‘Nowhere can one get to know an artist better than in his prints,’ observed Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. The more than 80 works on display at the British Museum in ‘Edvard Munch: Love and Angst’ – a small but rich sample drawn mostly from the vast archive of the Munch Museum – show that Kirchner was on to something. The lithographs, etchings, and woodcuts distil the artist’s distinctive iconographic style – his tendency toward the unforgettable motif – while evoking the Old Masters he studied. They reveal Munch at his most physical and tactile: carving his pictures into sheets of copper and zinc, inscribing them on limestone, and gouging them into blocks of wood. In this serial medium, Munch tried over and over again to capture the appropriate colour or tone of an image, and struggled to recreate the memory of his young sister on her deathbed, the embodied sensation of lust and terror, or the light of a still summer afternoon.

Munch began making prints in 1894, influenced by the skilled printers in Paris and Berlin, cities he began visiting regularly in the early 1890s. ‘Love and Angst’ is loosely structured around Munch’s move from Kristiana (which reverted to its medieval name, Oslo, in 1905) to these continental capitals and back to Norway again. Each major room features a video slideshow with historical photographs of the cities and dramatic readings, in Nordic-inflected English, of Munch’s letters. These European centres brought a young Munch freshly sprung from the enclave of free-thinking, free-loving bohemians in provincial Kristiana into contact with the artists, writers, patrons, and dealers who would enable the Norwegian to become known by the 1910s as ‘the greatest Germanic artist now living’ and even ‘the Nietzsche of painting’.

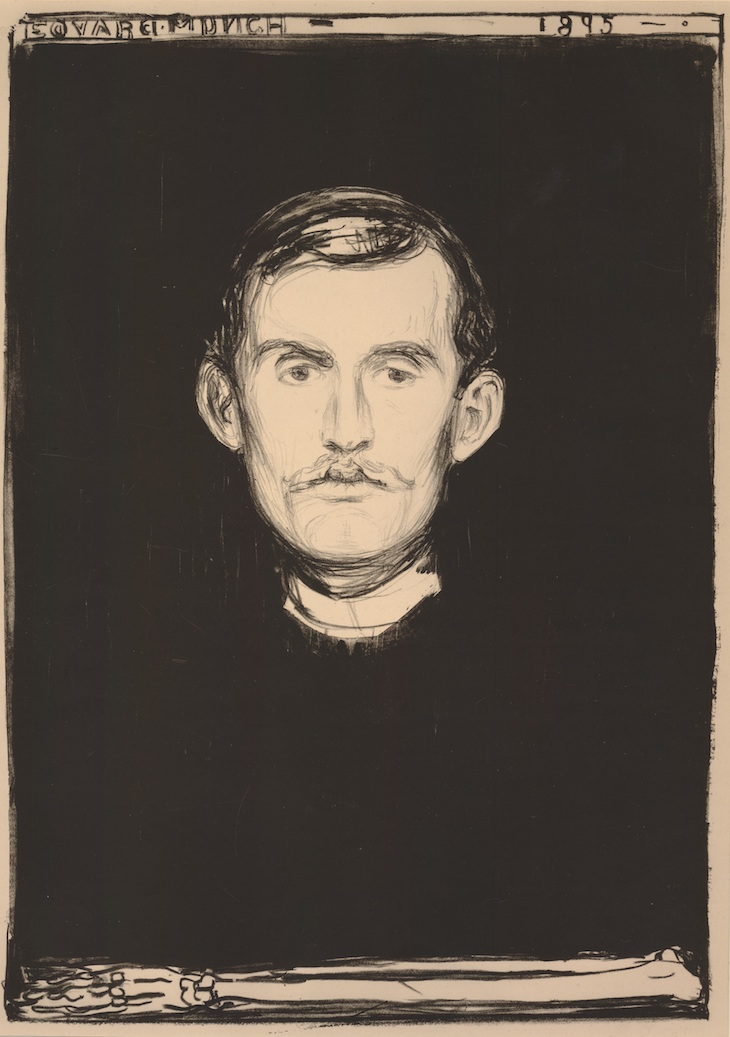

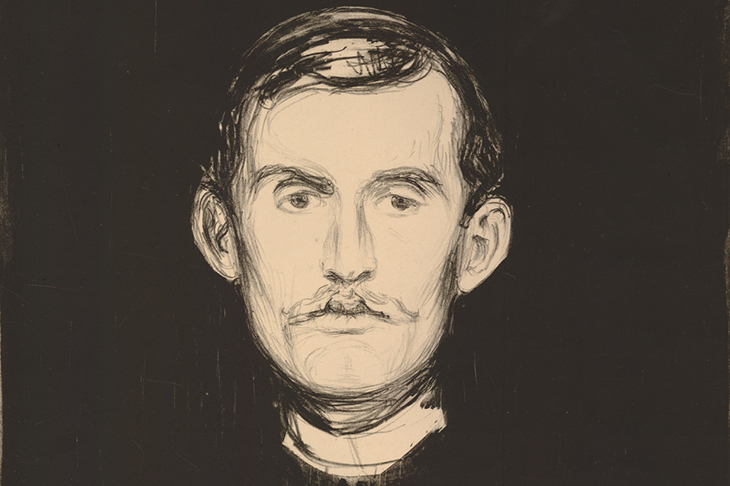

Self Portrait with Skeleton Arm (1895), Edvard Munch. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum

