From the June 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Talos, the bronze giant, is said to have guarded Minoan Crete by throwing rocks at unwanted invaders. Michael Ayrton’s bronze statue of this mythological character, Talos (1963), was donated to the City of Cambridge shortly before the opening of the Lion Yard shopping centre in the early 1970s. Positioned on a six-foot-high plinth outside a side entrance, due to its nakedness it initially met with reservation. But neither this nor the figure’s threatening presence has discouraged commerce. Shoppers come and go, amused, perhaps, by the way Talos’s box-like and slightly crinkled chest means that today he faintly resembles a man from Deliveroo.

Talos (Large) (1963), Michael Ayrton. Cambridge City Council. © Estate of Michael Ayrton

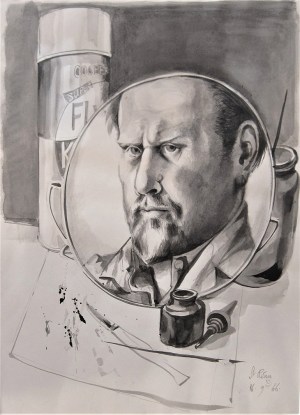

Self-portrait with Mirror (1966), Michael Ayrton. Private collection. © Estate of Michael Ayrton

It is, however, the small version of this sculpture, currently on show in ‘A Singular Exhibition’ (until 31 October) in Saffron Walden, that best conveys Ayrton’s stated intention: ‘A certain tranquillity lies in his stupid presence, a certain comfort,’ he wrote. ‘He has no brains or arms, but looks very powerful.’ Such subtleties of expression recur in this exhibition, one of several events to mark the centenary of Ayrton’s birth this year, and which can be found not in the town’s Fry Art Gallery – currently undergoing alterations – but in the temporary Fry Art Gallery Too, around the corner at 9b Museum Street. At the Lightbox in Woking, another centenary exhibition nicely balances the display in Saffron Walden by giving more weight to the artist’s paintings (until 8 August). Both are welcome: no retrospective exhibition of this major artist has been attempted for 44 years; and, aside from Justine Hopkins’ definitive biography (1994), very little new work on him has been published. Yet in 1955 Bryan Robertson, the influential curator at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, had referred to Ayrton as ‘one of the most gifted artists of his generation’.

Why is Ayrton nowadays largely overlooked, or remembered almost exclusively for his sculptures of minotaurs? Is it because he kept himself apart from artists’ groups after his neo-romantic period? Is it because his sculpture boldly differed from the path that others, such as his friend Henry Moore, had established? Is his reputation damaged by his range and by the British distrust of polymaths? Few painters also, as Ayrton did, design for the theatre, work as an art critic, write books, move into sculpture, broadcast on radio, appear in highbrow TV quiz shows (The Brains Trust), enjoy success in the making of films on artists and find time to become an academic.

But perhaps the resistance to Ayrton is still driven by the fact that he turned his back on Matisse and the Mediterranean and promoted instead the Northern European tradition, preferring its emotionalism and fine detail to the seemingly cold modernity of Cubism? Ayrton had a rare ability to combine the cerebral and the sensuous, as the publisher and critic Tom Rosenthal pointed out. But at a low point in his life the artist admitted: ‘My intellect tears every emotion I have to tatters […] I am left with a sort of sardonic husk.’

Getting to grips with as complex a character as Michael Ayrton is no easy task. But 30 years ago I tried to do so when writing a biography of John Minton. The two men overlapped at St John’s Wood Art School, becoming friends in 1938 during a school visit to Paris. The bonding ingredient was the young Ayrton’s bright love of talk, for although nearly four years younger than Minton, he was much better versed in painters and painting, having visited more galleries abroad. After leaving school at 14, he had gone the following year, 1936, to Paris, where he studied independently – until the Spanish Civil War broke out, that is, and he shot off to Spain filled with pro-Republican sentiment. Learning of this, his mother, Barbara Ayrton-Gould (later chair of the Labour Party and MP for Hendon North) arranged for him to be sent back, after which she posted him to high-standing relations in Vienna. There he happily attended soirées at which Freud was sometimes present. He had also mixed with those members of the London intelligentsia who gathered around his parents (his father, Gerald Gould, writer of fiction and literary critic for the Observer, was regarded as a determining influence on the reading public).

In 1939 Ayrton and Minton shared a studio in Paris. They had recently read James Thrall Soby’s After Picasso (1935), a book which argued that a reaction against formalist art had set in. It sent them in search of the Neo-Romantics – the Paris-based Russians Eugène Berman and Pavel Tchelitchew, as well as the Frenchman Christian Bérard, then more famous as a stage designer than a painter. Ayrton and Minton shadowed these three artists, adopting their exaggerated perspectives and other stagey effects and copying their use of blue, itself inspired by Picasso’s Blue Period. When war broke out, they returned home, bringing a personalised version of this style back to England. As Soby had admitted, French neo-romantic art is occasionally sentimental, ‘but [its] sentimentality is strangely piercing and alive’. So too was Ayrton’s and Minton’s version of Neo-Romanticism.

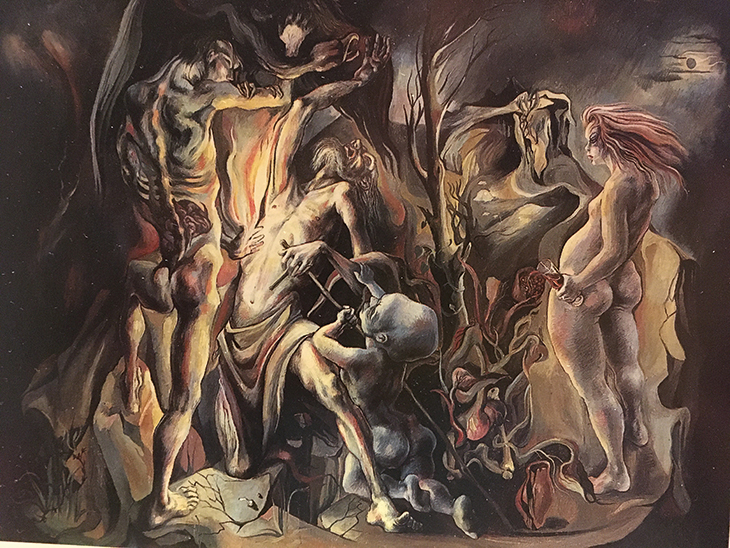

Temptation of St Anthony (1943), Michael Ayrton. Tate Collection. © Estate of Michael Ayrton

In the war years Ayrton began to merge his neo-romantic manner with his admiration for Northern European masters, in particular the work of Bosch, Grünewald and Dürer. This combination can be seen in his series on the Temptation of St Anthony. In the version in the Tate collection, anatomy is twisted or exaggerated to such an extent that the picture seems to shriek with agony. He began work on this subject in 1942 and the following year, in a letter to Ayrton, Minton identified a condition that troubled Ayrton’s art. ‘The realisation of oneself in paint is a long process subject to all sorts of influences and difficulties […] But the fact of what one paints and what one is is inescapably interwoven […] I can only look at your pictures with admiration and wonder – but there is no joy in them for me, no love that I can feel no despair or disquiet or tortured struggle that comes from the red blood of living.’ Minton’s observation of what Ayrton’s art lacked must have stung the latter deeply. When, some years after Minton’s death in 1957, Ayrton was approached for Minton’s letters, this specific letter was produced, in a very worn state, from the inside of his wallet.

For more information about the Michael Ayrton centenary, visit the Ayrton Estate website.

From the June 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home