Biographies rarely do the trick. Quite simply, they are not the best means by which to restore an artist’s reputation. Michael Holroyd’s two-volume life of Augustus John (1974) made for compulsive reading, but gave only a momentary lift to John’s artistic reputation. Andrew Lambirth, in this well-illustrated monograph, forswears biography and keeps John Nash’s art very much to the fore, yet provides a rounded portrait of his life, character and relationships. It is a considerable achievement. Lambirth has brought to his study of Nash a similar depth of scholarship to that found in Andrew Causey’s two monographs dedicated to his brother Paul. But as Nash outlived his brother by 30 years there has been more ground to cover, and in the course of telling us much about Nash’s social and artistic world, Lambirth reanimates not only this artist but many others within the history of 20th-century landscape painting.

Because his elder brother was always drawing, Nash began to do the same as a child. But he did not follow his brother to the Slade School of Art; Paul advised against it, recognising that academic study might destroy his brother’s authentic naivety. Both he and his friend, the poet Gordon Bottomley, admired the poetic charm in Nash’s art and what Bottomley termed its ‘vivid actuality’. But, as Lambirth recounts, it was the sight of one particular watercolour that sent Paul to his father to announce that Nash was definitely an artist and nothing should prevent him from pursuing this career. As Nash’s skill at painting increased, his art became more orthodox, but it retained a refreshing simplicity of vision.

Lambirth tells how the two brothers held their first solo exhibition together in 1913, but fails to mention that they had already attracted attention at the Allied Artists’ Association’s annual exhibitions at the Royal Albert Hall. Here they became known to Harold Gilman and Spencer Gore, who were members of the Camden Town Group. When the latter merged in 1913 with the Vorticists to form the London Group, Nash found himself one of the founder members, whereas his brother was not elected until the following year. John was also invited to join the Cumberland Market Group in 1915, of which Gilman was a leading figure. He became a mentor to Nash, urging him to move from watercolour to oil, to draw on the spot but to paint in the studio. This swift and brilliant start to Nash’s career was interrupted by the onset of war. He remained exempt from military service until after the Somme offensive, when the need for more men lowered the standards of physical health expected of a soldier. On reaching the Front, he experienced landscapes torn and blasted by war, nature in a painfully different form.

Moonlight Landscape (c. 1914), John Nash. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven; © Estate of John Nash

When Nash was released from service in order to take on the role of war artist, the subjects he painted unsurprisingly showed a new hardness and edge. But just as forceful are some of the landscapes he painted after the return to peace, such as The Cornfield (1918), or the almost hallucinatory Dismantled Wood (c. 1920), both offering an affirmation of the continuity and new life associated with nature. In 1918 John married Christine Kuhlenthal, a former Slade student who gave up her own painting in order to create what Ronald Blythe has described as ‘the somewhat strict environment required for his life and art’. It was Nash’s habit to take working holidays every summer, after Christine had made preliminary trips to discover a new place that offered good things to paint. Their shared life proved remarkably stable, despite their mutual agreement that marriage could accommodate sexual infidelity, of which there was plenty. After many years of marriage they had a son, who tragically died at the age of four when a door of their car fell open and he slid out of his seat and hit his head on a metal drain cover. Lambirth mentions this in passing, but leaves this and other matters to Andy Friend, who is currently at work on Nash’s biography.

The Cornfield (1918), John Nash. © Tate, London, 2019

Lambirth does, however, supply useful information on other aspects of the Nashes’ lives: their friendship with the painter Peter Coker and his wife Vera; Nash’s association with Clarence Elliott, one of the most influential horticulturalists of the period; and the Nashes’ unofficial adoption of Blythe, who eventually inherited Bottengoms, their final house at Wormingford, and who has documented much about their lives. Also welcome, in this occasionally disordered book, is Lambirth’s careful attention to Nash’s exhibition history and to his steady gain in recognition. He eventually became a Royal Academician, and the first to be granted a solo exhibition at Burlington House. En route he developed a passion for plants and acquired great skill as a wood engraver, becoming a superb illustrator of flowers. His finest book in this vein is Poisonous Plants, Deadly, Dangerous and Suspect (1927). As Lambirth points out, it carries scant text because the images are so self-sufficient. Nash liked to call himself an ‘artist plantsman’, to underline the significance to his landscape painting of his study of horticulture, for his love of plants enabled him to catch nature’s rhythm and pulse.

Summer Flower Piece (1930s), John Nash. Government Art Collection; © Estate of John Nash

Lambirth revives Nash’s stature as an artist. After his death in 1977 he slipped into the shadows. There have in fact been several previous publications on Nash but all have focused on aspects of his life or work and none has given us the full picture. Paul Nash’s towering reputation has also left John underappreciated and overshadowed. Gilbert Spencer suffered likewise, in relation to his brother Stanley. Not surprisingly he and Nash became close friends, each acting as the other’s best man when they married. Lambirth not only successfully integrates Nash’s life and art, but he brings to the fore a different set of virtues from those that belonged to his more cerebral and restlessly ambitious older brother. It is good to be reminded that Nash might never have become a painter without Paul’s encouragement. The two brothers were always very close and Lambirth scotches the notion that they fell out and broke off relations in later life, citing their correspondence to show how mutual brotherly affection was retained to the end. What unites them is the way they opened up a new sensibility towards landscape and broadened our perception of it – much of this during a period when patterns of agriculture were changing irrevocably. It is in no small part due to them that many still look to landscape for an emollient to the instability of urban life.

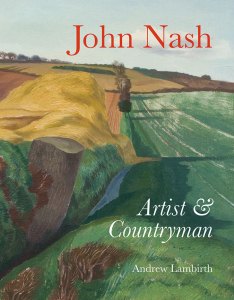

John Nash: Artist & Countryman by Andrew Lambirth is published by Unicorn Press.

From the February 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home