The speed with which Munch took to printmaking astonished his peers. Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm (1895) – the first proper piece in the exhibition – reveals how a talent for drawing meets the distinctive stylistic possibilities afforded by the medium. The ghostly white bone that lies far below the artist’s hovering face is more than just a memento mori: even in this early print, Munch was already inscribing himself in an iconographic tradition that reached back to the Renaissance. The three versions of the hazy café scene Kristiana Bohemians, with their subtlety of tone and texture, show that Munch had learned from Whistler and Degas how to capture the light and depth of interior space in copperplate etching – and, almost as evidence, the copperplate itself is on display, just one small step in the lengthy and labour-intensive process that makes a print.

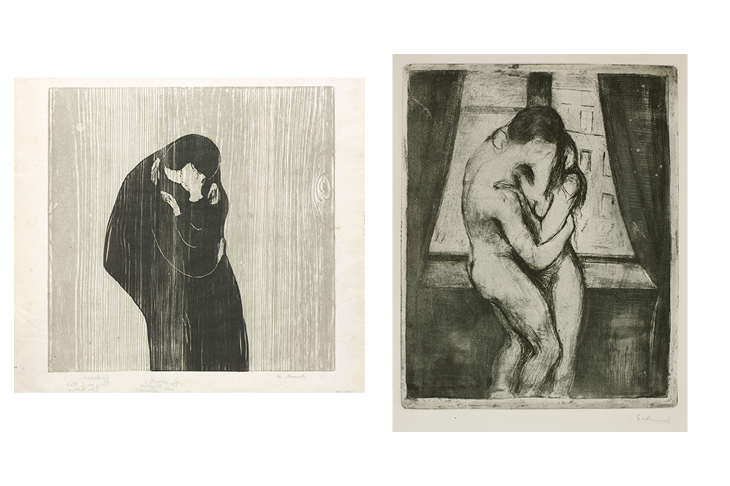

Left: The Kiss IV (lithograph; 1902), Edvard Munch. Photo: Ove Kvavik; courtesy Munchmuseet, Oslo. Right: The Kiss (etching; 1895), Edvard Munch. Photo: Sidsel de Jong; courtesy Munchmuseet, Oslo

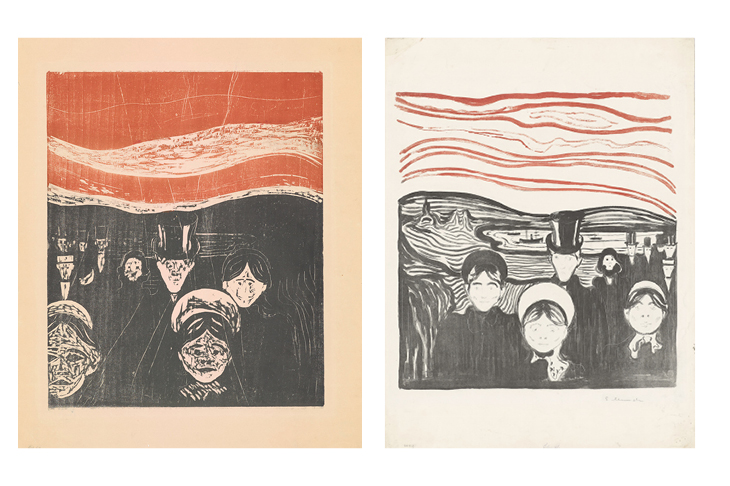

Munch started making woodcuts in 1895 and, at the British Museum, his most original prints are in this medium. The curators juxtapose two images of The Kiss. The first is an atmospheric etching from 1895 that shows lovers embracing in front of a window, curtains drawn as on a stage. Seven years later Munch reinterpreted the motif in woodcut and, although one can see a family resemblance, the later version comes from a different artistic universe. The Rodin-like bodies of the lovers become a Banksy silhouette, their bodies almost undifferentiated in the same black mass except for the three thin lines that delineate their arms, and the white splotches of their hands and face. The grey background is textured with the wide grain of the woodblock, and runs through the shadow of the lovers like rain. In another room, two versions of Angst (1896) hang side by side: a lithograph in black and red, showing a crowd of ghost-like faces standing by a harbour beneath a bloody sky. The wavy lines with which Munch textures the landscape and the clouds seem to be striving toward the energy inherent in the grain of a woodblock, and toward the style of a woodcut. The woodcut version of the image looks like something from another era, the spectral white faces transformed into archaic masks, the sinuous lines of the red sky thickened into the striations of sedimentary rock.

