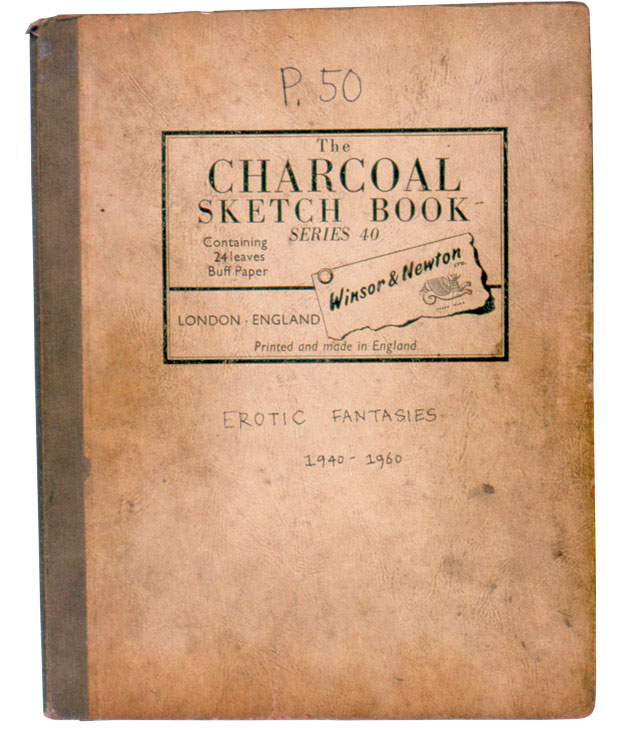

Over the course of 20 or so years, beginning during his time in the Non-Combatant Corps in the Second World War, Keith Vaughan (1912–77) made a number of sexually explicit gouaches and drawings which he later pasted into a sketchbook, labelling it ‘Erotic Fantasies 1940–1960’. He kept the album in his studio, where it was discovered after his suicide in 1977. More vividly executed than the hundreds of other erotic drawings left behind after his death, the images depict men engaging in various sexual acts including fellatio, anal sex, flagellation, and bondage. Vaughan’s executors didn’t want to destroy or separate them, but they found them difficult to offload to an institution in the anti-gay public atmosphere of the 1980s; art dealers were equally wary of handling such ‘specialised’ material. The images became, as the title of Gerard Hastings’ new book has it, ‘awkward artefacts’.

Eventually, in the late 1980s, the children’s publisher and art collector Sebastian Walker bought the entire sketchbook directly from the Vaughan estate. He was not to enjoy it for long, however, since he died in 1991 at the age of 49. When Walker’s art collection was auctioned at Sotheby’s in the same year, Vaughan’s ‘Erotic Fantasies’ – left unillustrated in the catalogue, and available to view only under supervision in a private room – sold for £44,000. They went into anonymous private hands and haven’t been seen since.

Recently, however, a set of photographic records, made in 1985 on behalf of Vaughan’s estate, were passed on to Hastings. He has seen fit to publish them for the first time. Awkward Artefacts contains illustrations of all 52 gouaches and drawings from the ‘Erotic Fantasies’. It also contains three short essays by Hastings about Vaughan’s work and sexuality, followed by extracts from Vaughan’s journals.

The book is the latest in Hastings’ series dedicated to various aspects of Vaughan’s life and work. As with the previous volumes, it’s generously produced and succeeds by foregrounding Vaughan’s own words and images; Hastings is intimately involved with the estate and uses Vaughan’s archive effectively. Coming on the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexual acts in England and Wales in 1967, and the 40th anniversary of Vaughan’s death 10 years later, it’s also a timely examination of Vaughan’s complicated sexuality, a mess of desire, secrecy, shame, and emotional frustration that was shaped in no small way by the oppressive laws of his time. ‘It is difficult to bear in mind that with all one’s honours, distinctions, successes etc, one remains a member of the criminal class,’ he wrote in his journal in 1965. The story of these images is a reminder of how painfully separate Vaughan kept his private and public lives and how gradually intolerance towards homosexuality dissipated during the 20th century.

Keith Vaughan’s notebook of ‘Erotic Fantasies 1940–1960’

Hastings admits to having been ‘initially overwhelmed’ by the ‘Erotic Fantasies’. It’s probably fair to say that they’re best not viewed on public transport. In translating his fantasies on to paper, Vaughan was undoubtedly titillating himself; these are all, to varying degrees, pornographic images. Tongues loll; whips are brandished; erect penises dominate the centre of each picture. But once the impact of their sexual content is absorbed, they can also be appreciated as satisfying studies of the male nude in various poses of tenderness, submission, vulnerability, and intimacy. Hands rest on shoulders; eyes meet; heads are bowed in reflection or tilted back in yearning. The gouaches, especially, are lovingly composed, with Vaughan’s khaki palette revealing familiar depths of unexpected colour. The final gouache, in which a naked young man places his hands gently on the head and inner thigh of an older man lying in front of him, his face gaunt and wasted, exudes all the sadness of Vaughan’s later years, in which he began to reminisce on youthful encounters and opportunities lost.

It becomes clear that these are emotional as much as sexual fantasies. Vaughan craved a meaningful and satisfying relationship his whole life. ‘Without it I do not think I can go much further,’ he wrote in 1939, in his first ever journal entry; in fact he was to go the rest of his life without it.

On a purely physical level he was able to fulfil most of his urges. Hastings provides a brief but fascinating account of Vaughan’s fitful relationship with Johnny Walsh, a young petty criminal who fitted Vaughan’s liking for ‘rough trade’ and at one point tried to blackmail the artist; in a journal entry from 1963 Vaughan describes a scene of mutual flagellation with Walsh in which the younger man cooperated ‘as a way of atoning for his sinful ways’. Emotionally, however, Vaughan lived in a state of frustrated isolation, squashed by his mother (who lived until 1976) and infuriated by his long-term partner, Ramsay McClure, with whom he fell in almost by accident in the 1950s and from whom he could never quite bring himself to separate.

In Vaughan’s publicly displayed work, the figures in his group portraits almost always stand in isolation. One thinks of the nine Assembly of Figures paintings he created between 1952 and 1976, a series of large-scale group portraits of mostly upright male nudes. These men may overlap, but they’re very rarely seen to be touching. In the ‘Fantasies’, by contrast, touch is everything. Only in sexual fantasy, perhaps, could Vaughan allow himself to conceive of human connection.

Tate Britain’s recent ‘Queer British Art: 1861–1967’ exhibition began with a lament about how many gay artists, before 1967, felt the need to suppress evidence of their sexuality. ‘This is a history punctuated by bonfires and dustbins,’ write the curators. It’s different with Keith Vaughan, in that we already have his long and candid journals, written with the explicit intention that they should be read by later generations. Now we can also view these graphic but poignant drawings and paintings. Given his meticulous nature and the carefully planned way he ended his life, Vaughan could easily have relegated them to the bonfire or the dustbin. We know he burnt other masturbatory images. The fact he didn’t burn these suggests that this most discreet of men was ultimately happy for them to join his journals in creating a record of his life ‘as complete & intimate & brutally honest as memory allows’.

Awkward Artefacts: The ‘Erotic Fantasies’ of Keith Vaughan, by Gerard Hastings (ed.), is published by Pagham Press.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home