From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The Museo del Vetro on Murano houses, as one would expect, examples of glassmaking at its most virtuosic. Here, for instance, is a ewer shaped like one of the great galleys produced by the Venetian Republic’s Arsenale; there a strutting cockerel, its chest feathers puffed out, the front of its scarlet comb nodding jauntily over an orange beak; or overhead in the central hall of this palazzo, the extravagant chandeliers so closely associated with the island’s production – here triple-tiered like airborne wedding cakes. But among these elaborate forms, just as curious and compelling are some of the surface effects achieved by the Muranese maestri. It’s a sure sign that a craft has been well and truly mastered when the medium in question is made to look like another one altogether: glass masquerading as opal, onyx or malachite. In the 15th century, glassmakers began adding tin oxide to some of their batches to produce an opaque white glass that could resemble prized Chinese porcelain. Lattimo, as the effect was called, from latte, enjoyed a resurgence in the 18th century (this time made with arsenic), spurred by the proliferation of European-made porcelain. Hence a large vitrine in the museum of what I mistook for ceramics: milk-white vessels decorated with rococo mythological scenes or elements of chinoiserie.

Downstairs, the exhibition ‘One Hundred Years of Nason Moretti: The Story of a Murano Glass Family’ (until 6 January 2024) neatly demonstrates how these techniques – some of them forgotten and then rediscovered over the years – have been translated for the 20th and 21st centuries. Nason Moretti was founded in 1923 with, as co-curator Cristina Beltrami writes in an elegant accompanying book, ‘an eye on the semi-mechanical realities of northern Europe’. The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, held in Paris in 1925, was just around the corner. The company’s aim, a deceptively bold one given the fierce tradition of Murano as a producer of exceptional objects at high cost, was the ‘manufacture of ordinary glassware’. It would make use of moulds to streamline production and allow for wider distribution, but without compromising on quality: glass was and is still blown, and not pressed, in the mould.

The results of this modern – even modernist – approach are set out in the exhibition like so many pieces of confectionary in an exceptionally chic sweetshop. Here again is that joy in material imitation, or evocation. Art deco’s taste for luxurious (or fictively luxurious) materials perhaps accounts for an opaque black-and-red liqueur service made in the mid 1920s from lacquer-like vitreous paste; Gabriele d’Annunzio bought a set, as well as an ice-cream service, for his idiosyncratic villa overlooking Lake Garda.

A bowl from the ‘Lidia’ series designed in 1954 by the Murano glassware company Nason Moretti. Photo: © Studio Pointer

The most delicate porcelain, meanwhile, is recalled in a series of glasses and bowls designed in 1954 by Umberto Nason, one of the company’s five founder brothers, here set apart to mark a highpoint in the glassworks’ history. The ‘Lidia’ service employs the incamiciato technique – literally translating as ‘shirted’, where a thin layer of lattimo glass is ‘encased’ in a layer of transparent coloured glass, allowing for a rich if subtle play of colour between the two. In this design, however, the usual approach has been reversed, so that rather than lining the interior of the vessel, the lattimo glass coats the outside, leaving the colour – whether yellow, red, blue, green, amethyst or light brown – to occupy the interior (technically a more challenging method of production). In 1955 ‘Lidia’ won the Compasso d’Oro, a design award that had been established the previous year by Gio Ponti and still runs today. Soon after, the service was featured in Ponti’s influential magazine Domus, and exhibited with other designs from the competition in New York – which is probably where it caught the attention of the architect Philip Johnson, who donated 18 pieces from the series to MoMA.

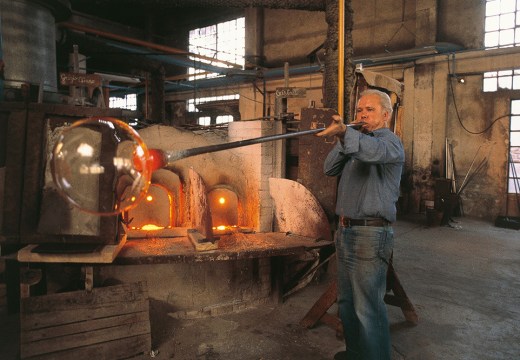

Now run by another generation of the same family, Nason Moretti’s waterfront glassworks is a 15-minute walk from the Museo del Vetro. Along one exterior wall at the back of the 1920s building is an arresting sight: a pitchfork propped up in a brick stall as if in a stableyard, ready to shovel not hay or manure but the glossy fragments of coloured glass that have been piled up here, each in their own labelled stall: giallo, verdogno, verde pino, rosso, blu cento, aragosta. Around 30 per cent of Nason Moretti’s production is made from recycled glass, a growing trend on Murano generally.

Inside, glassblowers work in their different piazze, coaxing fiery molten forms into something miraculously crystal to sight and touch. Purple-stemmed goblets and opaline-blue water glasses inch through a machine on a conveyor belt, to be cooled over a period of four hours to prevent cracking. Then comes cutting, finishing and polishing. I’m put in mind again of the ships that emerged sometimes daily from the Arsenale in its heyday, anticipating the modern production line by centuries. This too is a production line – just one that involves an extraordinary level of skill and craftsmanship.

From the November 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home