At first sight, there is nothing very unexpected about Elements Number 30, an assembly of sheet-metal units and steel girders, which is the first object visitors see on their way to the upper galleries of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It is only when you read a discreet wall label that you discover that it is on display with an extra art-historical purpose. The sculpture is by the Iranian-born Siah Armajani and the label ends: ‘This work is by an artist from a nation whose citizens are being denied entry into the United States, according to a presidential executive order issued on January 27. This is one of several such art works from the Museum’s collection recently installed, along with others throughout the fifth-floor galleries, to affirm the ideals of welcome and freedom as vital to this Museum, as they are to the United States.’

This is an act of guerrilla curating, a rapid response to President Trump’s now legally stalled ban on visitors to the US from seven mainly Muslim countries: Iran, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, and Sudan. Trump’s disruption of international travel has been matched by the disruption of the linear progression of Modernism, set in stone by MoMA’s founder director Alfred Barr. Thus the Iraqi-born Zaha Hadid’s painting The Peak, Hong Kong, China (1991) now hangs beside Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy (1897) and Edvard Munch’s The Storm (1893).

Other than the polemical labels, there is nothing to point the visitor to these interruptions, so it becomes a refreshing game of to spot these supposed interlopers from MoMA’s own collection. The hang has been done with great flair. The Iranian-American Marcos Grigorian’s striking Untitled (1963), a composition of dried earth that alludes to the sand and soil of Iranian village life, sits well with Antoni Tapies’s brown and black abstract Space (1965) and the charred sacking of Alberto Burrri’s Sackcloth (1953).

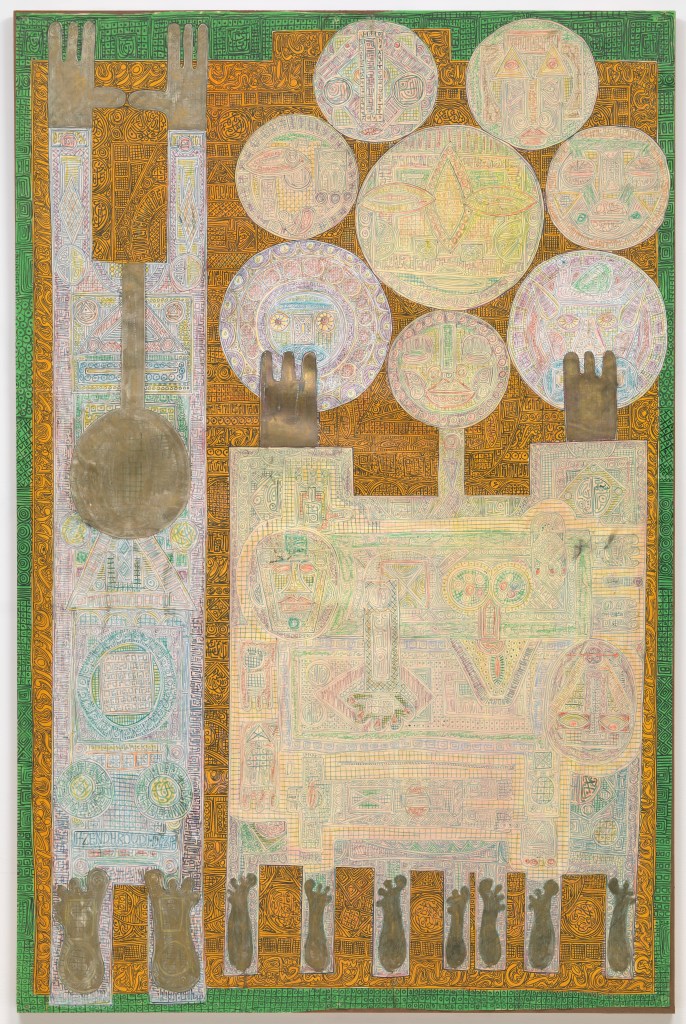

K+L+32+H+4. Mon père et moi (My Father and I) , (1962), Charles Hossein Zenderoudi. Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, NY

The compliment of sharing a space with Matisse’s Dance 1 (1909) goes to the Iranian Charles Hossein Zenderoudi’s K+L+32+H+4 Mon père et moi (1962), a felt-tip semi-abstract portrait that uses motifs from Tehran bazaars, Shiite iconography, and sacred calligraphy. The gouache, metallic paint and stamped gold and silver paper of Laminations (Les Lames) (1962) by fellow member of the 1960s Iranian Saqqakheh school is in full harmony with Clyfford Still’s 1944-N No 2 (1944) that hangs beside it.

