In late 1516, at the age of 64, Leonardo da Vinci left Italy for France. He came at the invitation of the young king François I, an ardent admirer who said of him: ‘No other man born in this world knew as much as Leonardo.’ He was granted an annuity of 1,000 écus, and a handsome manor house at Amboise in the Loire valley. He died there on 2 May 1519.

A year before his death a visitor to his studio saw three paintings – The Virgin and Child with St Anne, St John the Baptist, and a portrait of ‘a certain Florentine lady’ which was doubtless the Mona Lisa. These late masterworks now hang in the Louvre, together with two earlier paintings from his years in Milan – The Virgin of the Rocks and a portrait of a Milanese woman, probably Lucrezia Crivelli. This is the largest single holding of Leonardo paintings in the world, representing something between a quarter and a third of his total output (unresolved questions of attribution make the exact number of his paintings debateable). The largest collection of Leonardo’s surviving notebooks is also in Paris, just a few hundred yards from the Louvre, at the Institut de France. Their presence has no connection with Leonardo’s twilight years in Amboise, however: they were seized from Milan’s Biblioteca Ambrosiana during the Napoleonic invasion of the 1790s.

In Italy there has long been a feeling that France has laid claim to more than its fair share of ‘Maistre Lyenard de Vince’ (as he appears in contemporary French documents), and in the run-up to the Louvre’s quincentennial exhibition this old and rather pointless grievance resurfaced. The Italian government, then dominated by the ultra-nationalist Lega party, threatened to embargo all loans to the exhibition. Things were eventually smoothed over at presidential level, but of the various Italian loans exhibited only two are Leonardo paintings.

The Madonna of the Yarnwinder (c. 1500–01(?)), Leonardo da Vinci and workshop. Photo: © Bridgeman Images

Another conspicuous absence is the Salvator Mundi, much hyped in advance as the star of the show. Though apparently destined for the Louvre Abu Dhabi when it was sold in 2017 for a record-breaking $450m, it has since disappeared from view. According to current rumours, it may be aboard Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s yacht, or it may be in a high-security lock-up in Switzerland. Either way, it’s not in the Louvre. When I ventured to mention this to the exhibition’s co-curator, Louis Frank, he said with a shrug, ‘As a painting it is not important.’ I took this to mean that, like many experts, he is doubtful of its attribution to Leonardo. The exhibition features another version of the Salvator Mundi (privately owned; formerly in the collection of the Marquis de Ganay). The catalogue attributes it to the ‘workshop of Leonardo’, and refers somewhat vaguely to a ‘prototype’ which was ‘probably designed’ by Leonardo.

Though diminished from its original conception of definitiveness, the exhibition is full of wonders. It includes four of the Louvre paintings (the ‘Florentine lady’ has not deigned to stir from her glass-fronted boudoir in the main gallery, and so must be visited separately). Also present are St Jerome from the Vatican Museum; The Musician from Milan; the charming Benois Madonna, which was in Paris in the late 19th century but is now in the Hermitage; and two renditions of The Madonna of the Yarnwinder (the Buccleuch version, stolen from Drumlanrig Castle in 2003, recovered in 2007 and now in the Scottish National Gallery; and the privately owned Lansdowne version with a landscape background similar to that of the Mona Lisa).

