I was not an art-museum kid. When I was growing up in Boston my parents – a doctor and a computer engineer – did take me to the Museum of Science often enough. But it was not until I was in high school that I remember making it to the Museum of Fine Arts. The occasion was a high school field-trip to see the exhibition ‘Monet in the ’90s: The Series Paintings’. It was 1990, and I was 17 years old. Today, as a professional curator myself, I might see such an exhibition through slightly jaded eyes: Impressionism is so very bankable at the box office. And, indeed, that exhibition did break records at the MFA, drawing more than half a million people. But at the time I didn’t know any of that. As I looked at wall after wall of haystacks and cathedral frontages, all I could see was a magical combination of the lush and the rigorous, the sensual and the systematic.

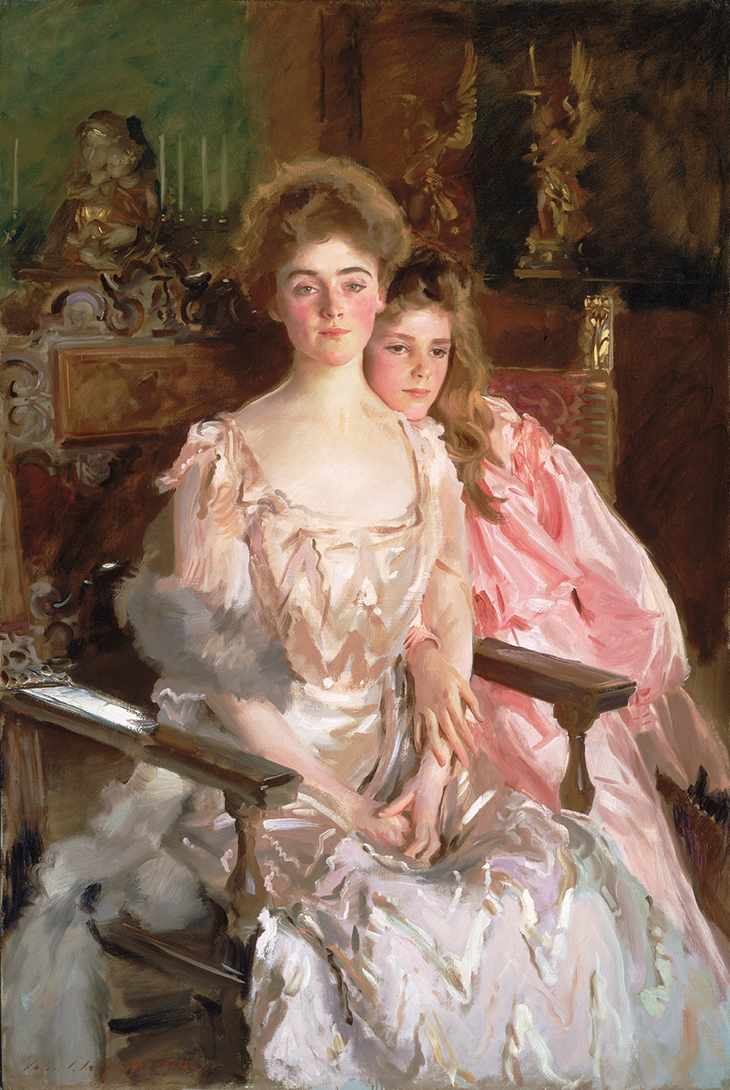

Over the next few years, as I was training to become an art historian, the MFA served as my walk-in bible. I discovered my favourite patch of paint anywhere, in a picture by John Singer Sargent: a startling knife-scrape of white, floating on a pool of viridian green, which blasts through the decorum of a society portrait while still conveying the idea of reflected light on polished wood. After falling hard for Asian ceramics in an undergraduate seminar, I spent long hours poring over the MFA’s holdings of Chinese and Korean celadons, appreciating the magical simplicity of these jade-coloured wares.

Mrs Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and her Daughter Rachel (1903), John Singer Sargent. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

As I gradually began to learn about modern craft, which has remained my core field of study, I came to appreciate the simple genius of the museum’s pioneering programme ‘Please Be Seated’, the brainchild of curator Jonathan Fairbanks. This initiative involved commissioning handmade furniture for the visiting public’s use, offering them the chance to try out a Sam Maloof chair or a Wendell Castle settee. Fairbanks had to overcome objections from his colleagues that this would encourage visitors to touch all the other art. In practice, it was much the reverse: once people had a chance to satisfy their tactile sensation, they left the sculpture and paintings alone.

