A round-up of the week’s reviews and interviews

Exhibition View, ‘Raoul De Keyser: Paintings 1967 to 2012’, at Inverleith House, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Courtesy of private collection, Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp, and David Zwirner, New York/London.

Raoul De Keyser at Inverleith House (George Vasey)

In the later paintings ambiguous shapes often float in space, suggesting clouds or islands. De Keyser’s great talent is to keep oppositional ideas in the balance: forms can simultaneously suggest geological or domestic motifs. De Keyser is fond of these productive misunderstandings. The paint is often applied as thin as cream and sometimes as thick as butter, yet always chalky and matte and retaining the quality of a sketch. The surface is worked on and through, revisited and revised.

‘A K Dolven, please return’ (installation view, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, 4 February–19 April 2015) ikon-gallery.org. Photo by Stuart Whipps

A K Dolven explores Norwegian landscapes in Birmingham (Anneka French)

A K Dolven’s work is supremely elegant. Exploring her body’s sensual relationship to the Norwegian landscape that she calls home (when she’s not living in London, that is), the paintings, video and sound works currently on show at Ikon gallery in Birmingham are beautifully simple. Some of them seem barely there, yet there is a wry humour to be found in each one.

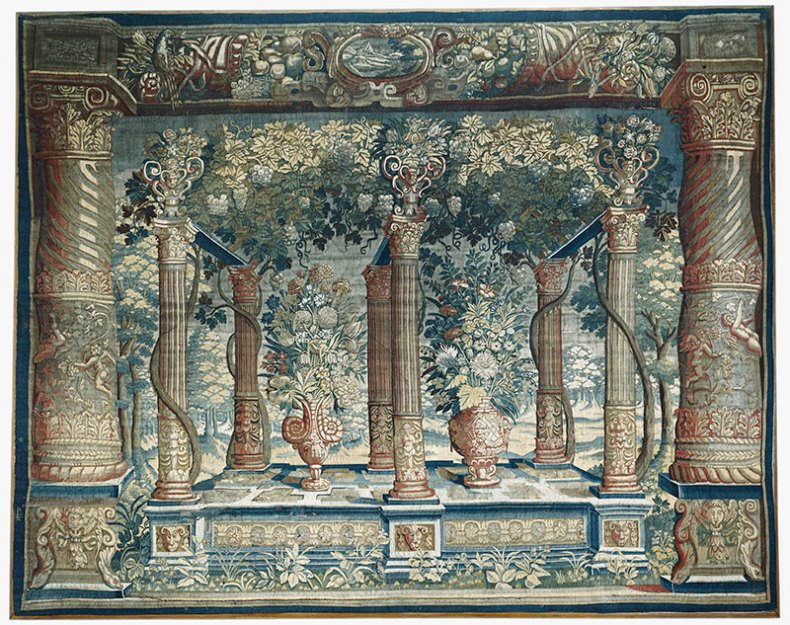

First Look: ‘Painting Paradise’ at The Queen’s Gallery (Vanessa Remington)

‘Painting Paradise’ will explore the ways in which the garden has been celebrated in art through a display of over 150 paintings, drawings, books, manuscripts and decorative arts from the Royal Collection. Through spectacular paintings of royal landscapes, jewel-like manuscripts and delicate botanical studies, it will reveal the changing character of the garden and its enduring appeal for artists.

Richard Long: The Last Amateur (Jon Day) From the March issue

‘Leaving a mark. That’s central to my work’, [Long] says. ‘It’s just a human mark. With my body, or with my gestures.’

As well as getting him out of the gallery, one of the attractions of the walking sculptures was that they liberated him from the need to produce objects, leading to a minimalist simplicity that he sees as a product of his time. ‘I think that was a characteristic of that generation,’ he says. ‘Conceptual art did come about, partly, through asking: why fill the world with more junk?’

The Corning Museum of Glass’s new Contemporary Art + Design Wing, designed by Thomas Phifer and Partners. Photo by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the Corning Museum of Glass

The Corning Museum of Glass unveils new contemporary galleries (Tina Oldknow)

Acquisitions happen in so many ways, and each artwork has its own story. Like most curators, I keep a wish list of the objects I believe the institution needs. I am always thinking about potential acquisitions, and I usually (but not always) watch an artist’s career develop for three or four years before bringing their work into the museum’s collection. The museum often buys works from galleries or, more rarely, at auction. Sometimes something pops up that wasn’t on the wish list, but is interesting for the museum to have. Acquisitions can take a couple of years, or they can take a couple of months.

‘Classicicity’ installation view at Breese Little, London (5 March–2 April 2015) Photo: Tom Horak. Courtesy Breese Little, London

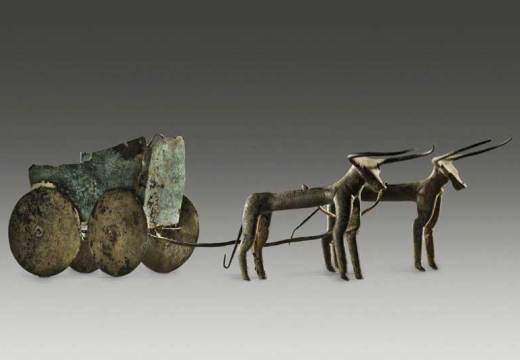

Work in Focus: Surreal subjects at ‘Classicicity’ (Ruth Allen and James Cahill)

One of the most striking ancient objects in the show is a Roman marble relief panel depicting a scene from the Mithraic Mysteries, a cult dedicated to the worship of the god Mithras. Mithras is thought to have been an Eastern deity who became increasingly popular at Rome from the 1st to 4th centuries AD, although his origins are unknown. The exact nature of his worship is as obscure, shrouded in secrecy even in antiquity.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home