A round-up of this week’s reviews and interviews

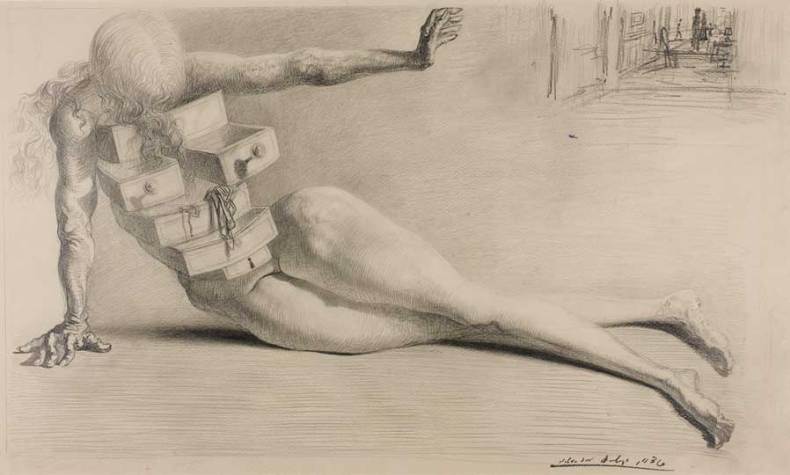

Discovery of desire: Sade at the Musée d’Orsay (Matthew McLean)

[T]he exhibition ends up on the one hand examining Sade as a concrete inspiration for certain artists (e.g. Masson), and on the other treating him as a kind of synecdoche of a much broader cultural tendency, encompassing artists with no demonstrable direct links to his thought (e.g. Greuze). The question thus arises of exactly what work belongs to this broader Sade-ian canon, and what doesn’t. If it makes sense for Hans Bellmer to be well represented in this display, showing us as he does the body as an erotic vehicle, deformed by desire – why not also, say, Renoir, who, for all his surface prettiness, practises his own erotic distortions?

Jenny Saville rethinks the ‘Rubenesque’ at the Royal Academy (Emily Spicer)

It is a strange, jarring experience to enter Saville’s room – to move from the dimpled pastel flesh of a sleeping nymph to a tiny blue cubist portrait by Picasso…without the baroque veneer, without the pearls and putti, we are left with the raw essentials of the themes represented in the adjacent exhibition.

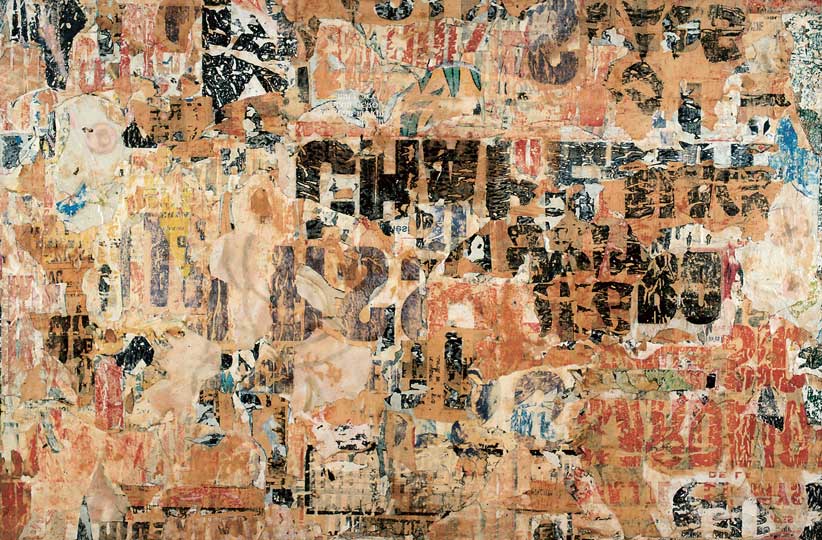

First Look: ‘Poetry of the Metropolis’ at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (Esther Schlicht)

Our general idea of the early post-war period in Paris is still very much informed by the strong influence of Jean-Paul Sartre and Existentialism. In fact, the artistic scene was extremely rich and heterogeneous, and it is intriguing to see with how much humour and nonchalance the French Affichistes François Dufrêne, Raymond Hains, and Jacques Villeglé used from square one.

Cleaning the Core, Ponte City, Johannesburg (2008), Mikhael Subotzky & Patrick Waterhouse. Courtesy Goodman Gallery © Magnum Photos

Snapshots of Ponte City’s residents fill one gallery wall, in a gridded display that echoes the windows of a tower block with half the lights off. Opposite is a row of large-scale photographs of interior scenes; the people captured are life-size and their poses uncomfortably natural: a woman stoops with a dust-pan and brush in her kitchen of yellow 1970s tiles; some teenagers play on their phone beside a window and a basket of laundry. They are familiar to the point that it feels intrusive to observe them.

Community conscious? ‘Cotton to Gold’ explores industry and philanthropy (Wessie du Toit)

Community conscious? ‘Cotton to Gold’ explores industry and philanthropy (Wessie du Toit)

This collection-of-collections, occupying the charming faux-gothic Two Temple Place, is eclectic enough for the internet age…Yet from all this arises some quite cohesive insights into late industrial society. For one thing, you get a clear picture of the obsessive curiosity – the need to gather, categorise, understand – which animated Britain’s middle and upper classes during the age of Empire. You get a feel for tastes of the period. But most striking to me is the notion of community presented here, bound by ethics and articulated through culture.

First Look: ‘Shatter Rupture Break’ at the Art Institute of Chicago (Sarah Kelly Oehler and Elizabeth Siegel)

First Look: ‘Shatter Rupture Break’ at the Art Institute of Chicago (Sarah Kelly Oehler and Elizabeth Siegel)

The first half of the 20th century was a period of tremendous change – two world wars, new technologies that accelerated the pace of life, new understandings of psychology and the mind, and the disruption of old artistic traditions – and artists responded with both exhilaration and anxiety. We wanted to explore how the idea of rupture permeated modern life…The process alone has been stimulating, and it has been a wonderful reminder of why we chose to be curators.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home