When I got to graduate school, at Yale, my relationship with the MFA acquired further levels of intimacy. I was lucky enough to study with Edward S. Cooke, Jr., who had just completed a stint in the museum’s American decorative arts department. Through him I got to meet Fairbanks, as well as other curators there like the British silver expert Ellenor Alcorn (now at the Art Institute of Chicago). These days I have many close colleagues who work at the MFA. Most of them entered the field about the same time I did. No longer does the museum seem to me like an awe-inspiring edifice; visiting feels more like dropping by a friend’s house, to see how they’re getting along.

And it does seem a good time to stop in, as the MFA is (like the Metropolitan Museum of Art) celebrating its 150th anniversary this year. Like most of the big American museums, its key strengths were established early on. The holdings of Egyptian and Nubian antiquities (the latter presented in a recent exhibition, ‘Ancient Nubia Now’) were formed largely in the early 20th century, through a series of expeditions undertaken in partnership with Harvard University and led by the archaeologist George Reisner. Around the same time, a coterie of connoisseurs assembled the MFA’s world-class collection of Japanese art. Few worried then about conflict of interest, and the museum’s biggest benefactors in this area, the collectors Edward Sylvester Morse and William Sturgis Bigelow, were themselves staff curators. The museum also worked extensively with two of the most colourful characters in Japanese art at the time: the educator Ernest Fenollosa, who conducted the first formal inventory of Japan’s national treasures; and the aesthete Okakura Kakuzo, who is still remembered for his atmospheric Book of Tea (1906).

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–98), Paul Gauguin. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

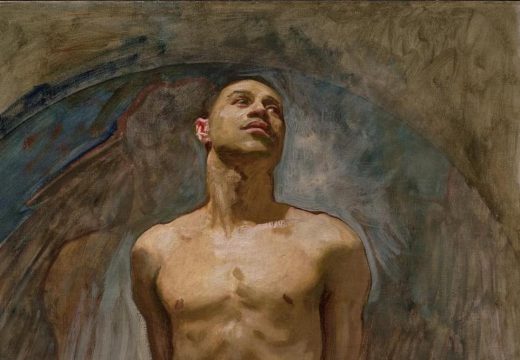

The MFA was also on to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism early – by 1920 it had eight Monets, and in 1936 acquired Gauguin’s undoubted masterpiece, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897–98) This was only a small part of the institution’s campaign to collect European paintings. To take just one example, the MFA acquired in 1901 the only Velázquez half as beguiling as the Prado’s Las Meninas. The Boston picture shows the two-year-old heir to the Spanish throne, Don Baltasar Carlos, in the company of a dwarf. The two figures echo one another’s stance and accoutrements, the diminutive jester holding an apple and a rattle – a visual rhyme for a kingly orb and sceptre. The dwarf is anonymous, but is portrayed by Velázquez as a fully rounded character, while the princeling is oddly flat. This raises the possibility that we are looking at a painting-within-a-painting; a break in the angle of the carpet pattern could be read as the edge of the canvas. I wrote a paper about all this as an undergraduate, and the painting still exerts a grip on my imagination to this day.

Don Baltasar Carlos with a Dwarf (1632), Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Of course, the MFA is not equally strong in all areas. As someone deeply involved in contemporary art, I have long been disappointed by its comparative weakness in this field – mainly the consequence of Boston’s self-conscious cultural conservatism relative to New York City, though competition from the local Institute of Contemporary Art, which is smaller and nimbler, probably hasn’t helped. Recently, however, the museum has managed to shake up its image with respect to current art practice, through the appointment of curator Reto Thüring. One of his first exhibitions for the MFA, ‘Contemporary Art: Five Propositions’, drew thoughtful connections across the institution’s modern and contemporary holdings, and included recent acquisitions from artists such as Simone Leigh and Vivian Suter, as well as a terrific commissioned installation by Lucy Dodd.

To be sure, as in any relationship, there have been some bumps along the way. Like many in the art world, I was appalled when, in 1999, then-director Malcolm Rogers abruptly fired 18 members of the museum’s staff, including Fairbanks – one of two long-serving curators, who, notwithstanding their seniority, were marched to their desks to collect their things and thence to the exit. It immediately became known as the ‘Boston Massacre’. Rogers also did some glorious things for the MFA over the course of his 21 years as director, delivering a comprehensive architectural renovation by Norman Foster and Partners. He dramatically increased attendance, albeit through exhibition programming that, in the words of local journalist Patti Hartigan writing in Boston Magazine, ‘recalled the location’s former use as a circus ground’. In 2005, there was a notorious outdoor display of two America’s Cup yachts owned by one of the museum’s patrons, Bill Koch.

