In September 2000, Christie’s called up the Oxford historian of Islamic science Emilie Savage-Smith. The auctioneer wanted to show her an unusual manuscript. The covers were scruffy, badly fitting and disfigured by bird droppings. But inside were 48 sheets containing 14 unique maps and an unknown treatise. After much detective work Savage-Smith and her co-author Yossef Rapoport, who teaches at Queen Mary University of London, concluded that it was a copy made around 1200 of the Book of Curiosities, which is originally dated to between 1020 and 1050. Most likely written by a smart man at the Egyptian Fatimid court, it is one of the most important Arabic manuscript discoveries in the last century – amply worth the £400,000 the Bodleian Library paid for it in 2002.

The authors have taken their time but in Lost Maps of the Caliphs they offer a comprehensive and fascinating appraisal of the manuscript, putting it in the context of other Arab and world maps. Remarkably, the Book of Curiosities contains the earliest world map annotated with the names of cities – 395 in all. It contains the earliest recorded use of the word ‘Angle-Terre’ (Inqiltirrah) to identify England. It also has an early version of the circular world map that adorns later editions of al-Idrisi’s Book of Roger, which was commissioned by Roger II of Sicily in 1138. Drawing on late antique and Byzantine sources, the Book of Curiosities is the Fatimid missing link connecting the competing Islamic and non-Islamic cultures clustered around the Mediterranean.

The authors have taken their time but in Lost Maps of the Caliphs they offer a comprehensive and fascinating appraisal of the manuscript, putting it in the context of other Arab and world maps. Remarkably, the Book of Curiosities contains the earliest world map annotated with the names of cities – 395 in all. It contains the earliest recorded use of the word ‘Angle-Terre’ (Inqiltirrah) to identify England. It also has an early version of the circular world map that adorns later editions of al-Idrisi’s Book of Roger, which was commissioned by Roger II of Sicily in 1138. Drawing on late antique and Byzantine sources, the Book of Curiosities is the Fatimid missing link connecting the competing Islamic and non-Islamic cultures clustered around the Mediterranean.

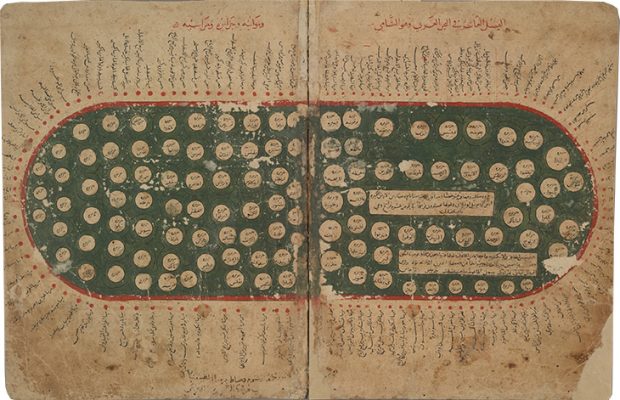

The maps depict both the Earth (the ‘Laid-Down Bed’) and the Heavens (the ‘Raised-Up Roof’). In the unpolluted skies of medieval Cairo, 3,000 stars were visible to the naked eye. There is a splendid illustrated list of 11 comets identified by Ptolemy. My favourites? The Mane of the Horse, with twin flicks of light trailing behind it; the thick and wavy Long-Bearded one; and the Skewer, tapering to a sharp edge as it zooms across the sky.

Such comets were portents that ‘revealed the workings of the Universe’, write Savage-Smith and Rapoport, ‘and, if properly understood, heralded events on Earth’. Deception is, according to our medieval author, ‘one of the most inauspicious and ill-omened’ comets, its rectangular shape a precursor of the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Ripper, represented as a large star with six rotating round it, is said to have heralded a rebellion against the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim in 1005–07. The science of the stars was taken seriously as a way of navigating the future.

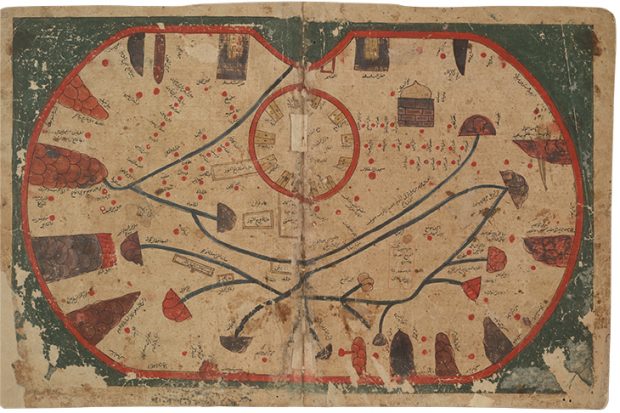

Map of the Mediterranean Sea in ‘The Book of Curiosities’ (MS Arab c. 90) (copy from c. 1200), Egypt. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

Rather than being designed for earth-bound navigation, the maps of Fatimid Egypt and its environs are decorative and descriptive. Think of them as visual aids – a bit like a PowerPoint presentation. The map of the Nile with its parachute-shaped mountains is not based on original cartographic research; rather it is a variant of one made by the ninth-century Persian polymath al-Khwarizmi (Algorithmi). Nonetheless, Coptic informants tell the author that the Nile floods because the summer sun melts the snow on the mountains – ‘an explanation that is as close to the actual Nile system as ever been achieved by medieval Islamic scholarship’.

