From the June 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

‘If heaven had given me a few more years,’ Napoleon mused in exile on Saint Helena, ‘I would have made Paris the capital of the Universe.’ On the battlefield the emperor had often been as preoccupied with reshaping his capital as with expanding his empire’s borders. ‘I will make it the glory of my reign to have changed the face of the territory of my Empire,’ he wrote to his minister of the interior in 1807.

At his death in 1821, Napoleon’s dreams of transforming Paris to rival ancient Rome, which Augustus had found a city of brick and left as one of marble, were belatedly becoming facts on the ground as the restored monarchy carried forth many of his incomplete projects. Louis XVIII embraced Percier and Fontaine’s extensive transformation of the Louvre and Tuileries, noting that the emperor had been ‘a very good tenant’. And the Arc de Triomphe at the Étoile – the world’s tallest such structure when it was built – broadcast Napoleon’s ambitions long after his final defeat. A mere wooden mock-up when the emperor passed beneath it in 1810 with his new bride Marie-Louise of Austria, by 1840 it had been rebuilt in masonry and richly adorned with sculptures in time for Napoleon’s ashes to pass beneath en route for reburial at the Invalides.

Napoleon’s interventions in cities across the empire were to shape their growth for decades to come. As much as he lusted after colossal monuments – from the Vendôme Column, which soared high above the roof lines of the Place Vendôme, to the projected elephant fountain at the Bastille – it was the territorial scale of his city planning that transformed the localised practice of 18th-century urban embellishment into a technocratic means of urban administration. For a decade after the coup d’état of 1799, creating a great east-west axis connecting the Bastille to the Étoile remained a fixation; the beautiful regularity of Percier and Fontaine’s facades on the rue de Rivoli set over arcades modelled on those of Turin are its most scenographic segment.

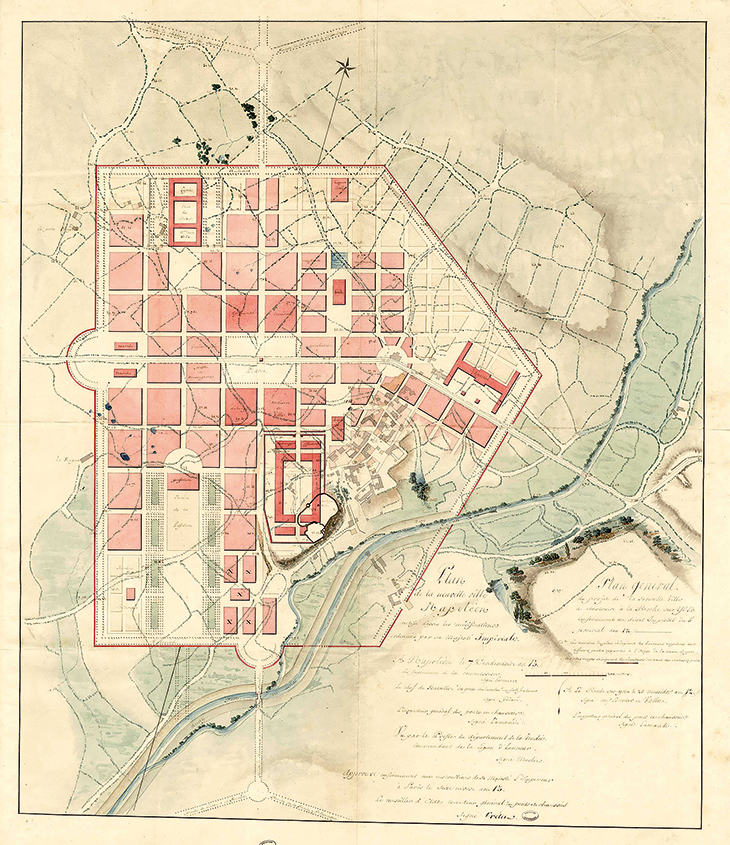

Plan for the creation of a new town, Napoléonville, to be built in La Roche-sur-Yon in the Vendée, as laid down by an imperial decree of May 1804 and revised in September that year. Archives nationales

