Franklin, Apple TV’s latest moodily lit historical biopic, begins with our hero, the most versatile American ever to have lived, landing on the coast of Brittany in December 1776. As he steps out of the rowing boat that has brought them ashore, his companion asks, ‘What’s wrong?’ Nothing, Franklin says. He’s ‘merely thinking’. About what? ‘Roast pheasant, potatoes in butter, candied carrots chased by a respectable Madeira. And our mission, of course.’

Michael Douglas plays Benjamin Franklin with gusto. His performance may be quieter than the one he gave as Liberace in the Soderbergh film, but not by much. In the series, and in this period of history, the founding father is on a mission to form an alliance with France for the cause of the American Revolution. A sclerotic monarchical regime can’t be expected to get excited about liberty and equality, but perhaps it can be persuaded to biff its old enemy, Britain, on the nose.

Michael Douglas as Benjamin Franklin. Courtesy Apple TV

To remind us that Franklin is a man of appetites as well as of ideals, another early scene has him fart himself awake at a dinner table. ‘It’s remarkable how one’s outlook is improved by the passing of wind,’ he says. In real life, Franklin’s personal unpretentiousness was a trait he turned to good use while trying to gain the ear of the powerful in France. His plain brown suit, unwigged hair and fur cap all marked him out as a new kind of person, a citizen of a state that did not yet exist.

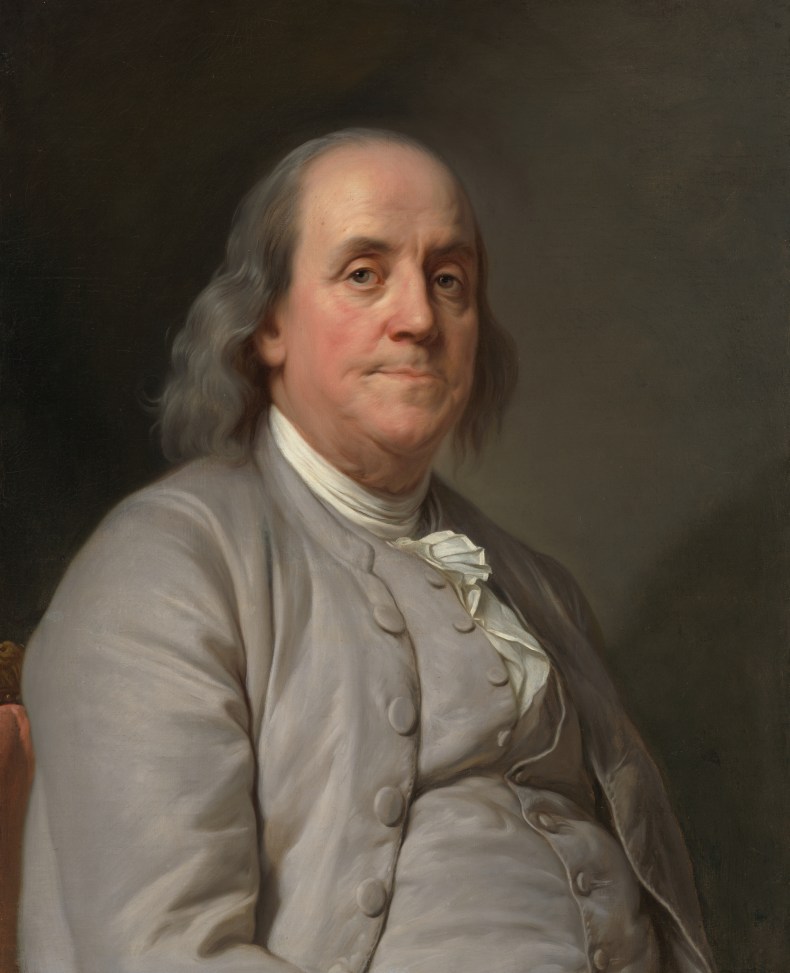

Benjamin Franklin (1778), Joseph-Siffred Duplessis. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

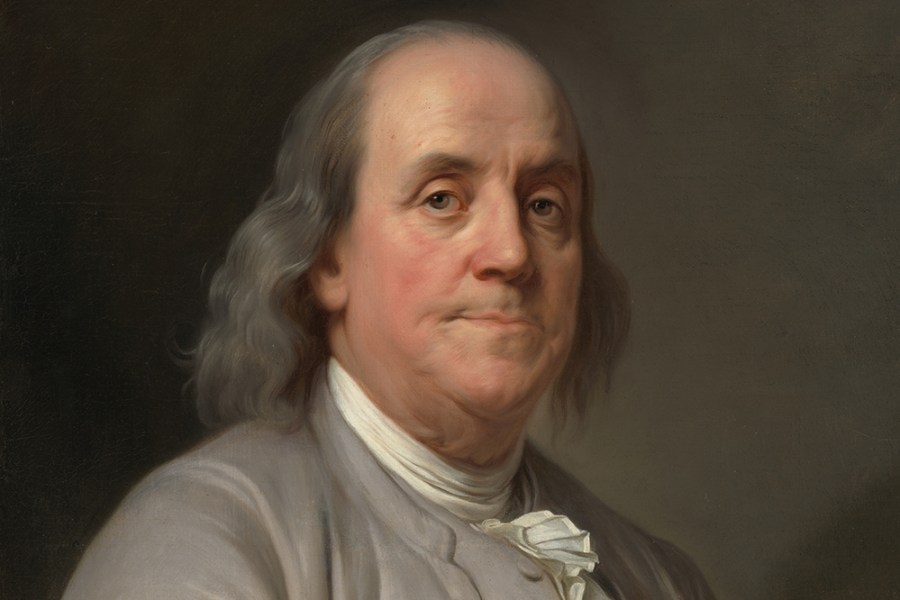

It seems fitting that the painter who did more to fix Franklin’s image in the public imagination than any other was also a flexible figure, who managed to negotiate the upheavals of the French Revolution. Joseph-Siffred Duplessis’s portraits of Louis XVI and Gluck are surprisingly candid depictions of their subjects. The king in his coronation robes looks like a dilettante who has been rootling around a dressing-up box; the composer seems to be hunting a melody down in the act of composition. Duplessis painted Benjamin Franklin more than once. In 1779 his portrait of Franklin was much praised when it exhibited in the Salon that year. But it’s the portrait of c. 1785 that forms the basis for Franklin’s depiction on the hundred-dollar bill. In the former, the statesman wears a reddish-brown suit and a fur collar and his hair loose. In the latter his grey hair is greyer and his outfit even simpler: a grey coat and a white collar. In 1785, Franklin left France having achieved everything he had set out to achieve. The sitter for Duplessis’s second portrait has accomplished his mission and had his fill of roast pheasant and potatoes along the way.

Benjamin Franklin (c. 1785), Joseph-Siffred Duplessis. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home