The Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) in Paris is housed in an early 18th-century mansion in the historic Marais district. With generous exhibition space, it is also home to a huge collection, a library, and a conservation workshop. Its director Simon Baker arrived in 2018 from the Tate Modern. For its current show, ‘Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy’, he has drawn on the collection of the MEP and added loans to create an exhibition about love that includes the work of established and respected image-makers such as Nan Goldin, Nobuyoshi Araki and Sally Mann. So far so institutional. The premise of the exhibition seems at first glance entirely unthreatening. It even features cartoony pink hearts on some of walls and in its publicity materials. Even so, I can’t help finding it subversive for posing tricky questions about photography, privacy and love.

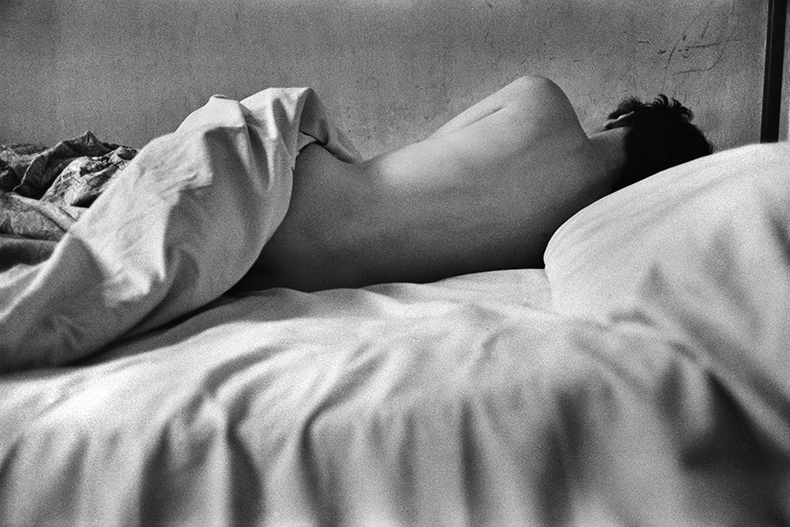

From L’Oeil de l’amour (1952), René Groebli. MEP, Paris. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Esther Woerdehoff; © René Groebli

Baker writes in the catalogue that researching ‘Love Songs’ stirred up memories of making mix tapes for beaus. The show is divided into Side A and Side B, the former featuring work made between 1950–2000; the latter between 2000–20. The oldest series is Rene Groebli’s L’Oeil de l’amour (The Eye of Love), an elegant view of his honeymoon that must have seemed daring when he took the photographs in 1952; the Araki works on show, Sentimental Journey (1971) and Winter Journey (1989–90), are (mostly) tender images of his wife, not his more controversial work depicting Kinbaku, the Japanese art of bondage. Even so there’s an image of Yoko while they’re having sex, her head pushed back on the bed.

Also in Side A, Herve Guibert captures his lover Thierry smiling over a glass of wine, or sexually aroused, or in the bath; Alix Cléo Roubaud photographs herself with her husband, sometimes naked or half-naked or wearing stockings and suspenders. Emmet Gowin’s wife is shot standing up, dress raised, urinating on a barn floor. The selection of work by Nan Goldin and Larry Clark recording their respective milieux seem relatively tame by comparison. As I walk round, some of the images by other photographers make me to wonder if I should be seeing it at all.

