standard fare since Masanobu’s time, Tan’yū turned to Japanese subjects such as the Tale of Genji. Tan’yū painted Mount Fuji in every format – on screens, hanging scrolls, albums and handscrolls. He was a pioneer in making ‘true view’ sketches of the mountain (Fig. 4), paving the way for artists such as Ike Taiga in the 18th century.

Bishamonten from Studies of Ancient Masters (Gakko-jo) (1670), Kano Tan’yu. Private collection, Japan. Photo: Morio Kanai

Tan’yū was also an avid collector of Chinese and Japanese paintings, which he copied and gathered in albums such as the Studies of Ancient Masters (Gakko-jō). The images often provided inspiration for creations by Tan’yū and his successors. The albums formed part of Tan’yū’s deep study of his artistic heritage, and served as tools for his work in authenticating paintings. The inscription on Eitoku’s Chinese Lions screen attesting to its authorship, for example, was added by Tan’yū. He also made thousands of quick sketches (shukuzu) of the paintings that he viewed. These were subsequently mounted as handscrolls, and provide invaluable visual evidence of the Chinese and Japanese art that was in circulation during the 17th century. Tan’yū established Kano dominance in the connoisseurship of paintings by creating certificates (kiwame) and inscriptions for the boxes in which paintings were stored.

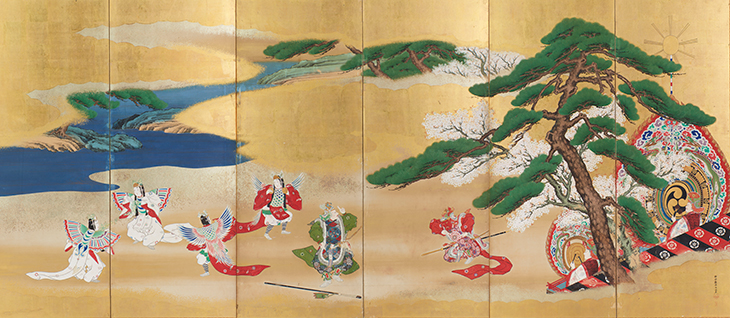

After Tan’yū was summoned to Edo, the artists of the Kano line that stayed in Kyoto, such as Kano Einō (1631–97), usually took the ‘Ei’ (of Eitoku) as part of their name. They often turned to subjects more closely related to the aristocratic culture of Kyoto, as is seen in the image of the courtly Bugaku Dancers by Kano Eigaku (1790–1867). The Kano influence remained significant in its original home, and as the military and merchant elite strove to emulate the shogunal and imperial example, Kano painters established a wide network of studios across the land.

Bugaku Dancers (mid 19th century), Kano Eigaku. Tokyo National Museum

The Kano further established their supremacy in the world of Japanese painting through their writings. In 1693 the Honchō gashi (Painting of the Realm) was published in five volumes as one of the first major texts on the history of Japanese art, with biographies of nearly 200 artists, along with their seals, and painting techniques. It was compiled by Kano Einō, and became the basis for the 19th-century publication Koga bikō (Notes on Old Paintings) by Asaoka Okisada (1800–56). This was the text on which Fenollosa relied in his research of Japanese painting authentication. Ironically, it was the Kano school’s loss of shogunal patronage that opened the door to Fenollosa’s entry on to the stage of Japanese art.