Left: Angst (woodcut; 1896), Edvard Munch. Right: Angst (lithograph; 1896), Edvard Munch. Photos: Halvor Bjørngård; courtesy Munchmuseet, Oslo

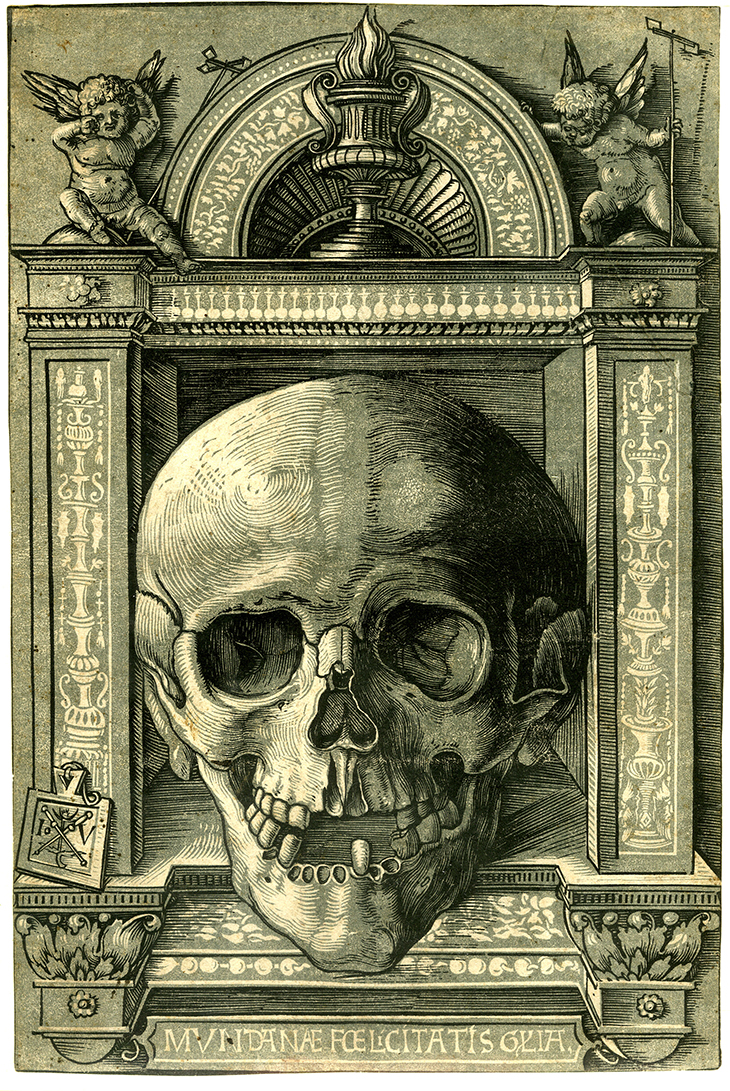

An attempt is made to place Munch within the intellectual-historical currents of the day, with some feeble references in the wall texts to Nietzsche, the death of God, and the scourge of tuberculosis. More interesting, and unexpected, is the room devoted to Munch’s work in the theatre, as the illustrator of several programmes and sets for productions in Paris of plays by Ibsen, whose complicated relationship to Norway resembled his own. But the most revelatory aspect of the show is the inclusion of a small display of Old Master woodcuts: Lovers Surprised by Death (1510), made by Hans Burgkmair, Hans Wechtlin’s Skull in an Ornamental Frame (c. 1510), and Hans Holbein’s renderings of Death and the Ploughman and Death and the Child, from a copy of the Imagines Mortis (1545). Munch’s Symbolism, we discover, draws on the essentially Christian style of early modern visual allegory for existentialist, rather than religious, ends. A whole show could and should be devoted to Munch’s relationship to the Old Masters.

A skull set into an architectural frame (c. 1510/13), Hans Wechtlin. Photo: © the Trustees of the British Museum

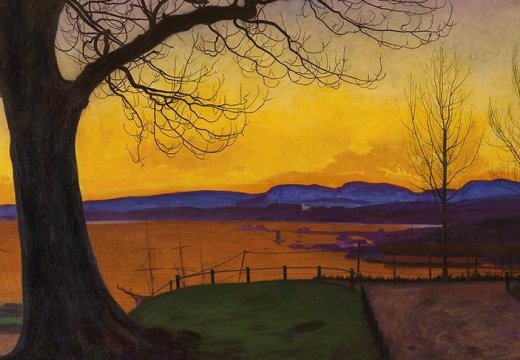

The final room of ‘Love and Angst’ is called ‘Homecoming’ and presents some of the prints Munch made when he returned to Norway after more than two decades without a firm foundation. In this final movement of his life, after unimaginable success as well as debilitating mental illness, passionate love affairs but no marriage, the artist spoke of his images as his children. Prints became a means of keeping his artistic offspring close by even as his creations spread across the world. The show ends with two prints made during the artist’s first years at Ekely, the country compound he bought in 1916 and where he would remain until his death in 1944. In two impressions of The Girls on the Bridge (1918), one slightly more colourful than the other, three young women face away from us, looking out on the placid water. The peaceful scene in blues and greens rewrites the black and crimson seaside traumas of Angst and The Scream. These prints feel very far away from the dramatic Self Portrait with Skeleton Arm with which we began. But in their own quiet way, they are no less serious, and no less powerful.

‘Edvard Munch: Love and Angst’ is at the British Museum until 21 July.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home