The map’s creator tells us that he spoke to ‘trustworthy sailors’, ‘wise merchants’ and ‘ships’ captains’. The beautifully designed oval Mediterranean map is packed with circle-shaped islands and harbours – Tyre and Acre are good, we are told, but avoid Sidon. Comparable is the simplified square map of Cyprus, labelling 25 of its ports, while also giving the lowdown on the island’s exports.

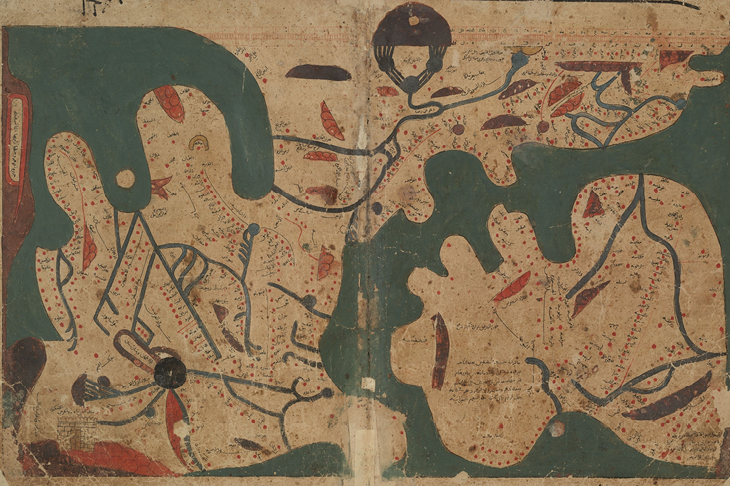

Naturally, the most attention is paid to Fatimid possessions. The orange-green map of Sicily marks the ‘strong, tall and impregnable’ walls of Palermo and the onion-domed palace of the ruler, symbols of imperial power in an island that regularly changed hands between Muslims and Christians. Mahdia, now a Tunisian resort, was an important Fatimid domain. The Book of Curiosities represents it by showing three landmark buildings, palaces of the imams who founded the city. It’s a bit like a postcard of London illustrated with the Shard, Big Ben and St Paul’s. The description of the port of Tinnis in the Nile Delta includes an interesting account from the market inspector, one Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Bassam, who lists the city’s inns, the measurements of the main mosque and even estimates the population based on how much bread it consumes.

What makes these maps and the accompanying information so important – and indeed poignant – is that by the time this copy was made in 1200, the Fatimid empire had been destroyed by Saladin on his way to defeating the Crusaders. Sicily had already been taken over by Roger II, and soon enough Mahdia and Tinnis would fall into oblivion – the latter is completely lost. The distinctive Shia Ismaili caliphate of which the Book of Curiosities is a product now gave way to the Sunni Ayyubids, whose focus naturally tended more towards Damascus and Jerusalem.

Map of the island of Sicily from the Book of Curiosities (MS Arab c. 90) (copy from c. 1200), Egypt. Bodleian Library, Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

Savage-Smith and Rapoport have done a splendid job in rescuing this intriguing work, forcing us to reorient our sense of the geographical priorities of differing Islamic dynasties. As they write, this is ‘a hybrid map for the hybrid early Islamic culture, at home with the Greek legacy of the ancients as it was with its imperial present’. Notably there is little overtly religious here – the Prophet is quoted only once. Nor is it especially scientifically advanced. Its importance lies therefore outside the debates over the golden age of Islam that bedevil our discussions of medieval Muslims. Its value is more anthropological. It asks us to think ourselves into the world view of an educated man curious about his empire, keen to show off the knowledge he had picked up here and there – both in written form and, when he needed to clarify, in a diagram or map.

As the authors tantalisingly tell us, there are tens of thousands of Arabic manuscripts lying in libraries unread. Who knows what other treasures might be out there – and how they might reframe our view of the Islamic past.

Lost Maps of the Caliphs: Drawing the World in Eleventh-Century Cairo by Yossef Rapoport and Emilie Savage-Smith is published by the Bodleian Library/University of Chicago Press.

From the May 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home