The American fashion designer Herbert Kasper, commonly known as Kasper, has died at the age of 93. During his lifetime he assembled a significant art collection with a distinctive character, specialising in drawings – from the Old Masters to Anselm Kiefer – and 20th-century photography. A selection of these works were presented in an exhibition, ‘Mannerism and Modernism’, held in 2011 at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, where Kasper was also a life trustee. In 2017, Susan Moore visited the designer’s Upper East Side apartment to discuss the evolution of his collection, which began with a formative trip to Paris in 1953. The interview is republished in full below.

Kasper has somehow always managed to live the dream. Growing up in the Bronx before the Second World War, he fantasised about a bohemian life in Paris. In the mid 1950s, after his return from the City of Light, his first runway show gave him success as a fashion designer overnight. ‘It was like the understudy going on stage and finding themselves a star,’ he grins, eyes flashing in his expressive face. His first wife, the late Betsy Pickering, was a famous model and one of the most beautiful and stylish women in the world. He has certainly led something of a charmed life – one that, intriguingly, can be retold through the works of art he has collected with great thought and passion over the last six decades.

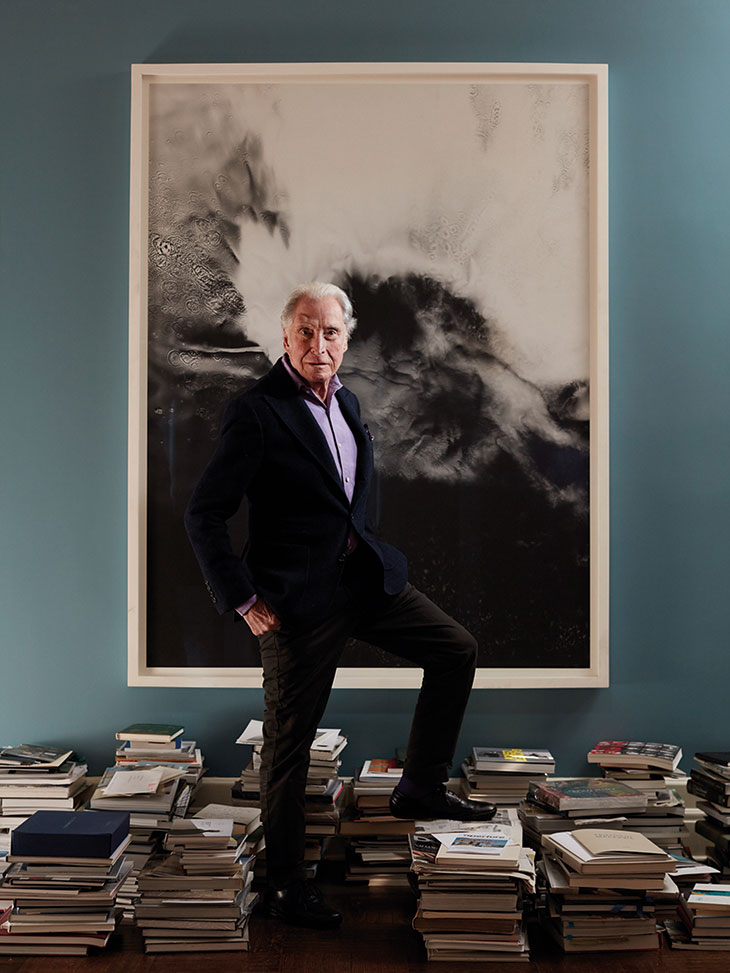

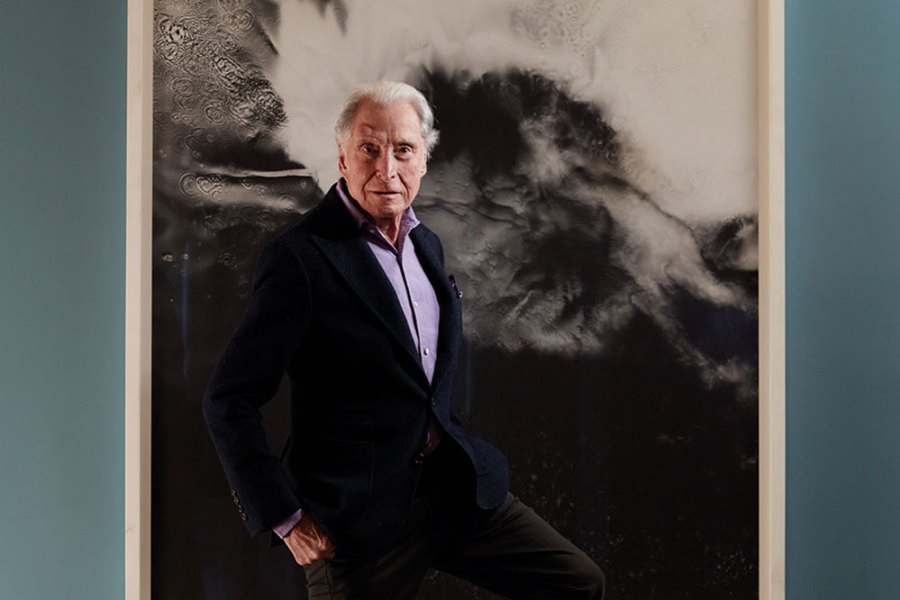

Kasper’s apartment, in an imposing building on the Upper East Side of New York, feels like another dream. The grandeur of a palace but without the formality, is how he describes it – words that might equally apply to the man himself. For Kasper – born Herbert Kasper, but known only by his surname – has an aristocratic mien, a confident stylishness enhanced by his aquiline profile and sweep of silver hair. His style, he says, is all about refined elegance and calculated casualness. When we meet in early spring, he is sporting a loose linen shirt in deep lilac and violet socks; he later tucks in the former and adds a jacket, instantly transformed for a portrait photograph. What is most striking about Kasper, however, is not so much the veneer as the keen intelligence beneath. He has a vitality and curiosity that belie his 90 years.

Kasper, photographed in his apartment in New York in March 2017, in front of an untitled photogram by Adam Fuss. Photo: Reed Young

His ever-expanding collection has three main constituent parts: Mannerist drawings, modern and contemporary works on paper, and photography. At first glance, this may seem an unlikely mixture, but there are all manner of visual and conceptual threads uniting the works. The collection is a coherent whole because it has emerged intuitively out of one distinctive, if evolving aesthetic sensibility.

