‘Women Look At Women’, the inaugural exhibition at Richard Saltoun’s new Mayfair space, opens with Renate Bertlmann’s extensive photo sequence Transformations (1969/2013). Appearing in 53 different images in various guises – posed, pouting, laughing – in a selection of different hats, sunglasses, and outfits, Bertlmann performs for the camera to poke fun at clichés about female identity. Paola Ugolini, the exhibition’s curator, sees in the work the seeds of the feminist art movement about to blossom. Bertlmann, Ugolini says, ‘was the first woman to dare to take a camera and auto-portrait herself. Ten years before Cindy Sherman.’ The work anticipates the proliferation of the ‘selfie’ mode in much contemporary feminist art.

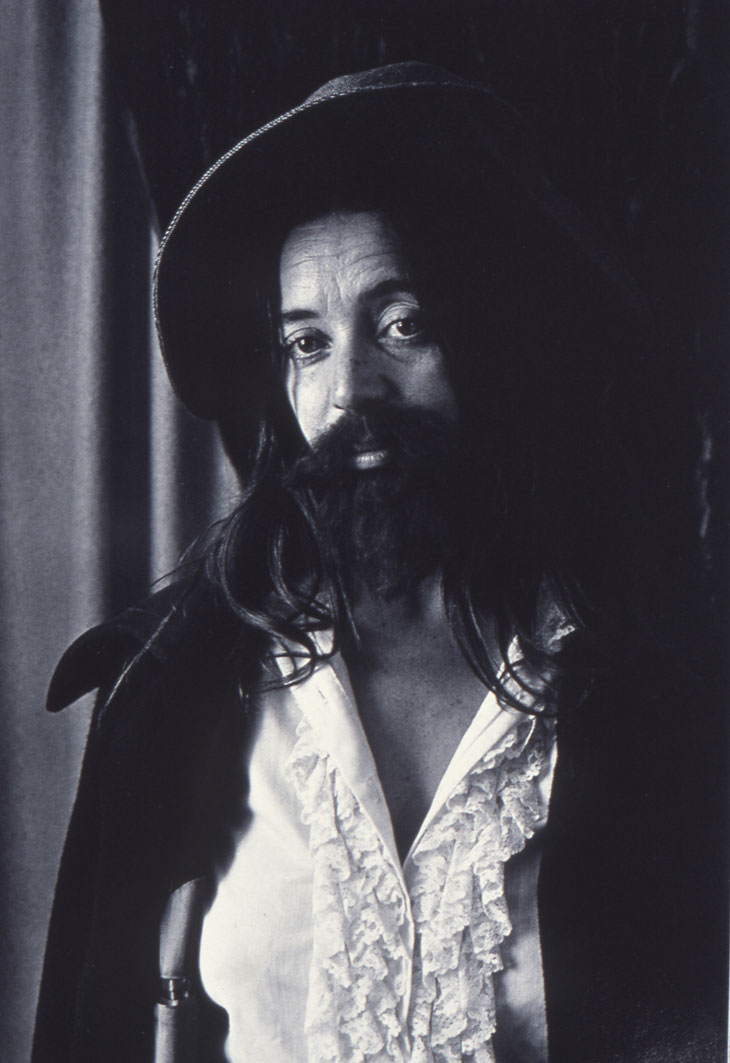

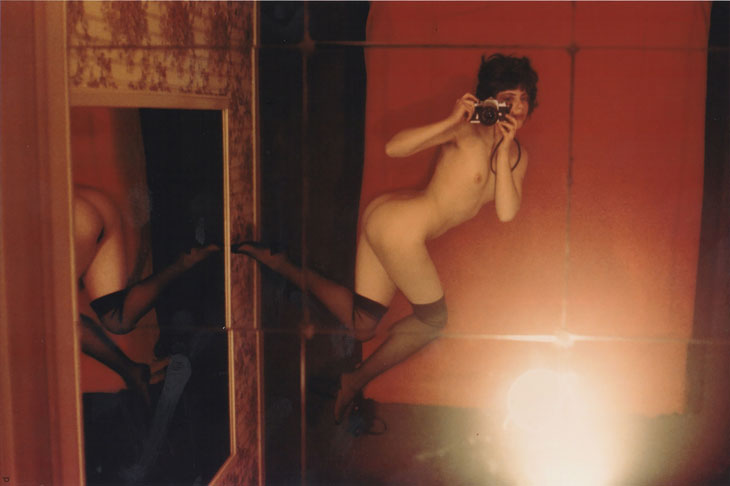

Throughout the exhibition, the use of the female body and its transformations are a conduit for artists working from a feminist perspective to discuss representation of gender and sexuality. Eleanor Antin appears in her bearded guise as the King of Solana Beach (Portrait of the King [1972]). Friedl Kubelka performs the role of the soft-porn erotic model, posing in black stockings, leg cocked, her large camera positioned in order to obscure her face (Pin-up [1973/74]). Helen Chadwick stages a contemporary memento mori image: the artist’s body arranged like a statue on a plinth, naked but for the cross pendant hanging from her neck, her hand resting on a skull (Ruin [1986]).

