Under the museum’s spotlights, the contemporary zip-up jacket designed by Carol Christian Poell looks like a Lee Bontecou sculpture. Shimmering and diaphanous, it is woven from plastic tubing that ripples over the fibreglass torso. The seemingly simple pattern of the piece belies its elaborate construction. All in all, it’s a good example of the expanded definition of ‘fashionable dress’ that the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s exhibition ‘Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715–2015’ attempts to showcase.

Macaroni ensemble: Suit (c. 177), Italy, probably Venice; Waistcoat (c.1770), France; Sword with sheath (late 18th century), France. Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA

Drawing primarily from LACMA’s own splendid collection, ‘Reigning Men’ spans 300 years of what we consider menswear, but the curators have eschewed a chronological narrative in favour of thematic groupings. The display kicks off with the theme ‘Revolution/Evolution’ and an introduction to the macaroni (as in ‘Yankee Doodle’), a type of English dandy from the 1760s and ’70s that favoured vibrant, colour-blocking outfits with tight tailoring. Mocked in contemporary publications, the macaroni set embraced their caricatures, relishing the extravagance. By comparison, the French in the revolutionary period used dress to indicate fervent political affiliations. Accents such as cockades of red, white, and blue ribbons were worn by the supporters of the Revolution, pinned to waistcoats and bicorne hats.

But the term ‘revolutionary’ isn’t limited to any specific historical moment; more recently it has been applied to instances of youthful rebellion. Made-to-measure leather clothing for motorcyclists exploded in popularity after Marlon Brando played a rabble-rousing youth in the 1953 film, The Wild One. In wholesome contrast, model athletes wore letterman jackets, which have their origins at Harvard University in 1865, where students were awarded large letter patches for athletic achievements. They were affixed to uniform sweaters and eventually to jackets from around 1930.

Punk Jacket (1978–83), United States. Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA

The practical aspect of fashion is explored in the section ‘Uniformity’, which features an array of items, from coveralls and examples of business tailoring, to various permutations of denim. A one-piece ‘boiler suit’ produced by Vetra stopped automobile and aviation mechanics from being covered in dirt and soot that emanated from their workspaces. A Phillip Lim version from 2010–11, showcased alongside it, is cut from striped silk, nullifying the practical component of the original. ‘Body Consciousness’, meanwhile, investigates form against function. A pair of corseted underpants from 1830, which nip the waist and flare generously around the hips, exemplifies the shapely silhouette that was so celebrated in the 19th century. A modern example of a golden thong swimsuit, by Tom Ford for Gucci, demonstrates the changing dialogue between fashion and the human figure in the present day.

Clearly, a great amount of attention and care has gone into to this exhibition. LACMA reveals the individual stories behind each item in handsome detail – the catalogue entries are fascinating and painstakingly researched – and it also commendably avoids a form of criticism that compares and contrasts ‘high’ versus ‘low’ culture in the cyclical business of fashion. A rare zoot suit recently acquired by the museum could serve as the nexus for a small exhibition in itself, recounting a fraught midcentury history that marginalised people in the United States experienced and expressed through their choice of dress.

Zoot Suit (1940–42), United States. Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA

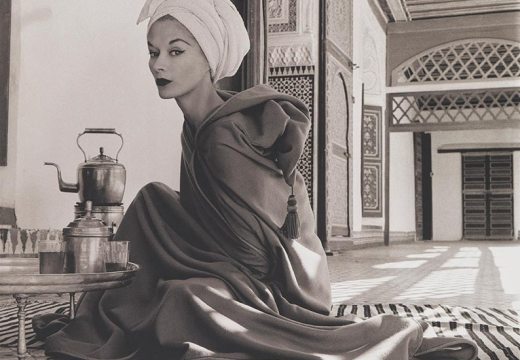

Yet ‘Reigning Men’ skirts around a key topic – the tricky history of Western cultural dominance, and the perpetuation of this narrative in our major cultural institutions. Most of the pieces featured in the exhibition are from Europe, and an awkward but well-meaning thematic binary is established in the ‘East/West’ portion of the show, where cultural intersections are acknowledged but colonisation and colonialism are mentioned only briefly. When the exhibition lands on the 21st-century man, whose mash-up wardrobe encompasses all that is ‘global’ and ‘postmodern’, we are left with only a faint taste of the ideological discourses that accompany such pastiche.

‘Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715–2015’ is at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) until 21 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home