On the morning we meet, Kasper is in reflective mode, musing about the nature of collections, and his own in particular. It was only when he was asked to write a preface to the catalogue of ‘Mannerism and Modernism’, the exhibition of part of his collection at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, in 2011, that he began to realise that the works of art with which he had surrounded himself were also his autobiography. ‘It is not so much about where I was or what I was doing, but what I was like at the time of buying something,’ he explains: ‘The collection is my eye, my instinct, and my learning.’ We are sitting on comfortable sofas in a room whose deep umber walls are lined with gilt-framed Old Master drawings, the two halves divided by an immense, floor-to-ceiling painting by Helen Frankenthaler. Hanging above the chimneypiece opposite, and sharing Frankenthaler’s vivid blue, is Words Going Round No. 3 (1985), a dry pigment and acrylic work on paper by Ed Ruscha. It seems a good place to talk about a collection that begins in the 16th century and ends in the present day.

The tale really begins with that trip to Paris, made in 1953, after Kasper had completed his studies at New York University and then at Parsons School of Design. It was at Parsons that his work caught the eye of the celebrity milliner ‘Mr John’, John Frederics, who offered him a job. To amazement, Kasper declined. He had arranged to study at the L’École de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne. ‘I had watched every movie about Paris made before the war, and every movie made after the war, and my idea of heaven was to live in a garret and eat baguette with cheese and wine. I did live that dream – so much so that I could not look at a Camembert for about 10 years.’ Frederics gamely sent him off with a list of introductions, and asked him to send back some designs for hats. One introduction was to the illustrator Maurice Van Moppès, who took Kasper up and introduced him to everyone, including Cocteau and his muse Jean Marais. ‘He was cultivated, and an intellectual, and I guess he was a bit of a mentor. He was a big collector, and he had a huge number of works by Constantin Guys. I’d never heard of the artist – he was a contemporary of Degas but not so good – and I must have been impressed because I bought one. I still have it.’

The hats, it turned out, offered another introduction. ‘I was not particularly interested in hats, and I started going to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and the Louvre to find inspiration. I went to the Old Master galleries because throughout history almost everyone has worn some kind of hat. It was a learning process for me. The Old Masters captured my imagination, and I became familiar with the shapes of that kind of painting.’ His heart and mind, however, already belonged to Picasso and Matisse.

