From the January 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Scrawled on the door to Maggi Hambling’s Suffolk studio are the words ‘Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood’. When you consider Hambling and her work – the roiling sea paintings, the penetrating portraits, her War Requiem series – it comes as no surprise that she confronts the making of it with something akin to a battle cry. But those Shakespearian lines also seem an apt exhortation for an artist who has, on occasion, had to suffer the slings and arrows of public indignation and media broadsides.

I’m visiting her at home in a small village near Saxmundham, less than a week after the official unveiling of her sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft in east London. ‘Yes,’ Hambling says grimly, ‘I thought that subject might just touch upon our conversation…’ The work now standing on Newington Green is the result of a 10-year campaign, spearheaded by the journalist Bee Rowlatt, to give the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) what is, extraordinarily, her very first monument anywhere, in the place where she set up and ran a school for girls. Hambling’s sculpture, a silvered-bronze mass of female forms culminating, at its very top, in a nude figure intended to represent a kind of Everywoman at the birth of a movement, was greeted with wails of moral outrage in a response out of all proportion to the 747 people who responded to a public consultation about the monument back in 2018.

Hambling’s sculpture For Mary Wollstonecraft (2020), installed on Newington Green, London, in 2020. Photo: Ioana Marinescu

Having been in Suffolk since England’s second lockdown was announced, Hambling has not yet seen the sculpture in situ. But it frustrates her that so many of her detractors have not seen it in the flesh, and that the majority of photographs published in the press cropped out most of the sculpture to focus on the diminutive nude figure at its pinnacle. ‘That does rather get to me,’ she says, preparing coffee at a paint-spattered sink perilously close to what she wryly calls ‘the most hygienic lavatory in Suffolk’. The mise en scène that is the loo’s immediate surroundings could be a portrait-of-the-artist-through-objects: framed photographs of much-loved deceased dogs, a cartoon of Hambling in front of one of her Wave paintings, and an overflowing gold ashtray in the form of a scallop. Stuck to the window above, an image of the Queen gives the royal wave to Hambling’s three hens scratching around on the lawn outside – Maya Angelou, the Honourable Tufty, and Henrietta.

Through the door, the studio floor is littered with fag ends – as much the necessary detritus of work, for this artist, as the surplus paint encrusted on the walls. Hambling herself – in black puffa jacket over thick grey woollen jumper, baggy black jeans above red trainers, her shock of grey hair framing that famously fierce, blue-eyed gaze – looks ready for a skirmish. As she explains, her ‘statue’ was never going to be anything approaching conventional. ‘Its title is for Mary Wollstonecraft – the vital word that nobody can read, apparently… Somebody compared her to a sort of space rocket of hope, I quite like that.’ But she didn’t have an inkling that commemorating a pioneer of feminism with a nude figure might be badly received? ‘The minute you do someone in historical dress it belongs to history, it’s not now. And the battle for women’s rights is by no means over, is it?’

The kind of feminism that would rush to cover a nude female figure with a T-shirt, as happened within a few days of the sculpture’s inauguration, is not the kind that Hambling understands (though I imagine she would have found the face masks and black gaffer tape that temporarily turned the sculpture into a caped crusader rather witty). ‘There’s more and more puritanism about, isn’t there?’ she says, lighting what will be one of many Marlboro menthols with a performative snap of her Zippo. ‘Oh gawd…’ Some of the negative responses in the media have clearly disheartened her – but not for long, I suspect. ‘I went to Waitrose last Wednesday afternoon – I’m politically against Tesco – and I was approaching the exit with my trolley and one of the lovely jolly ladies in there gave me a big grin and said, “Been making trouble again…” Hah! That’s the sort of remark that keeps you going, isn’t it? Fuck all this art-world nonsense.’

As that encounter attests, Hambling is no stranger to what she calls ‘a fuss’ over public sculpture. In 1998 A Conversation with Oscar Wilde was installed near Charing Cross Station. Her monument to the writer, one of her heroes, depicts his head and arms rising out of a sarcophagus-like slab of granite, apparently mid-witticism. ‘It was very important to me that he wasn’t on top of a tall plinth – he was a man of the people, he was a great humanitarian, and so I wanted him on our level, where you could sit and have a chat.’ There is, as in much of Hambling’s work, perhaps a hint of a self-portrait here. The fact that the bronze bust seems to embody in three dimensions her distinctively vermicular style – that it was so very Hambling – was too much for some critics at the time, with Tom Lubbock in the Independent even encouraging its vandalisation. And vandalised it was, with Wilde’s cigarette snapped off or sawed through three times to date (though Hambling suspects this to be the work of ‘some anti-smoking loony’).