Even five years after his retirement, Rogers remains a divisive figure. But any fair-minded person would have to say that the Museum of Fine Arts of today is a far more impressive, vibrant place than the one he inherited. Under his successor Matthew Teitelbaum, who arrived in 2015, the institution has built on this momentum, among other things by deepening its relationship to the local community, through a programme called ‘Table of Voices’. By its own admission, the museum has had to take big steps forward in terms of cultural awareness. Last year, after a school group of African-American children experienced racist behaviour by staff and two visitors, the MFA did not offer excuses but instead took concrete steps, immediately establishing a position for a senior director of inclusion and holding a series of roundtable discussions on the theme of diversity.

Linda Nochlin and Daisy (1973), Alice Neel. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo: courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner; © The Estate of Alice Neel

Also in 2019, to mark the centenary of the Nineteenth Amendment, Nonie Gadsden curated ‘Women Take the Floor’, installing the entire top floor of the museum’s American Wing with works by female artists. The presentation gives thrillingly high profile to craft-adjacent artists such as Sheila Hicks and Toshiko Takaezu and also provides the best of all possible contexts for Alice Neel’s portrait of Linda Nochlin, the feminist art historian best known for her provocative essay of 1971, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’. Neel’s masterly painting seems to provide an unspoken rejoinder: here’s one. In curating the display, Gadsden did not shy away from publicising statistics about ongoing gender disparity in the collection; this was not a moment of self-congratulation, but rather indication of the work that remains to be done.

All of which brings us, unavoidably, to now. This anniversary year should have been a big one for the MFA. Instead, like so many other institutions across the country and the world, it has had to close its doors due to the coronavirus pandemic. Another exhibition of Monet was planned – focusing on Boston’s own paintings – but no 17-year-olds will be seeing it (at least for now), nor will undergraduates be pressing their nose to the Chinese ceramic cases. The MFA’s outstanding Egyptian and Nubian collections are once again entombed. At the other end of the chronological spectrum, ‘Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip Hop Generation’, which bids fair to be the museum’s edgiest show of recent art in recent memory, was meant to open on 5 April. Like so many other long-planned projects, it will not go on view until the crisis has passed.

Shawabties of King Tarharqa (Napatan Period, reign of Taharqa, 690–664 BC), Nubian. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

I spoke with Ethan Lasser, head of the American department, about this situation in mid March, to find out how the museum’s staff was responding. His first thought was how strange it was to be separated from the collection: ‘We’re used to seeing certain art works on our everyday passages through the building. This may be the longest I’ve gone without seeing a work of art since I’ve been a curator.’ The only staff members still regularly allowed in the museum are the security guards, who are considered essential personnel, which, Lasser muses, ‘kind of puts you in your place’. It’s an example of what we are seeing throughout the economy. White-collar workers can do little more than shelter in place, while cleaners, nurses, homeless shelter staff, delivery drivers, and grocery checkout people are asked to become the heroes of the hour – though as Michelle Millar Fisher, curator of contemporary decorative arts, notes, they were heroes already: ‘Some of us are only noticing that now, perhaps. It is our perception that has changed, and also of ourselves and our powerlessness in the immediate moment.’

Early in the crisis, the MFA announced that it would continue to compensate all of its staff, whether salaried, hourly waged, or temporary. It also did what many other museums are doing, trying to share its collection from afar through social media – including promotion of existing YouTube content and regular posts on Instagram. Through those platforms one can still make discoveries in the MFA collection – for me, it is Pentagon (2011), a work by the Iranian artist Monir Farmanfarmaian, whose spiralling, fragmentary mirrored construction seems the perfect emblem for the widening gyre in which we all find ourselves adrift. Surely other, more substantive online initiatives will follow. It will be interesting to see, during this period of remote-only access, how the public responds. Will we witness the dawn of a new age for the ‘digital museum’? Or will this episode only confirm the museum’s role in society as a remaining bastion of IRL, in-person experience?

These questions are facing the whole museum sector, of course, not just the MFA Boston. But I can’t help thinking of the place right now – to imagine a single guard’s footsteps echoing in the galleries on a bright Tuesday afternoon. And it’s particularly worrying to think about what it may mean for my beloved hometown museum long-term – the immediate loss of revenue (not just admissions, but also shop, restaurant, even parking garage income), the disruption to forward planning. Together with the rest of us, the institution will be feeling the effects of the virus shutdown for months and years to come.

Whichever museum you happen to hold dearest, at this time, is going through its own version of this reality – with those that are smaller and less endowed at significantly greater risk. At such a time, it is worth emphasising both the fragility and the importance of them all. Even while their doors are shut, we should remember how much museums bring to our lives – the way that they remain there for us, even as we ourselves change. As one online commentator remarked, in response to the MFA’s announcement of its shutdown, ‘The threat of Covid-19 is real; but art is the bigger truth.’

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is currently closed. Visit the museum’s website for more information.

From the May 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home