His first major purchase was made in London, by an artist his 19-year-old self had dismissed as irredeemably bourgeois. After he had launched his own label in New York, he began to travel extensively, continuing to visit museums and look in gallery windows. One day in Cork Street he saw a Degas charcoal outline drawing, Study for a Dancer Adjusting Her Bodice (c. 1897), in the window of Victor Waddington’s gallery. ‘I fell in love with it. It was so beautiful – I had to have it. It was a big step as it was expensive for me at the time. After that, I started going to galleries more often and buying what I loved and could afford.’

He loved Picasso. ‘Am I a genius, am I original in choosing Picasso? It sounds so obvious but Picasso at his worst is better than most artists at their best. I collected Picasso and Matisse because those artists are good.’ Other early purchases included work by Dubuffet and a spare, cubist Ben Nicholson. In the 1980s came more cubists – Léger, Gris, and Picasso again. Most were works on paper. ‘If I am honest, at the time I didn’t truly understand the real beauty and importance of drawings, that they are so personal, the first thoughts of an artist. I bought them because I was smart enough to understand that I would rather buy the best in a drawing than a mediocre painting. So I stayed with drawings, and I feel quite pleased with myself about that decision.’

A display of Old Master drawings, including Baccio Bandinelli’s red chalk Head of a Woman Wearing a Ghirlanda (centre left) Photo: Reed Young

‘Drawings allowed me to buy works of art of the quality, originality and refinement that I wanted in all of my life. As a fashion designer, you are doing a composition in fabric, which is like doing a composition on paper or canvas. It is about eye, line and rhythm, and so are drawings.’ Sureness of touch and refinement of different kinds of line certainly characterise the group of works on paper surrounding the Degas study in the living room, from the sensual, soft pencil of Picasso’s Conversation (1926) and the robust, angular crayon of a reclining nude executed 40 years later, to the virtuoso pen and ink calligraphy of Matisse’s Large Nude (1935) and de Kooning’s bold graphite Five Women (1952), a relatively recent acquisition.

Kasper also began to look backwards. He had been looking at Old Master drawings for a while, mostly Dutch, as his second wife, Sandra Canning Kasper, was involved with the Mauritshuis. ‘I had looked at things, and been offered things, but not bought anything. There is a coldness about 17th-century Dutch drawings – they just don’t have passion.’ Then, at a dealer’s dinner in 1995, he saw Baccio Bandinelli’s beguiling red chalk Head of a Woman Wearing a Ghirlanda. ‘As soon as I saw this drawing, it hit me immediately, like a love affair.’ Soon afterwards, he acquired a panel painting of Christ falling under the Cross, with Christ ‘a voluptuous figure in red’, by another 16th-century Mannerist artist known as Nosadella. Given his attraction to these two works, Kasper decided to focus his attention on the drawings of this period.

It is perhaps hardly surprising that Kasper should have alighted on what the art historian John Shearman once dubbed the ‘stylish style’, in which the decorous harmony and balance of the High Renaissance gives way to elegant figures with exaggerated, elongated proportions and dramatic gestures, and to a nervous line that is no longer purely descriptive but often takes on a wild life of its own. In this collection, these qualities are exemplified in bravura works by the likes of Parmigianino, Perino del Vaga and Veronese.

The flowing, agitated line of Kasper’s five Perinos and the Veronese seems to spill out into the adjoining corridor to the Dubuffets, a meandering ink and gouache by Brice Marden and to a work by Adam Fuss that records the unexpected results of placing rabbit entrails on to Cibachrome paper. ‘I began to realise that what I liked about Mannerist art was that it signalled a departure. That was the same reason I had been attracted to cubism, and to photography. I am interested in periods of change, when artists are pushing forward the boundaries of art and new forms of expression are emerging.’

Kasper stands to show me how the large chromogenic print in the dining room by Edward Burtynsky, Shipbreaking No. 2, Chittagong, Bangladesh (2000), reminds him of the Nosadella Christ in its use of space. ‘What I also love about this photograph is that it is like looking at a Richard Serra, in terms of form and texture,’ he says. On an adjoining wall is Anselm Kiefer’s homage to the great medieval mathematician Fibonacci, a layering of gouache, acrylic and pencil over cut and pasted photographs from 2007. ‘I find it fabulous. It is a photograph which becomes a painting and which is also a drawing.’

