A round-up of the week’s reviews…

‘Departure’ (1932–35), Max Beckmann. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/ Art Resource, NY © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

This is an exhibition about an exhibition: the famously – and conspicuously – ‘badly curated’ exhibition of Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst), opened in Munich, in 1937, by Adolf Ziegler, the National Socialist president of the Reich Chamber for the Visual Arts.

It was organised in parallel with the ‘Great German Art Exhibition’, also in Munich, where the art on show – sanctioned and selected by the National Socialists – was displayed coherently on otherwise clean walls. The so-called degenerates were, by contrast, hung crassly, jostling wonkily for space on crowded walls, misattributed and incorrectly labeled.

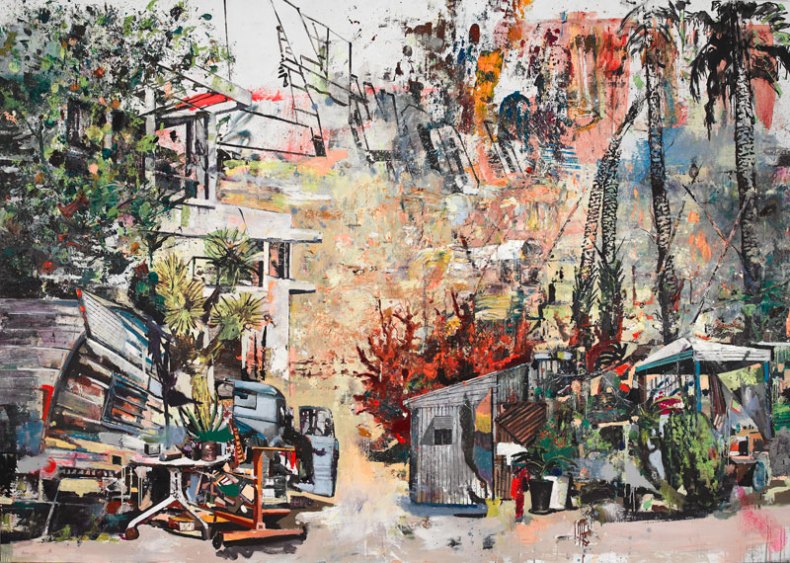

Seasonal Capital of Itinerant Crowds (2013), Marius Bercea © Marius Bercea. Courtesy Marius Bercea and Blain|Southern

Marius Bercea at Blain|Southern (Lowenna Waters)

This exhibition of works by the Romanian artist Marius Bercea (b. 1979), all dating from 2013, brings an explosion of neon brights to Blain|Southern’s galleries on Hanover Square. The result of a road trip from his Transylvanian hometown Cluj-Napoca to Los Angeles, his dreamscape canvases meld the flotsam of Americana with traditional Romanian cultural motifs, the rural with the urban, and thick daubs of impasto oil with light washes of neon.

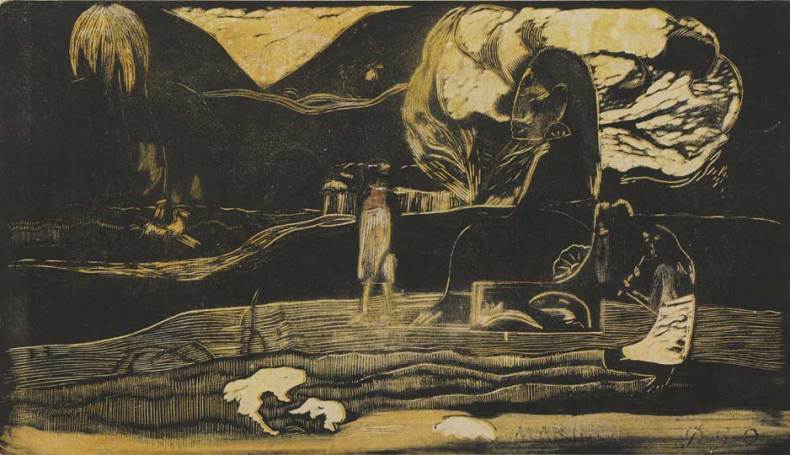

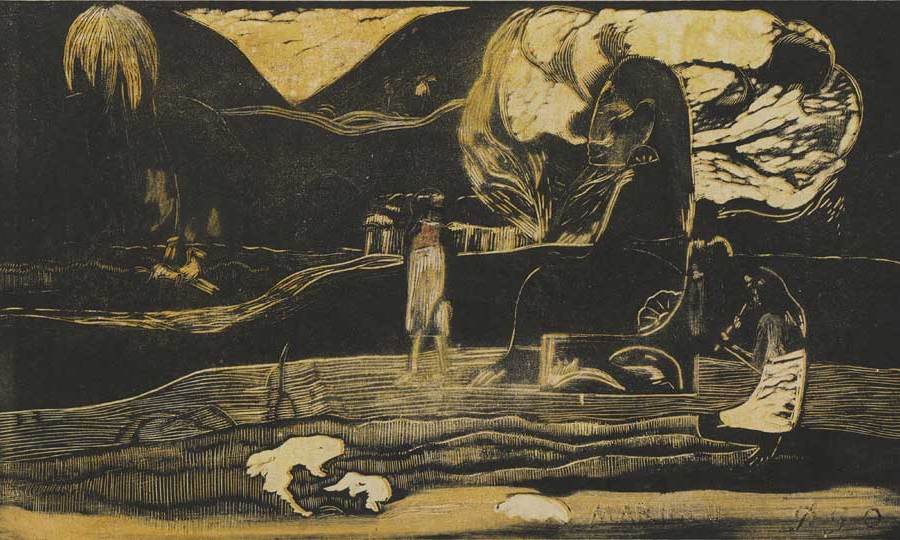

Maruru (Offerings of Gratitude), from the suite Noa Noa (Fragrant Scent, 1893–4), Paul Gauguin. Photo by Michael Agee © Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts

Curator’s Notes: ‘Gauguin: Metamorphoses’ at MoMA (Starr Figura)

We wanted to highlight the extraordinarily inventive nature of these works and show how groundbreaking they were. The more we studied them the more we realised that they also offered a fascinating window into Gauguin’s creative process.

‘The Craze for Pastel’ at Tate Britain (Jon Sanders)

‘The Craze for Pastel’ at Tate Britain, contends that from the 1710s pastels moved to the foreground of English art. A small display of some of the gallery’s rarely seen drawings and paintings, it attempts to review the breadth and flexibility of pastel works and reveal chalk as an indispensable tool for the period’s great artists.

Gerry Judah’s First World War memorial for St Paul’s Cathedral (Peter Crack)

The overall effect is plaintive and abrupt. These jagged and conspicuous structures, ironically rendered in a brilliant white, effectively call to mind the violence of war.

Judah’s work is also suitably iconoclastic, both recalling the mass graves of Flanders and subverting the symmetry of Christopher Wren’s majestic Nave walls.

‘Artist Textiles: Picasso to Warhol’ at the Fashion and Textile Museum (Carey Gibbons)

Raoul Dufy’s charming, whimsical patterns from the 1920s open the show, incorporating everyday objects and activities (Les Violins; Le Tennis). Dufy’s quirky designs paved the way for the Surrealists Salvador Dalí and Marcel Vertès, who collaborated with the American designer and entrepreneur Wesley Simpson in the 1940s. Dalí’s Desert Rocks (1947) and Vertès’ Radishes (c. 1945) are unexpected interpretations of common objects, perhaps reflecting a need after the Second World War for a new way of life and a perspective that could embrace both the accessible and the unfamiliar.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home