While MoMA has struck a chord with this changing display of ‘excluded’ artists, the Director of the Metropolitan Museum, Thomas Campbell, British-born but now an American citizen, has commented on the attempted travel ban that has affected members of his own staff in a forceful blog. He writes: ‘It is vital for the public to have a credible, rational, and thoughtful context to understand where we are and how we got there.’ He points out that the Met opened its Islamic Galleries in 2011, ten years after 9/11, and that they serve as ‘a counterpoint to the over-simplification of Islam prevalent in today’s media and political discourse’.

The need for rational thought and resistance to over-simplification is a sentiment I have encountered many times in New York. The architecture students at Columbia University have responded more tersely. They have filled the windows of their studio with the message WE WILL NOT BUILD YOUR WALL. As the disruptive effects of Brexit begin to become clear, can we expect a response like MoMA’s and the Met’s from British institutions?

New York’s leading museums are insisting on their internationalism

The Peak Project, Hong Kong, China , (1991), Zaha Hadid. © Zaha Hadid

Share

At first sight, there is nothing very unexpected about Elements Number 30, an assembly of sheet-metal units and steel girders, which is the first object visitors see on their way to the upper galleries of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It is only when you read a discreet wall label that you discover that it is on display with an extra art-historical purpose. The sculpture is by the Iranian-born Siah Armajani and the label ends: ‘This work is by an artist from a nation whose citizens are being denied entry into the United States, according to a presidential executive order issued on January 27. This is one of several such art works from the Museum’s collection recently installed, along with others throughout the fifth-floor galleries, to affirm the ideals of welcome and freedom as vital to this Museum, as they are to the United States.’

This is an act of guerrilla curating, a rapid response to President Trump’s now legally stalled ban on visitors to the US from seven mainly Muslim countries: Iran, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Yemen, and Sudan. Trump’s disruption of international travel has been matched by the disruption of the linear progression of Modernism, set in stone by MoMA’s founder director Alfred Barr. Thus the Iraqi-born Zaha Hadid’s painting The Peak, Hong Kong, China (1991) now hangs beside Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy (1897) and Edvard Munch’s The Storm (1893).

Other than the polemical labels, there is nothing to point the visitor to these interruptions, so it becomes a refreshing game of to spot these supposed interlopers from MoMA’s own collection. The hang has been done with great flair. The Iranian-American Marcos Grigorian’s striking Untitled (1963), a composition of dried earth that alludes to the sand and soil of Iranian village life, sits well with Antoni Tapies’s brown and black abstract Space (1965) and the charred sacking of Alberto Burrri’s Sackcloth (1953).

K+L+32+H+4. Mon père et moi (My Father and I) , (1962), Charles Hossein Zenderoudi. Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, NY

The compliment of sharing a space with Matisse’s Dance 1 (1909) goes to the Iranian Charles Hossein Zenderoudi’s K+L+32+H+4 Mon père et moi (1962), a felt-tip semi-abstract portrait that uses motifs from Tehran bazaars, Shiite iconography, and sacred calligraphy. The gouache, metallic paint and stamped gold and silver paper of Laminations (Les Lames) (1962) by fellow member of the 1960s Iranian Saqqakheh school is in full harmony with Clyfford Still’s 1944-N No 2 (1944) that hangs beside it.

While MoMA has struck a chord with this changing display of ‘excluded’ artists, the Director of the Metropolitan Museum, Thomas Campbell, British-born but now an American citizen, has commented on the attempted travel ban that has affected members of his own staff in a forceful blog. He writes: ‘It is vital for the public to have a credible, rational, and thoughtful context to understand where we are and how we got there.’ He points out that the Met opened its Islamic Galleries in 2011, ten years after 9/11, and that they serve as ‘a counterpoint to the over-simplification of Islam prevalent in today’s media and political discourse’.

The need for rational thought and resistance to over-simplification is a sentiment I have encountered many times in New York. The architecture students at Columbia University have responded more tersely. They have filled the windows of their studio with the message WE WILL NOT BUILD YOUR WALL. As the disruptive effects of Brexit begin to become clear, can we expect a response like MoMA’s and the Met’s from British institutions?

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

Treasures from Palmyra preserved in the world’s museums

As ISIS destroys the site, these items are more important than ever

Zaha Hadid’s death leaves British architecture immeasurably poorer

The UK was slow to appreciate Zaha Hadid’s uncompromising attitude to architecture, but she was one of the most important British architects of the past 100 years

Trouble ahead for New York’s museums

After years of expansion, funding is a major issue for the city’s museums. How will they fare if the Trump administration provokes fresh culture wars?