In the early hours of 20 February 1913, Olive Wharry and Lilian Lenton broke into the Refreshment Pavilion at Kew Gardens, scattered some paraffin-soaked tinder around the floor and set the lot alight. As the wooden building burned, the two women – members of the suffragette movement – were caught running from the gardens by police, and subsequently did time (and hunger strikes) in Holloway Prison. Only 12 days earlier the same women had targeted three of Kew’s orchid houses, smashing glass panes and destroying some of the precious specimens inside (‘Queer way to get the vote!’ the director of New York Botanical Garden had written in sympathy to Kew’s then director, David Prain).

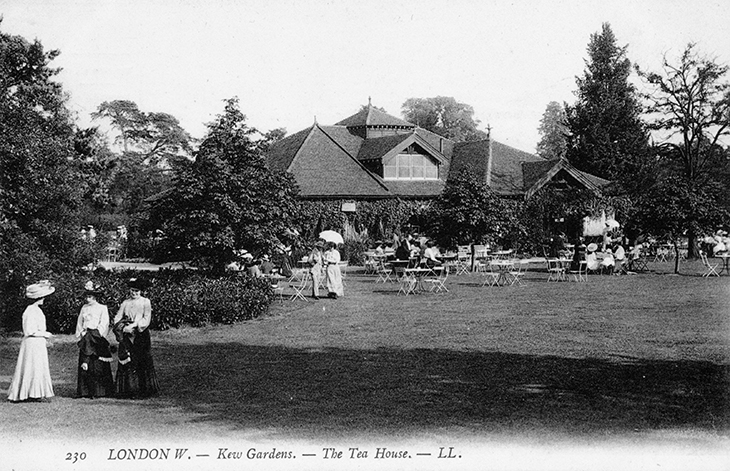

The Refreshment Pavilion at Kew Gardens, photographed before the fire of 1912. Photo: © RBG Kew

The chalet-like structure torched by the suffragettes had been built in 1888, a long-requested concession to visitors hitherto subject to the strict rules laid down by Kew’s second director (and Darwin’s great friend) Joseph Hooker: no smoking, no bath chairs or perambulators, no games, gymnastics or ‘military evolutions’ – and no picnics or luncheon parties. Located in the arboretum between the Marianne North Gallery and the Temperate House, the Refreshment Pavilion offered a ‘Shilling Tea’ with bread and butter, jam, cake and salad, or else a ‘Cold Collation’ of meats, cheese, veal-and-ham pie, bread and butter. After the arson attack a temporary structure was erected before a more permanent replacement was built in 1920. Kew’s archivists have unearthed some delicious examples of the British garden-goer’s character in the years that followed, including a complaint from 1965 that the pavilion’s cucumbers ‘were an unusual hue that was letting the country down’.

Yet another structure occupies the site today. Recently completed by Ryder Architecture, which has been involved in a five-year programme of works at Kew, the latest incarnation is a low-slung building of black steel and glass. Its obvious debt to East Asian architecture makes it a fitting addition to this corner of the gardens: from the restaurant’s large terrace can be seen the Chinese-style Great Pagoda, completed in 1762 and one of several buildings at Kew designed for Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales, by William Chambers. Kew’s meticulous labelling system makes any stroll here educational, and the Asian varieties in its 14,000-tree arboretum are plentiful – here a large-leafed Paulownia fargesii from China, for instance, or there the great gnarled trunk of the Japanese pagoda tree (Styphnolobium japonicum), planted at Kew around 1760.

When I visit in early September, some of the arboretum is already flecked with gold, as are the old vines growing on frames around the terrace, where I sit at one of many socially distanced tables. Kew announced the opening of its ‘brand-new food destination’ last summer – fiery pun unintended, presumably; but perhaps the original pavilion’s ashy fate inspired the new kitchen’s main selling point: a state-of-the-art Josper oven fed with DEFRA-approved charcoal and ‘woody waste’ from the gardens.

The Pavilion Bar and Grill near the Great Pagoda at Kew Gardens. Photo: © RGB Kew

The skin of my roast whole bream is certainly beautifully crisp when it arrives, though its slightly dry flesh would suggest it has had a little too much of the suffragette treatment. A generous sprig of rosemary comes, I assume, from the ‘chef’s herb garden’ on display at the other end of the terrace – as, hopefully, does the herb marinade for the spatchcock chicken also on the menu. Golden chips and a lime-dressed salad of quinoa and beetroot provide a pleasingly autumnal palette (and are probably the best things on the palate, too). With Kew horseradish vodka no longer on the menu, the vaguely botanical theme of my lunch continues with a brownie accompanied by matcha ice cream. Alas, a cafeteria-style system means that mains and desserts are brought all at once, after you’ve ordered and paid inside; by the time I have picked my way carefully through the fish, the ice cream looks more like pea soup than pudding.

People remember wistfully the days when entry to Kew Gardens was via a one-penny turnstile. Today’s entrance ticket leaves you little change from a £20 note, which makes paying £18.95 once you’re inside for a less-than-exemplary main course feel about as steep as the climb up the 10 storeys of the Great Pagoda. But Kew has been a target for government spending cuts for almost as long as the gardens have existed, and having lost an estimated £15m while its gates were closed this year by the pandemic, the institution is not set to receive any government support to mitigate the loss. That feels both ironic and tragic, given that the scientific work it does – think of its Millennium Seed Bank at Wakehurst, which has so far safeguarded some 40,000 of the world’s plant species – has surely never been more vital. Next time I visit the gardens, though, I might just risk the wrath of Sir Joseph Hooker and bring along my Tupperware. Cucumber sandwich, anyone?

From the October 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home