In 1867, the 15-year-old Mutsuhito ascended the Japanese throne as emperor, ushering in the period called ‘Meiji’ (enlightened rule), which lasted from 1868 to 1912. With the new emperor’s reign, often referred to as the Meiji Restoration, came many dramatic changes. Until then the de facto rulers of Japan had been the Tokugawa, military leaders who governed from Edo in Eastern Japan, while the figurehead emperor and his court resided in Kyoto. The shogunal rulers had successfully closed Japan to foreign countries from 1639 to 1854, allowing only the Dutch and Chinese restricted trade access through the port of Nagasaki. Several Western nations seeking fuelling stops and expanded markets for their merchants and missionaries attempted to open diplomatic and trade relations with Japan. Commodore Matthew Perry, sent by President Fillmore, succeeded in anchoring his ships off the coast at Uraga, at the entrance to Edo Bay in 1853, and in 1854 a trade treaty was signed by the shogunal government. This turned out to be one of the factors bringing about the downfall of the shogunate, as enemies of the shogun used the treaties as a rallying point for their political opposition. The last Tokugawa shogun abdicated in 1867.

Bishamonten Pursuing an Oni (c. 1885), Hashimoto Gaho. Philadelphia Museum of Art

With the new emperor, the imperial capital was moved to the former shogunal seat at Edo, and renamed Tokyo (‘Eastern capital’). The new leaders were determined to avoid any future repetition of the humiliation of Perry’s enforced treaties, and embarked on an ambitious programme of modernisation and industrialisation along European and American lines. To learn as much as possible as quickly as possible, two systems were instituted. One was to send Japanese students abroad to study specific aspects of Western technology, and the second method was to employ foreign professionals, yatoi, to work and teach in Japan. It was the latter programme that brought Ernest Fenollosa to Japan.

The remarkably long survival of the Kano was primarily owing to their status as official painters-in-attendance to the Tokugawa shogunate. With the overthrow of the shogunate the patronage base of the Kano collapsed and their studios and property, including their lands, were confiscated by the new government. At that point there were 19 official Kano studios in Tokyo. Some senior Kano served the new government in various capacities, such as teaching drawing at the Naval Officer’s School in the case of Kano Hōgai (1828–88).

It was in this time of turbulent transition and search for artistic identity among the Kano and other artists of the period that Ernest Fenollosa came on the scene to influence and be influenced by Japanese art in profound ways. His achievements in Japan were largely made possible through his close connections to Kano artists and to the intellectual elite, which helped him form his ideas about the preservation and continuation of the Japanese cultural heritage of brush painting. These were embodied by his contemporaries Kano Hōgai and Hashimoto Gahō (1835–1908) in their synthesis of Kano traditional painting methods with Western concepts about perspective and foreshortening. Fenollosa’s dream of a merging of the art of East and West did not survive the Kano experiments, but the revived Japanese painting style known as Nihonga which grew out of that effort continues even today.

Felix Fenellosa photographed in c. 1890. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Archives, Washington

The Kano-centered history of Japanese art that Fenollosa became heir to was transplanted to American soil. After his return to the United States, Fenollosa became the first curator of Japanese art in America

at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The collections in Boston, Philadelphia, and that of Charles Lang Freer, now housed at the Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C., reflect Fenollosa’s views. The holdings of the Philadelphia Museum of Art were from Fenollosa’s personal collection, inherited by his daughter Brenda Fenollosa Biddle and given to the museum. Fenollosa further influenced the field for decades with his two-volume Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art (1921).

In the heady days of Japanese Westernisation and modernism in the 1920s and early 1930s, however, the art of the Kano fell out of favour in both Japan and the West. The revival of interest in Japanese art for Americans after the Second World War was guided by the Zen world view of men like Daisetz Suzuki, who taught at Columbia University in New York. Collectors steered towards individualistic, eccentric artists, away from the orthodox Kano establishment; this seems unfair given that the Kano painters began with the same Chinese ink-painting tradition as the Zen painters. The first post-war large-scale exhibition of the Kano legacy was held at the Tokyo National Museum in 1979, and in recent years many aspects of the Kano tradition have been explored in Japan. It is hoped that this survey exhibition in Philadelphia, the first outside Japan, will bring new awareness of the genius and aesthetic contributions of the Kano to Japanese and world art. The time has come to give the Kano their due.

‘Ink and Gold: Art of the Kano’ runs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until 10 May.

From the March 2015 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home