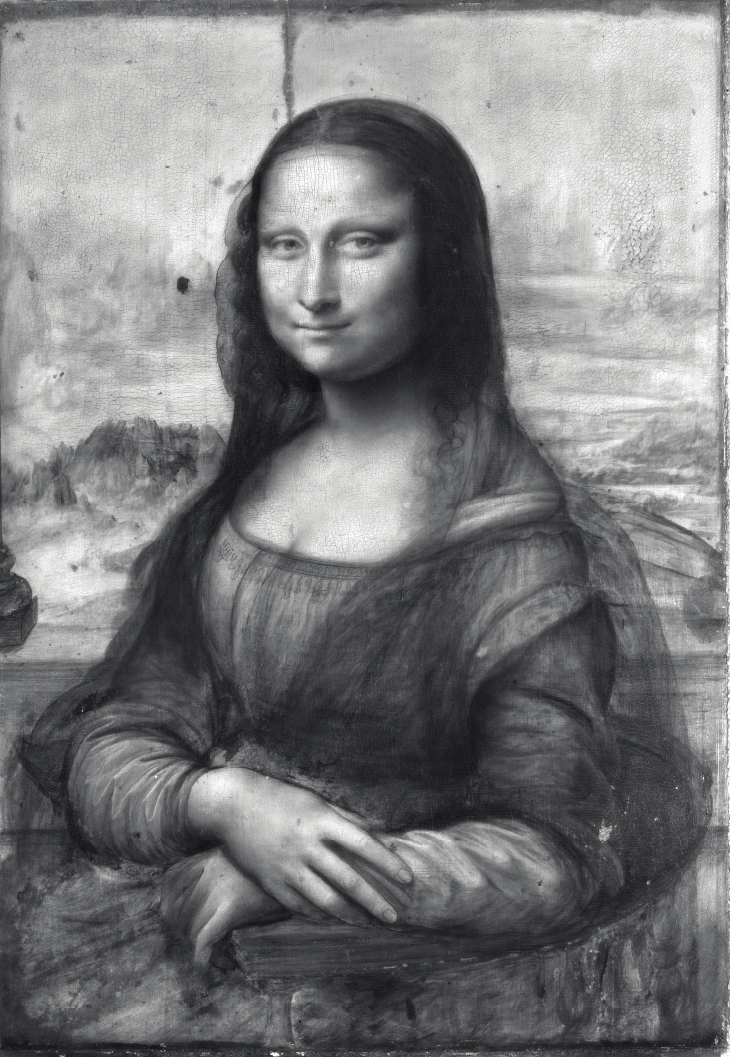

Untitled-2 Infrared reflectogram of the Mona Lisa. Photo: © C2RMF/Elsa Lambert

An exciting innovation is that each of these paintings is accompanied by an infrared reflectogram. These rather ghostly monochrome images reveal the underdrawing beneath the paint surface, and recover many details that were changed or discarded in the final execution of the painting. One notes with a frisson the slight alteration of the fingers of the Mona Lisa’s left hand – this pentimento shows up on the reflectogram as a blurring, almost as if she’d moved just as the camera clicked. There are also revelations about the original conception of the Madonna of the Yarnwinder. The underdrawings of both versions exhibited show traces of a much busier composition. In the background is a donkey, perhaps alluding to the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt, and there are vestigial traces of a domestic scene involving the infant Jesus being placed by his mother into a sort of baby-walker which Joseph has constructed. This group reappears in an anonymous 16th-century version of the painting – a fascinating insight into the complex genealogy of this much-copied work.

The exhibition also provides a scholarly account of two lost works on which Leonardo was working in Florence in the first decade of the 16th century – the weirdly erotic Leda and the Swan, known only from copies; and the Battle of Anghiari, an unfinished mural in the Palazzo Vecchio, later covered over with frescos by Giorgio Vasari. Two large copies of the Anghiari mural, made before its demise, show a savage balletic melee of snarling soldiers and terrified horses.

The Virgin and Christ Child with a Cat (c. 1478–81), Leonardo da Vinci. Photo: © the Trustees of the British Museum

The paintings are famous and charismatic yet also strangely aloof: they inhabit their own meticulously formulated world. It is his drawings that buttonhole you, particularly the informal sketches with their rapidity and wit – what he called componimento inculto (‘intuitive composition’). Here is the joyous series, in leadpoint and brown ink, featuring a mother and child with a cat. They were done in the late 1470s, and prove to be a gestation of the Madonna and Child in the Uffizi Adoration of the Magi. A tiny sketch of the same period has a different kind of immediacy. It shows a hanged man – Bernardo di Bandino Baroncelli, the assassin of Giuliano de’Medici, executed at the Bargello in Florence in December 1479. This grim piece of reportage was probably intended to be worked up into a painting – both Verrocchio and Botticelli produced propagandist paintings in the aftermath of the conspiracy. Beside the drawing he carefully notes the clothes Bernardo wore – ‘small tan-coloured berretta […] blue coat lined with fox fur […] black jerkin with the collar covered with stippled velvet’.

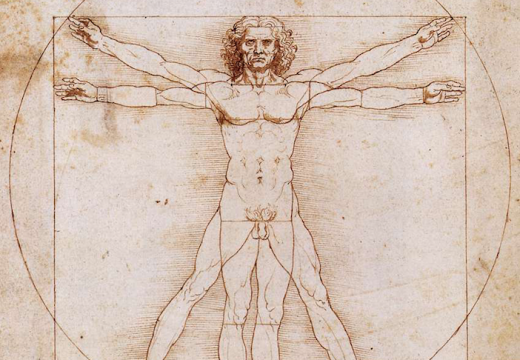

Also redolent of Leonardo’s presence are the dozen or so notebooks, packed with the astonishing variety of his interests – geometry, architecture, anatomy, botany, meteorology, lenses, shadows, whirlpools, and of course the flight of birds, applicable to his perennial dream of human flight. Some of them are pocketbooks no bigger than a pack of playing cards – an eyewitness account of Leonardo mentions a ‘little book he had always hanging at his belt’. These workaday objects, with their grubby vellum covers, are as close to him as we get.

‘Leonardo da Vinci’ is at the Musée du Louvre, Paris, until 24 February.

From the February 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home