Hambling’s The Scallop (2003), installed on Aldeburgh beach, Suffolk. Photo: © Andrew Dunn/Wikimedia Commons (used under Creative Commons licence [CC BY-SA 2.0])

Five years later came Scallop on Aldeburgh beach, her giant bronze memorial to Benjamin Britten, who lived in the seaside Suffolk town for 30 years. Unlike Wilde’s and Wollstonecraft’s, this sculpture was not a public commission, but a project Hambling conceived of and fought for herself. That, too, provoked a wave of hostility that seems hard to understand in hindsight. ‘A certain newspaper at the height of the fuss about Scallop reproduced a big picture of it,’ Hambling remembers. ‘“Nobody wants it, it’s got to go.” Ten years later in the travel section of the same newspaper, “Where to go in England” or whatever, and there’s the good old Scallop, biggest photograph in the middle, “Come to Aldeburgh…fish ‘n’ chips…” I think it takes people a bit of time…’ Time will tell whether the sculpture for Wollstonecraft will see a similar sea change in opinion. If one thing is certain, it’s that many more people have now taken an interest in Wollstonecraft than would have been the case had a less challenging work been made in its place.

The trouble at Newington Green has overshadowed what is for Hambling a milestone exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery in London (closed 23 December 2020). Simply titled ‘2020’, the show marks her 75th birthday – also honoured with a BBC documentary which aired in October – as well as, of course, a year that will be bookmarked in history as an annus horribilis. One of the first of 37 oil paintings encountered in the exhibition is Self portrait (angry), made at the very beginning of England’s first lockdown. ‘I was going to show something in New York,’ Hambling explains, ‘and then… one’s life is suddenly totally out of control, and I was furious, like anybody else. Not being able to see other people, hugging friends and the rest of it […] Heaven knows why it had that effect, there’s always uncertainty, isn’t there? We fool ourselves that we know what’s going to happen in six weeks’ time, but of course we don’t.’

Young dancing bear (2019), Maggi Hambling. Courtesy Marlborough Gallery; © Maggi Hambling

Although made up of work from the last three years, the show is a retrospective of sorts: it has afforded Hambling the opportunity to look back at her 60-year career and join the dots. All the long-running themes are here in these new paintings: death, war, sex, laughter, the sea. A large room in an upper floor of the gallery is given over to a series of works dealing with the human impact on the natural world – most of them focusing on a particular animal: an elephant missing a tusk, a polar bear floundering in melting ice water, a chained dancing bear. In Rhino without horn, Hambling can trace a direct line back to one of the first things she ever did at Ipswich School of Art, in 1963 – an ink drawing of ‘Rosie’ the Indian rhinoceros in Ipswich Museum. ‘I really think of that as my first portrait,’ she says. ‘It was the first time I’d used ink, which was very challenging and exciting, and it was my portrait of Rosie. Although of course she’s stuffed, she’s dead, I was trying, looking into her eyes, to make her as alive as possible.’

Rosie, the stuffed rhinoceros in Ipswich Museum (1963), Maggi Hambling. British Museum, London. © Maggi Hambling

Born in Suffolk in 1945, Hambling grew up in the market town of Hadleigh – within walking distance, as it happened, of Benton End, where Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines (known as ‘Lett’) were running their art school. That it was ‘notorious for every vice under the sun’ was perhaps part of its draw for the 15-year-old Hambling, who, in a bid to show her parents she was serious about being an artist, set off for the house one summer’s evening with her first two oil paintings under her arm. She describes showing the pair her work as Morris had supper at the end of a long table: ‘Lett was bringing him dish after dish, and couscous – who the fuck had couscous in England in 1960? […] Lett said, “I suppose you’re still at school, you’d better come along in the holidays.” And I did, the very first morning; and then life really began.’

After Ipswich, Hambling attended Camberwell School of Art, studying under the painter Robert Medley, and then the Slade, where she had a short-lived but obligatory flirtation with conceptual art. Even then, her beloved Old Masters had a habit of creeping into her projects. For Rembrandt (1970), Hambling attached 30 plastic bags to railings outside King’s Cross, each containing a photocopied detail from the Dutch artist’s erotic print The French Bed. They all disappeared in a matter of minutes, she claims, courtesy of passing London cab drivers. (Rembrandt, too, is credited for why she has never gone near a computer: ‘What I suspected would happen was that somebody would sit there and tap in “National Gallery” and then tap in “Rembrandt”, and up would come some little reproduction – and they’d think they’d seen Rembrandt! So that was that for me.’)

