A round-up of the week’s reviews

Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Ground (c. 1823), John Constable © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

‘Constable: The Making of a Master’ at the V&A (Martin Oldham)

Constable projects an idea of himself through these paintings as someone who has an immediate and personal experience of the landscape, operating outside of academic convention. Plein-air sketching, expressed through loose brushwork and a free handling of the paint became the signatures of his authenticity…This conception of Constable has proved to be remarkably persuasive and enduring, but it is what the V&A exhibition now aims to overturn.

‘British Art at War: David Bomberg’ on BBC Four (Camilla Apcar)

This series is a perfect example of how ploys to find ‘timely’ links to anniversaries and milestones – in this case the First World War centenary – can fall flat. Paul Nash is the only member of the trio that may be described as a ‘war artist’. Sickert and Bomberg are more often shown more at war with themselves and the art world, while the actual fighting went on elsewhere.

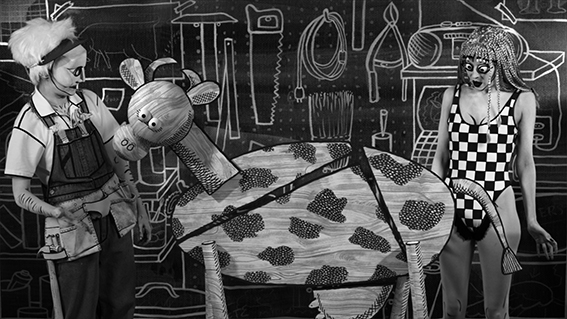

Swinburne’s Pasiphae (2014, HD video still), Mary Reid Kelley with Patrick Kelley © the artist. Courtesy Pilar Corrias, London

Modern Myth: Mary Reid Kelley’s ‘Swinburne’s Pasiphae’ (Tim Smith-Laing)

In its simplest sense Swinburne’s Pasiphae is just a one-woman film production of a 19th-century melodramatic fragment, accompanied by a selection of props and small paintings. It wouldn’t be ungenerous to Swinburne to say that text itself is hard to take seriously on the page: a soggy morass of overwrought, alliterative verse that exemplifies the worst excesses of Victorian sensational style. Mary Reid Kelley’s own style, however, manages to transform the melodrama, despite reading it straight.

‘Ordinary Beauty: The Photography of Edwin Smith’ at RIBA (Owen Hopkins)

When I visited ‘Ordinary Beauty’ on the afternoon of its first Saturday, there was a trickle of visitors. This was fortunate as the small galleries have been packed with more than 100 photographs, giving a full sweep of Smith’s oeuvre. Partly biographical, partly thematic, the exhibition begins with Smith’s first forays into photography before the Second World War. Several quotations are emblazoned on the walls at various stages of the exhibition, though the first, from Smith himself, is the most significant and also the most poetic: ‘I am an architect by training, a painter by inclination, and a photographer by necessity’.

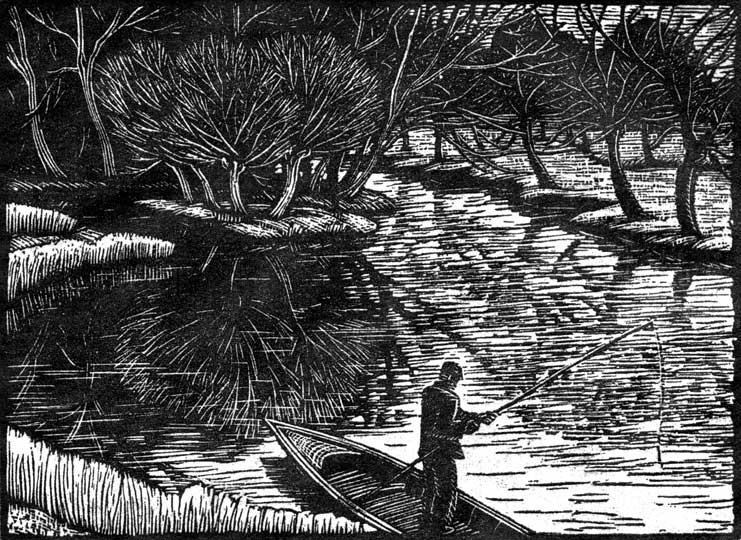

Small town life: Gwen Raverat at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge (Thomas Gayford)

Displayed in Helen Ede’s minimalist former bedroom, the woodcuts are mainly devoted to pastoral scenes of life in Cambridge during the 1920s and ’30s. They all communicate a tremendous feeling of peace, evoking the languorous rhythms of small town life, and Raverat’s distinctive use of dark shading produces an unhurried, muted effect. Apart from a group of men enjoying a game of bowls, the subjects of the prints are mostly landscapes, populated by nothing more active than a herd of cows, or a drift of swans, whose rippling progress under a bridge seems almost frantic in comparison to the other prints.

The sound of war: Susan Philipsz’ Broken Ensemble at Eastside Projects (Anneka French)

The musical instruments in her ensemble have all been damaged by war, a fact which charges the exhibition with a sense of sadness and loss. It hardly needs to be said that conflict is a charged theme this year. The First World War Centenary has been the focus of many recent museum exhibitions, but the trumpets, bass ophicleide, bugle and horn selected by Philipsz were used in earlier conflicts, in Germany during the second half of the 19th century.

Cloisonné enamel jar and cover with dragons (1426–1435), Beijing © The Trustees of the British Museum

‘Ming: 50 years that changed China’ at the British Museum (Alice Williamson)

Reading the title of this exhibition you could be forgiven for thinking that the Ming dynasty lasted for 50 years. In fact it lasted for 276 (1368–1644) and the exhibition focuses on 1400–1450, a period in which Beijing was established as the capital and China experienced a ‘golden age’ of prosperity and artistic creation. The first thing that comes to mind at the mention of ‘Ming’ is blue and white porcelain; but the artistic creations of this flourishing early period were far more diverse.

Modern ruins steal the show in ‘Constructing Worlds’ (Richard Martin)

The show begins its chronicle of the modern age in a conventional time and place – New York in the 1930s, all dazzling angles and sharp contrasts in Berenice Abbott’s black and white photographs…In the second half…the images get more global, more contemporary and much bigger…[F]or many photographers it’s been modernity’s ruined spaces and architectural failings that have proved most compelling.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home