Some 15 years ago, Kasper set himself a new challenge: ‘If you think you are so smart,’ he asked himself, ‘and you have such a great eye and such great intuition, why don’t you buy things that are happening?’ He started looking at contemporary art – and looking and looking. ‘The things that I liked had already happened or were things I was comfortable with, but the more I looked at photography I realised that here was an invention which I did not see in other areas.’ Although he had spent his life with photographs and photographers, it had never occurred to him to collect this material. He quickly became hooked. While he admired Diane Arbus, for instance, her work did not touch him – just as Pop art, as opposed to abstraction and minimalism, had not appealed in the 1960s. ‘I am not interested in reproducing life. I guess it is the originality of the photographer’s eye that appeals, a way of looking that makes something their own.’ This might be anything from photography that transforms its subject, such as a Brancusi image of one his sculptures, Leda, to the camera obscura experiments of Abelardo Morell.

It was during a visit to Vienna for a Parmigianino exhibition in 2003 that Kasper came upon a show of the photography of graffiti. ‘Until then, I’d never thought of my collage and ink Dubuffet in that way, but I realised that it belonged to that world and I began to collect photographs of graffiti’, he says. This included the likes of Man Ray’s photograph of a Max Ernst drawing in the sand, Brassaï’s The Imp, Belleville, Paris (c. 1952), William Klein’s Love Door (1955) and works by Helen Levitt and Aaron Siskind. Words play a part throughout this collection, in drawings as well as photography, works old and new. Inevitably, the Dubuffet also led to photographic collage – experiments such as Arnold Newman’s Barbershop Cutout No. 2, West Palm Beach, Florida (1940) – pure cubism – and Vik Muniz’s re-photographed collage version of a photograph from 1949 by Andreas Feininger, Noon Rush Hour on Fifth Avenue. It is this continuity of ideas that excites Kasper.

The phenomenal technical and visual innovations of Adam Fuss line his bedroom. To have his portrait shot, Kasper stands in front of a unique, untitled early photogram from a series made from splashed water reacting chemically as a flash of light that exposes the photographic paper. To make the splash, Fuss thrust his elbows into a barrel of water, and the unpredictable result has an eerily sublime quality. Other walls display a gelatin silver print photogram of a translucent christening gown from the My Ghost series and a 182cm-high pigment print of a chrysalis.

Books are in piles on the floor – in fact, there are books piled everywhere in the apartment, as well as neatly stored in the library bookcases. ‘To really know, you have to read and it takes a lot of time and patience – and you can’t know everything.’ That is why Kaspar has limited his acquisition of antiquities to just a few pieces, including the Roman marble Venus after a Greek original. ‘It is a shape, a form,’ explains the designer, who is so used to the silhouette as the definition of an idea. The figure also has a contrapposto stance worthy of any Mannerist draughtsman, and the consequent flow of the drapery is as much about line as form. ‘Look how this heavy, hard substance looks so delicate. What could be more beautiful?’

The living room in Kasper’s Upper East Side apartment, showing drawings by Degas, de Kooning, Picasso and Matisse, and (through the doorway) Léger’s Femme à la Toilette (1925). Photo: Reed Young

Kasper also enthuses about a white, minimalist work by the youngest member of the Japanese Gutai group, Norio Imai. It is a work of void, line, light, and shadows. ‘History may decide he is a great artist, or he may fade away, but this work says so much to me.’ Appropriately, it hangs beside the incised, abraded and punctured white blotting paper of a small Fontana from 1966–67. The living room is full of mostly monochrome works that are about ‘everything and nothing’.

They are also about formal parallels and resonances. For as much as Kasper’s collecting of art has been intuitive, his orchestration of the collection is decidedly artful. He relishes the angled, cut corners of Richard Serra’s black paintstick Canadian Pacific (1982) beside one of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s pale, poetical Colours of Shadow: C1209 (2006), which in turn is opposite the Norio Imai. Those same angles are apparent in a sculptural chair made of stone and metal tubes, near the marble Venus: ‘See how hard the stone is, but how it floats’. At the other end of the room is a Kiefer that has an applied sculptural addition in the form of a stethoscope. Kasper likens the display to putting together a fashion collection, which has to be both coherent and yet more than the sum of its parts.

Through a doorway, the vista culminates with the strict form – but burst of colour – of Léger’s Femme à la Toilette (1925). ‘For me it is the beginning and the end of my collection,’ Kasper. ‘It is from the most important period of a very important artist, and it is an icon. It took me a long time to be able to buy it – not in terms of affording it – but understanding that I had to. A collection is about building on knowledge gained.’

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home