A round-up of the week’s reviews

Out of time: ‘Digital Revolution’ at the Barbican (Jack Orlik)

Achronism isn’t just something we witness in old sci-fi films, but a feeling that bubbles up in ourselves from time to time. It is that sense that we were looking the wrong way during the latest developments in technology and culture, and have somehow been existing in an alternate present that runs parallel to the world in which everybody else has been living. It can be pretty disorienting.

Back in the Barbican, one of two things has happened. Either the building’s own achronism has magically cancelled out that of the digital devices and artworks that it is currently showing, or ‘Digital Revolution’ is an extremely well put together exhibition.

Curcuma sul travertine (1991), Shelagh Wakely. Loose turmeric powder. Courtesy Camden Arts Centre. Photo © Heini Scnheebli

More than ‘women artists’: Dorothea Tanning and Shelagh Wakely in London (Belinda Seppings)

Dorothea Tanning famously said that the term ‘woman artist’ was ‘disgusting’. Perhaps she would have been frustrated by recent coverage of art world gender imbalance – which often discusses the issue in those terms – as Web of Dreams, a selection of her paintings and works on paper, opened at Alison Jacques Gallery.

Despite Tanning’s revulsion of female categorisation, it is difficult to approach this show without placing significance on the artist’s gender: her work focuses heavily on the female form.

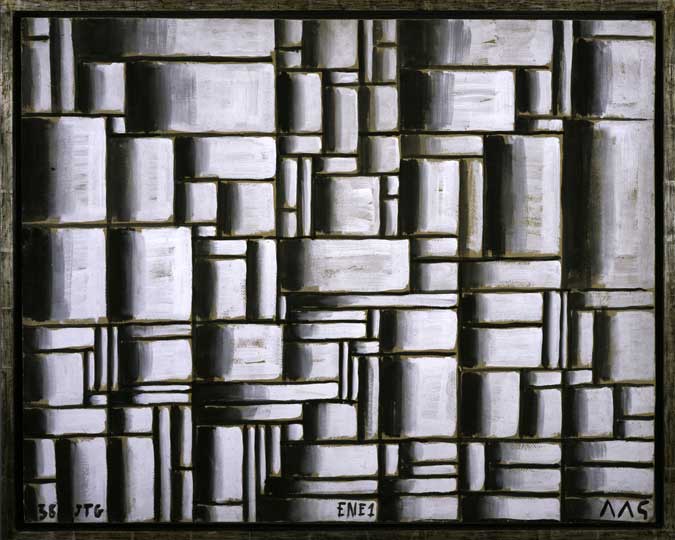

Construction in White and Black (1938), Joaquin Torres-Garcia. Photo Coleccion Patricia Phelps de Cisneros

‘Radical Geometry’, South American art at the Royal Academy, London (Catherine Spencer)

The sense of experimentation prompted by artistic encounters courses through the show. It can be found in the cheeky blue square that appears in the Venezuelan artist Jesús Rafael Soto’s Homage to Yves Klein (1960), suspended in a web of frenetic wires. It infuses the intricate hanging sculptures made from interconnecting metal threads by the artist Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt), a German refugee who travelled to Venezuela in 1939.

Manifesta 10 in St Petersburg (Emma Crichton-Miller)

Russia has always played a tangential role in Manifesta – after all, the biennial was inspired by the breaking up of the USSR and in opposition to the cultural repression that the Soviet Union had represented…[T]o move into the jaws of the great bear itself has seemed to many a step too far…

With global politics so dominant in the conversation surrounding Manifesta, there was a danger the art might become an irrelevant sideshow. In the event, König and Piotrovsky have steered a careful course.

Virginia Woolf (detail; c. 1912), Vanessa Bell © Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett. Photo © National Trust / Charles Thomas

Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision’ at the National Portrait Gallery (Jon Day)

The Grafton, thank God, is over’ wrote Virginia Woolf after Roger Fry’s second exhibition of post-Impressionist paintings at the Grafton Galleries in 1912, ‘artists are an abominable race. The furious excitement of these people all winter over their pieces of canvas, coloured green and blue, is odious.’ Woolf always had, or pretended to have, a conflicted relationship with the visual arts. Though she admired the work of and ideas of Fry and Clive Bell, it was an admiration often tempered by impatience.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Is the Stirling Prize suffering from a case of tunnel vision?