An opportunity to work cheek by jowl with the Old Masters came in 1980, when Hambling was the National Gallery’s very first artist in residence. It was only by making detailed charcoal studies of works such as Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ and Rubens’ Samson and Delilah, she has said, that she gained a better understanding of paintings she had previously thought she knew ‘backwards’. Those six months gave her, too, an introduction to a public audience, and vice versa, when every Wednesday afternoon she would open up her studio to visitors, answering questions about her work in a paint-streaked white coat. A few years later, Maggi Hambling as a ‘personality’ was beamed into the nation’s sitting rooms via the new Channel 4’s Gallery, an art-history game show hosted by George Melly. Each week the two team captains – the art historian Frank Whitford and Hambling, looking very Wildean, cigarette in hand, vodka in her glass, and on one occasion sporting a fake moustache – were joined by celebrity guests and art students as they were presented with paintings to identify.

By this time, Hambling had made the first of a kind of portrait that would lead Melly, who became a close friend, to dub her Maggi ‘Coffin’ Hambling. Frances Rose was one of her neighbours in Battersea – ‘this great old girl who used to sew bells on to the bottom of a pair of long red knickers for the old people’s party’ – and Hambling had painted her several times from life. Later on, she was with her when she died. ‘That experience,’ she remembers, ‘I couldn’t get it out of my system, and so a friend said, “Well why don’t you paint it, that may help.”’ The resulting portrait from memory is one of exquisite tenderness and power, recalling something of Rembrandt’s most vulnerable self-portraits.

Frances Rose IV (1975), Maggi Hambling. Arts Council Collection. © Maggi Hambling

Since then, Hambling has drawn or painted many of those close to her as they approach death, or in the immediate aftermath: Cedric Morris, her mother, her father, most recently her beloved Tibetan terrier, Lucky. Some of them, as witnessed by two paintings of Lett-Haines in the Marlborough show, continue to appear long after they’re gone. All these portraits are variously a raising of the dead – a version of trying to see the life in the eyes of a stuffed rhino – and a laying to rest; sometimes, perhaps, the two things at once. (A Conversation with Oscar Wilde, in fact, was partly influenced by Etruscan funerary monuments, in which the deceased figures are depicted ‘lolling about on the lids’, as Hambling has so brilliantly put it.) ‘I went on painting George Melly for a couple of years after he died, so there were all these paintings round the walls, and trying to paint them with as much life as possible; and then in the studio, the morning after the lorry had picked them all up to go to the Walker [Art Gallery], I had to say to myself, “Look here Mag he’s dead”, you know, because all the paintings had gone […] As an artist, one is lucky to have that positive way of grieving.’