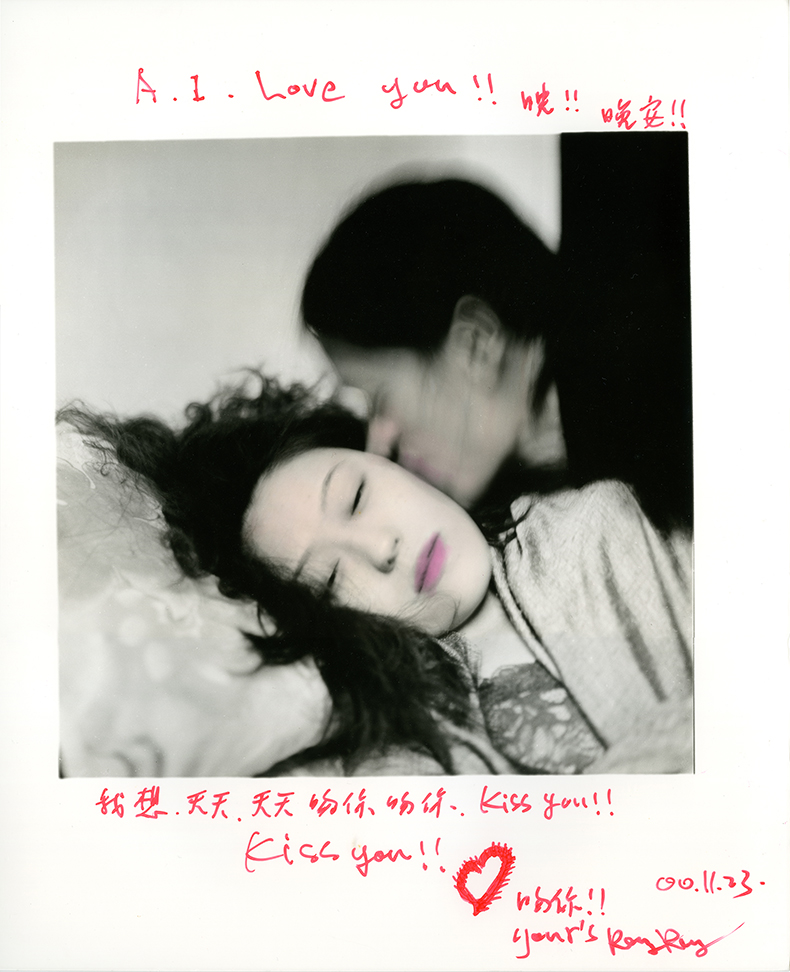

From the Personal Letters series (2000), RongRong&inri. © RongRong&inri

Things get more raw on Side B, upstairs with younger image-makers showing themselves having sex (JH Engstrom and Margot Wallard), or their mothers having sex (Hideka Tonomura) or their ex-wives undressed (Leigh Ledare, shooting his ex-wife alongside current husband). Sally Mann’s portraits of her ailing husband stand out for their sheer warmth, as do RongRong&inri’s photographs of each other. In their series, Personal Letters, each print is inscribed with the couple’s notes. They took the photographs when they were together then, when forced to part, scrawled these love letters to each other and mailed them. But, again, I come back to the question: why am I seeing such personal work?

It’s a question tacitly acknowledged by the gallery, whose website carries a warning that some of the images ‘can hurt the sensibilities of the visitors’; in his catalogue essay Baker accepts that his alternative, intimate history of photography risks ‘setting artist and viewer at odds’. However, he adds that it might also be ‘so rich and rewarding for both’. The title of the essay, ‘Love Songs: A New Objectivity’ suggests what some of the reward might be; it nods to the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement in Germany in the 1920s (currently the subject of a show at the Centre Pompidou) and the embracing of unsentimental reality. People have always had partners, why does that have to be private?

For some of the artists in ‘Love Songs’, those for whom the personal is political, their work is a refusal to feel shame over being gay, or old, or a desiring woman, or for having an affair, or for wanting their spouse. Lin Zhipeng’s frank images of youths, for example, can be read as a blow against conservative China, a country in which artists have long used the body as a site of resistance. More broadly, the personal, subjective nature of these images a challenge to external, objective authority.

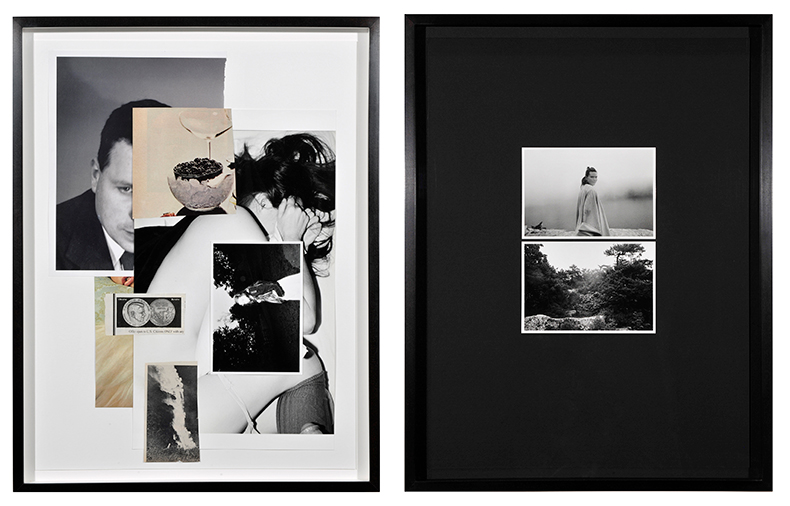

From the Double Bind series (2010), Leigh Ledare. © Leigh Ledare

The sheer variety of scenes on display makes it impossible to classify them neatly; it even makes individual bodies of work hard to pin down. Leigh Ledare’s Double Blind (2010) is a case in point. Mounting the images of his ex on a black background and those taken by her current husband on white, he lets viewers ponder the difference between the two series – and whether photography is indeed capable of registering it. Ledare also splices some images with cutouts from vintage porn magazines – a more intimate way of viewing a faked kind of intimacy.

Intimate images outside galleries are actually pretty common, it seems to me. ‘Love Songs’ might be described as presenting a typology, in that all the artists here are photographing the same thing. The achievement of the exhibition, however, is to prove that they’re not showing the same thing at all.

‘Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy’ is at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, until 21 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home