After 1809, pragmatism gained the upper hand over rhetoric. ‘It is only when we have given Paris sewers, slaughterhouses, markets, and granaries, that we can undertake such a huge operation,’ Napoleon declared. Neighbourhood and wholesale markets, including a monumental wine district, were built; fountains flowing with potable water were installed in newly fashioned public squares; the Seine was embanked and crossed by new bridges, along with the creation of kilometres of repaved roads, street lighting, and a new rational system of house numbering. All were to make the capital a model of a city that could be run as efficiently as an army battalion.

The creation of the departments in 1800, in the wake of the adoption of the metric system, was at once an administrative rationalisation of territory and a wholesale practice of spatial logic and control. For the department of the Vendée, a region notorious for its resistance to the Revolution and Empire, the small town of La Roche-sur-Yon was not only to be renamed for Napoleon, but also extended with a gridded street plan centred on an open square to be lined with public buildings and featuring a large green esplanade, the Place Napoléon. It was both a military emplacement and a city without fortifications in which greenery and open spaces were integrated with regular blocks of harmonious buildings, the heights of which were carefully regulated. The town was crossed by a national route on the north-south axis.

Further north, along the planned Nantes-Brest canal that was to change both internal markets and the port network of the Atlantic seaboard, the small Breton town of Pontivy was also rebaptised Napoléonville. With plans drafted by designers from the corps of bridge and road engineers (Napoleon notoriously favoured no-nonsense engineers to architects, who he claimed had ruined Louis XIV), this Napoléonville was finally developed from a scheme refined by the engineer-turned-civic administrator Gaspard de Chabrol. Freshly returned from the scientific expedition of Egypt, Chabrol imagined a town that could represent the distant central power, accommodate half an army brigade, and provide for the needs of civilians and soldiers with a hospital, church and theatre, all to be built in an austere neo-classical style, as well as a botanical garden in a great hemicycle extension to the town’s grid. From here Chabrol was posted to conquered Liguria, where he worked on transforming the port of Savonne. When in 1812 he became prefect of the Seine, responsible for Paris, he took Napoléonville as a model for developing neighbourhood centres in the city’s reorganised arrondissements.

View of the projected Foro Bonaparte, Milan 1800 (c. 1800), Alessandro Sanquirico. Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne

As French armies racked up victories, Napoleon’s territorial conquests were accompanied by the conquest of urban space. Marching into Flanders, he stopped in Liège long enough to survey the city and order works including a new bell tower for the cathedral and modified fortifications. Urban schemes were projected from Madrid to Mainz, but his grandest visions were for Italy, as though he might continue the work of the ancient Romans. In Venice in 1807, the demolition of the church of San Geminiano regularised the Piazza San Marco with a fourth side, while the draining of new marshland endowed the city with its first public garden. But Milan was his first focus. The Foro Bonaparte – a type also proposed for Madrid – was to replace the old citadel and link city with countryside. A huge circular place, 570 metres in diameter, with a circumference of neo-classical buildings (worthy of Nash’s Regent’s Park) would house public functions – a people’s assembly, a centre for the arts and for sciences – alongside military barracks. As envisioned by the architect G.A. Antolini this perfect geometry integrated a vast park, a new type of garden city at the edge of the dense urban fabric and at the meeting point of three imperial roads with links to two navigable canals.

With the birth in 1811 of an heir, the king of Rome, Napoleon forged new links between the imperial capital in Paris and the Eternal City. One million francs were designated for embellishments to Rome, while Percier and Fontaine reimagined the western limits of Paris with a huge palace for the roi de Rome atop the heights of Chaillot and, on an axis across the Seine, a rationalised administrative quarter with university, archives, and a palace of the arts. Only the foundations for the palace had been laid when Napoleon abdicated. But by then he had suggested a direction for urban transformation that would be taken up by his nephew Napoleon III, four decades later.

From the June 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home