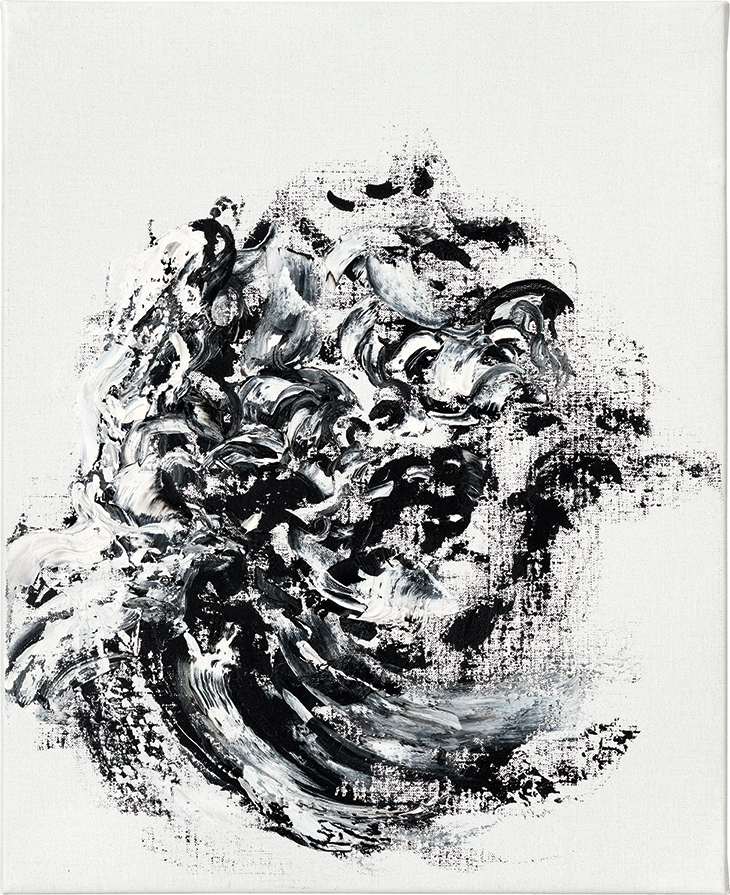

She made several drawings of Henrietta Moraes – ‘queen of Soho’ in the heady Colony Room days and, for the last nine months of her life, Hambling’s lover – in her coffin. The artist has described Moraes, and the effect she had on her life and work, as ‘a force of nature’. And, indeed, Moraes’s death in 1999 prompted a new, elemental subject in Hambling’s work. Although she had grown up near the Suffolk coast, the sea had not featured much in her work before. After Moraes died, however, her sea paintings began ‘in a big way’. Were they part of the grieving process? ‘I don’t know, I mean the big things that happen in one’s life – you only have to go and look at the sea to see how unimportant everything is and how tiny you are.’ There is no doubt in her mind, though, that her early wave paintings are connected to Moraes. She points to a large plaster sculpture on a plinth in one corner of the studio. A swirling white confection, all giant lips, teeth and mouth, the work is titled Henrietta eating a meringue. ‘When she found out she’d got diabetes she tucked into the cream cakes in a big way,’ Hambling says. ‘But that exchange between the meringue and the mouth – particularly round here the sea is like a mouth, devouring the shingle devouring the land. That kind of voracious eating that that sculpture is about, I only saw afterwards, and that kind of movement was what I began to paint with waves about a year later.’

Laughing IX (2018), Maggi Hambling. Courtesy Marlborough Gallery; © Maggi Hambling

The sea, of course, is a rich source for almost any kind of metaphor; but the words ‘ocean waves’ unnumberable laughterings’, from Aeschylus, have resonance for Hambling, and signpost another great theme in her life and work. ‘Laughter is very important to me,’ she says. (She goes on to relate how she refused to add her signature to a letter published in the Evening Standard in 1994 objecting to Brian Sewell’s relentlessly hostile view of contemporary art – including her own – with the explanation: ‘He makes me laugh.’) A final, small room in the Marlborough exhibition is hung with a series of nine paintings, all from 2018, of laughing faces. Again, they look back to previous work from the 1990s on the same subject. Some of them seem to be self-portraits, and Hambling tells me she occasionally studied herself in the mirror (as she did for Young dancing bear) to make them. ‘But it’s very difficult to pose laughing because obviously it’s the thing of a second, the whole point is the chaos of the features; it’s a sort of sexual thing as well, that abandon: if someone really laughs, the guard is gone.’ Some of them, far from being joyful, seem closer to the stares and grimaces of Goya’s Black paintings. ‘I think that’s one of the great moments on a stage,’ Hambling acknowledges, ‘when you don’t know whether to laugh or cry… the two things are so close.’ That knife-edge aspect of humour was partly what led her to ask one of her comedic heroes, the actor and entertainer Max Wall, to sit for her. The resulting painting, Max Wall and his Image (1981), captures the darkness behind a clown’s mask, with Wall’s best-known alter ego, Professor Wallofski – whom he referred to as ‘the monster’ – represented as a sinister silhouette lurking behind him. Hambling went on to paint and draw Wall enough times for a dedicated exhibition that opened at the National Portrait Gallery in 1983.

Max Wall and his Image (1981), Maggi Hambling. Tate collection. © Maggi Hambling

Clown-like figures are occasionally discernible in the ink drawings Hambling makes religiously first thing every morning. These she does with her left hand (she is right-handed), using the dropper straight out of the bottle, often with her eyes closed. The purpose, she explains, is ‘to renew the sense of touch. The thing is, I’ve been at this business since I was 14, so this [right] hand is full of so many tricks. Whatever the left hand comes up with can actually surprise me.’ What she particularly likes about her paintings in the show at Marlborough is their closeness to these drawings (see especially Self portrait 2019) – spare and, though she dislikes the term being applied to her work, more abstract. ‘I’m trying to say more with less, as I get older […] To do something a bit more like Beckett, I suppose.’

Self-portrait (2019), Maggi Hambling. Courtesy Marlborough Gallery; © Maggi Hambling

Canvases of various sizes are ranged round the studio, their faces to the wall like naughty schoolchildren. ‘They’re still cooking!’ she says, but then relents and shows me one of them: a painting of her new rescue pug, Peggy, who has been kept out of mischief during our interview by Hambling’s fellow artist and partner of more than 30 years, Tory Lawrence. ‘You must come and meet Peggy,’ Hambling insists. ‘She’s been a great help through the spills and thrills of Newington Green.’

It would take a good deal, you feel, for anything to truly get the better of Hambling. John Berger wrote of her: ‘If there’s one adjective to describe Maggi, it is courage. She is unflinching. She looks at people, sees their shortcomings and their pain, but she doesn’t look away.’ Reflecting on the way she approaches her work, Hambling echoes these words: ‘Things take their time and decide when to happen. The thing is to be brave, always to be brave…’ Stiffen the sinews. Summon up the blood.

Maggi Hambling, photographed with her pug, Peggy, in November 2020. Photo: Toby Glanville

From the January 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home