Portrait of the King (1972), Eleanor Antin. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery; © the artist

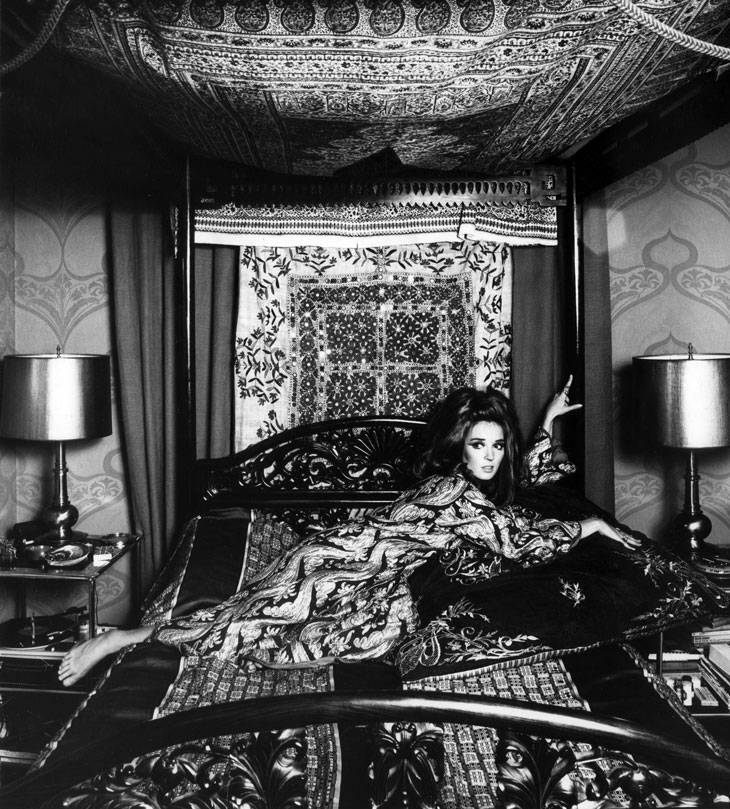

When asked why she always used her own figure in her work, Francesca Woodman replied: ‘It’s a matter of convenience. I am always available.’ Two Woodman photographs bookend the exhibition. In Early (1972–75), her naked torso is pinched with clothing pegs, an unflinching representation of flesh as artist’s medium. This photograph is cropped, and as with much of Woodman’s oeuvre, her face is obscured. Similarly, in Untitled (from the Swan Song series) (1978), Woodman hides herself under an animal skin, the fur converging with her naked form. An amusing counterpart is Rose English’s Jo and Tail (1974), in which English’s collaborator appears centaur-like, her arched back fusing seamlessly with a horsetail. The levelling of human and animal skin in Woodman’s tableau stands in contrast to the proliferation of fur worn by the women in Elisabetta Catalano’s photographs from the late 1960s and early ’70s. Catalano’s portraits of artists, actors and society figures – Monica Vitti, Sharon Tate, Talitha Getty – represent a fashionable, commercial vision of ‘beautiful’ women. Here, fur and other luxury fabrics signal glamour, wealth and status.

Talitha Getty (1968), Elisabetta Catalano. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery; © Archivio Elisabetta Catalano

In addition to casting light on the relationship women have with their own bodies, the exhibition explores how female artists have encountered the bodies of other women. But it is difficult to not see in Catalano’s images an element of what other artists in the exhibition were fighting against. Placed directly opposite Catalano’s photographs, Jo Spence’s Body Parts (1978) fragments the artist’s body into individual slides. The black and white images depict the body in extremis, made both abstract and abject: a fissured tongue, the dimpling around the areola, dry skin on two sets of toes. These fragments question notions of the classical, contained, and regulated female ideal. In Putting Myself in the Picture, written in 1986 after her cancer diagnosis, Spence would write openly about the psychological consequences of living in a culture full of images of idealised female forms: ‘I realised with horror that my body was not made of photographic paper, nor was it an image, or an idea, or a psychic structure […] it was made of blood, bones and tissue.’

Inspired by Bertolt Brecht, and the working-class, socialist community she was engaged with in East London, Spence’s politicised, confrontational style was designed to be both pedagogic and emotive. There are references to the topic of labour in other works in the show, notably Alexis Hunter’s Xerox series Secretary Sees The World (1978) and Kubelka’s Tagesportrait: Lore Bondy am 9.8.1976, 7:30 – 22:15 (1976), which depicts the domestic routine of the artist’s mother. While questions of class might be implied, racial politics are completely absent. Each of the 13 exhibited artists is white. This is not to negate the historical significance and continued relevance of these artists’ work. Still, it is uncomfortable to see an exhibition of feminist art – claiming to consider multifarious representations of, and by, women – isolated from contemporary, intersectional politics.

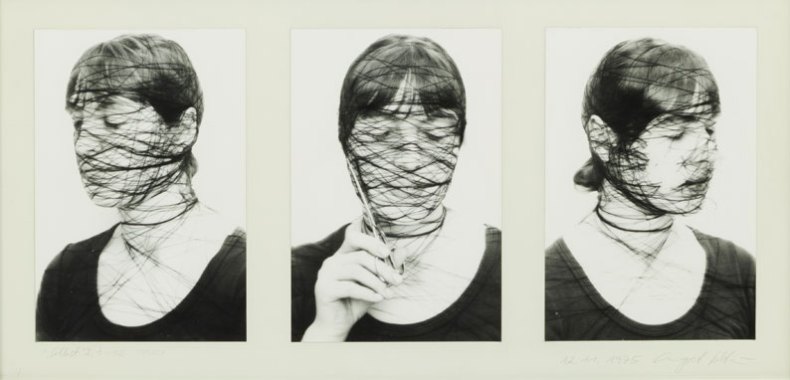

Selbst II, 1-12 (Self II, 1-12) (detail; 1975), Annegret Soltau. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery; © the artist

The show ends on a powerful and defiant note with Annegret Soltau’s Self II, 1–12 (1975). Soltau spun threads around her face, slowly tightening them to the point of disfigurement and pain, and using a pair of scissors to cut herself free from the tangled web. The images provide a metaphor for much of the work in the exhibition, invoking freedom and oppression, life and death, clarity and obscurity, joy and pain.

‘Women Look at Women’ is at Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, until 31 March.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home