From the February issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

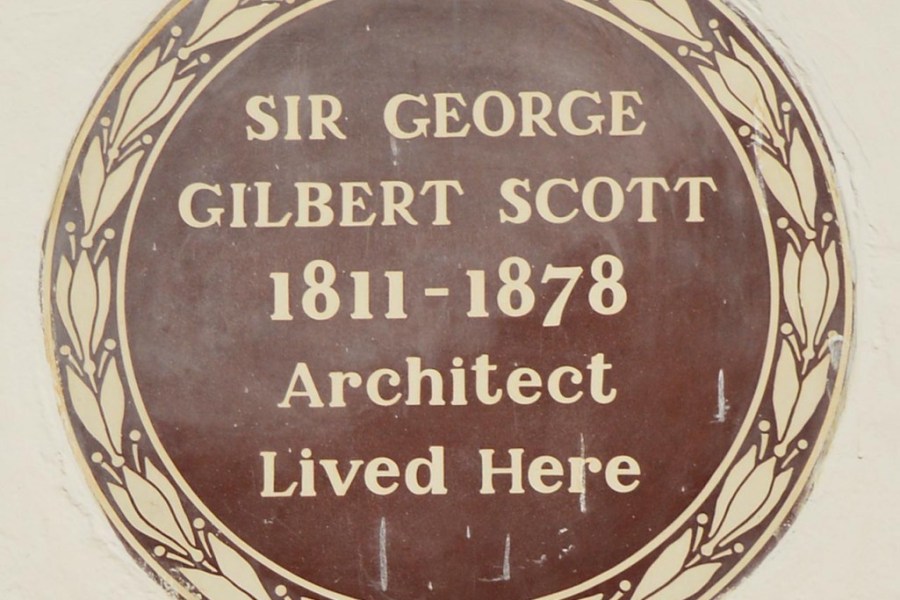

In 1903, unveiling the first commemorative ‘blue plaque’ to be installed on a house by the London County Council, the Earl of Rosebery, the former prime minister, observed that, ‘great cities gratefully remember those who have honoured them by living in their midst’. It requires imagination to bring the past to life. To learn that a battle was once fought where there are now houses, or to find a plaque on an office block announcing that, say, Charles Dickens lived in a house which once stood on the site, can mean little. It helps to have standing the actual building in which something important once happened, or a famous person once lived. We need the tangible, the authentic – which is why, in their absence, the town of Stratford-upon-Avon felt the need to conjure up both the birthplace and the home of the great national playwright whose quatercentenary is being celebrated this year.

London is peculiarly fortunate, for it has a scheme to mark the homes of deceased famous men – and women – which is 150 years old this year. In 1863, the radical MP William Ewart proposed in Parliament that there ought to be memorialised, ‘on those houses in London which have been inhabited by celebrated persons, the names of such persons’. The idea was taken up by the Royal Society of Arts, which set up a committee to make a list of those deserving ‘memorial tablets’ in 1866. The first to go up was on the house in Holles Street, Cavendish Square, in which Lord Byron had once resided. This no longer exists: despite the fact that one purpose behind such plaques is to encourage the preservation of famous residences, the house was demolished some two decades later. The oldest to survive today is now that erected in 1867 in King Street, St James’s, to record the earlier residence in London of Napoleon III – who was still alive at the time, so breaking the strict rule today that the subject of a blue plaque must be at least 20 years dead.

Blue plaques may be unique to London, but the marking of the homes of celebrities is certainly not confined to the capital. Bath has a similar scheme, while to walk down Rodney Street, Liverpool’s noblest, can be a history lesson in itself. Nor are the plaques in London necessarily blue, or round. Those honouring Byron and the French emperor were, but most of the other elegant ceramic plaques put up in the early days were brown terracotta in colour. And some were rectangular, and a few were classically composed bronze tablets – such as those fixed by the LCC to the former residences of Benjamin Franklin and Heinrich Heine in Craven Street, that miraculous Georgian survival overshadowed by Charing Cross Station. In fact, it is a pity today that the round blue ceramic model is invariably insisted upon, for a different treatment would sometimes be architecturally appropriate.

Chester House, Clarendon Place, the Bayswater home that Sir Giles Gilbert Scott built for himself in 1925–25 Photo: Gavin Stamp

Since the abolition of the Greater London Council in 1986, the blue plaque scheme has been administered by English Heritage. A few years ago, the ruthless budget cuts to which that organisation was subjected led to the suspension of the scheme but, happily, it has been revived – though it now depends on private donations to continue: they may be popular, ceramic plaques and the meticulous research behind their creation are expensive. There are now over 900 ‘blue plaques’ in London, whose histories can be found in Emily Cole’s magisterial volume, Lived in London: Blue Plaques and the Stories Behind Them (Yale, 2009). They are not all in places like Bloomsbury and Mayfair: finding one unexpectedly in a dreary and unlikely suburban location is one of the pleasures the scheme affords. The plaque commemorating Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, the man who saved Britain in 1940, was fixed to an Edwardian house in Wimbledon in 2000, so it is sad to have to record that the London Borough of Merton allowed it to be demolished a decade later.

Those thought worthy of commemoration reflect contemporary attitudes. In the early days it was mostly statesmen and writers – all men, of course – who were thought worthy. More recently, more women and members of ethnic minorities have been considered, along with famous foreigners who resided in London for a time. These days actors and musicians tend to dominate, but architects have always been honoured (several were on the original RSA committee). In this respect, what is curious is how little the houses chosen for homes or offices by successful architects expressed their stylistic preferences. Most Victorian architect blue plaques – G.F. Bodley, J.F. Bentley, J.L. Pearson, for instance – are fixed to ordinary Georgian houses, and even the hardest of Goths, like Butterfield and Street, seem to have been happy to live and work in the sort of buildings that, in theory at least, they despised. Grandest was the home of the rising George Gilbert Scott, who lived in the splendid Admiral’s House in Hampstead in the years around 1860.

Of particular interest are the handful of houses that were not only lived in, but designed by the person named on the blue plaque: those admirable and rare examples of an architect bravely living with his own work. The earliest example is that of John Nash, who, for a time, lived in one of his first houses in a stuccoed terrace in Great Russell Street (Vanbrugh Castle in Blackheath is of course earlier, but the residence of the great playwright-architect is marked by a private, not an official plaque). Then there is Norman Shaw, who lived in a quirky ‘Queen Anne’ house of his own design in Ellerdale Road in Hampstead, now enhanced with a blue plaque. The other examples are 20th-century architects. Sir Giles Scott, grandson of Sir Gilbert, built his own house in Bayswater – Chester House, Clarendon Place – in 1925–26. The architect of Liverpool Cathedral did not build in gothic, however, but in a refined neo-Georgian manner that very much reflected the taste of its time. The final example is post-war: the home of the architect Michael Ventris, better known as the decipherer of Linear B, the ancient script discovered at Knossos, which he designed with his wife Lois, in North End, Hampstead.

There are other famous and accessible homes of architects in London, of course, but a blue plaque on Sir John Soane’s Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields would surely be superfluous, while it would be difficult to find suitable wall space on the front of Ernö Goldfinger’s house in Hampstead. But why is there no blue plaque on the Tower House in Melbury Road, Kensington, the miniature castle designed and lived in by William Burges, the creator of Cardiff Castle for Lord Bute? After all, it is quite as distinguished as its neighbours, two studio-houses by Norman Shaw, both of which bear blue plaques in honour of minor Victorian painters, while Billy Burges was a most remarkable architect.

Click here to buy the latest issue of Apollo

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home