A round-up of the week’s reviews and interviews

Apoxyomenos (detail of head; Hellenistic or Roman replica after a bronze original from the second quarter or the end of the 4th century BC) © Tourism Board of Mali Losinj

The difficulty of ‘Defining Beauty’ (Ruth Allen)

Some bodies at first glance appear straightforward: the first room presents four icons of classical sculpture, epitomes of the Greek male body-ideal and the Greek commitment to ever-more naturalistic depiction. But their ‘realism’ is deceptive. A bronze athlete seen scraping his toned body clean of oil and dust presents an impossible, hyper-realistic version of male beauty…Likewise, Myron’s Diskobolos depicts not a real athlete but a synthesis of parts combined to create a quasi-abstract ideal; and Polykleitos’ Doryphoros is a mathematically perfect body, balanced, ordered, symmetrical. These aren’t real men: they are supermen.

Roman Riot Club: ‘The Baroque Underworld’ draws crowds at the Petit Palais (Caroline Rossiter)

Vice has always been a draw. Artists visiting Baroque Rome enjoyed drinking and brawling as much as the splendours of the Eternal City. Today visitors are lured to the Petit Palais’ new exhibition, ‘The Baroque Underworld: Vice and Destitution in Rome’, by the promise of a taste of this gritty milieu. The success of the exhibition has even provoked security concerns for the works on display. Le Figaro reported on 10 March that there were over 21,000 visitors in the first two weeks of the show’s opening.

One of the largest race riots occurred in East St. Louis. Panel 52 from ‘The Migration Series’ (1940–41), Jacob Lawrence © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Powerful, humbling and relevant: Jacob Lawrence’s ‘Migration Series’ at MoMA (Louise Nicholson)

Lawrence depicts the insults, injustices, hardships and hope. He shows with indisputable directness what people left behind – the flooded crops, the lynchings. He shows how they travelled north – the crowded trains, the thousands of miles walked by many families. And he shows what they found when they got there – yes, more food, better education and housing, employment in the steel industry, the freedom to vote, but also prejudice and race riots, a different kind of discrimination. It is this discrimination that will resonate with every person looking at these images today, in light of recent events across the US.

London Diary: Digby Warde-Aldam surveys the city’s art scene

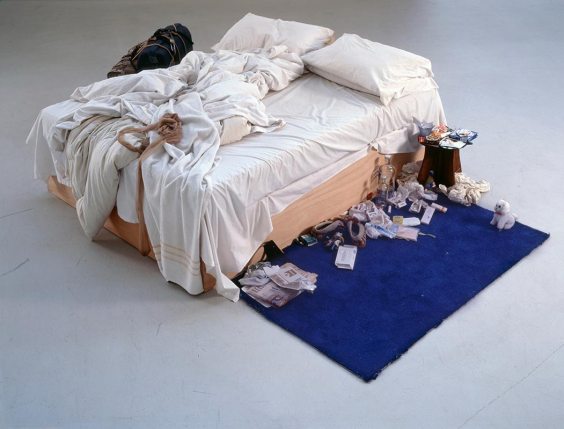

When I first saw Tracey’s bed, at the 1999 Turner Prize show, I was 10 years old and so clueless I would’ve believed Picasso was a realist if you’d told me. I had no conception that art was about anything but pretty pictures of trees and buses. Seeing My Bed, it was as if the floor had disappeared beneath my feet. Naff though it sounds, Emin’s work changed the way I thought about almost everything.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home