This review of Noble Ambitions: The Fall and Rise of the Post-War Country House by Adrian Tinniswood first appeared in the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In February 2014, the Kettering-based neo-psychedelic rock band Temples released their first studio album Sun Structures. Temples conjured the spirit of the late 1960s not just through their music style, haircuts and fashion choices, but also through their choice of album cover art. The four band members stand in front of the Rushton Triangular Lodge, designed by Sir Thomas Tresham and constructed between 1593 and 1597. This kind of posing in front of gothic follies has a rich rock ’n’ roll lineage. In the summer of 1968, for instance, the Rolling Stones could be found hanging out of the mullion windows of the Swarkestone Pavilion (now in the care of the Landmark Trust) for the photo shoot for their album Beggars Banquet.

This vignette – Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Bill Wyman, Brian Jones and Charlie Watts dressed up as medieval troubadours – captures the essence of Adrian Tinniswood’s exploration of country house life in the three decades between the end of the Second World War and the ‘Destruction of the Country House’ exhibition at the V&A in 1974. Noble Ambitions charts the ways in which traditional rural values collided with both the socially and sexually adventurous world of Swinging London and – more prosaically – the newly mobile middle classes with weekends to fill and places to visit.

Edward, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu scrubbing floors in Palace House in 1952. Photo: National Motor Museum/Heritage Images via Getty Images

These years up to 1974 have been well studied by historians of the country house, the pages of whose books are full of heroic aristocrat-entrepreneurs such as Lord Montagu at Beaulieu and the Duke of Bedford at Woburn who gamely found a way to keep the show on the road. While these characters both feature in Noble Ambitions, Tinniswood uses them to tell an alternative story of country house life, one characterised less by despair and destruction than by a dynamic engagement with the changing nature of post-war Britain. Rather than donning rose-tinted spectacles and adopting an elegiac tone, Tinniswood’s springy prose is clear-eyed when it comes to analysing the self-interest that lies at the heart of country house life. Instead of being passive victims of an increasingly meritocratic society, the owners of country houses that populate the pages of Noble Ambitions come out fighting when inheritance tax threatens, demolish wings and stable blocks of their ancestral homes when surplus to requirement, and get caught up in every manner of sex scandal. Crucially, this book looks beyond the ‘notable’ country houses beloved of architectural historians and preservationists, to consider how in places such as Ham Spray, on the border of Wiltshire and Berkshire, country house life continued oblivious to royal commissions and negotiations with the Treasury.

Tinniswood’s eye for a juicy anecdote provides the raw material for the book’s 20 chapters. Three tribes dominate: families with ancestral estates, hordes of agricultural tenants and the crippling weight of centuries of tradition; those whose considerable wealth from commercial investments enabled a luxurious lifestyle in huge houses (often without countless additional acres); and new visitors to these properties – from tourists to house-party guests. Noble Ambitions is at its most enjoyable when these three groups meet in unexpected configurations.

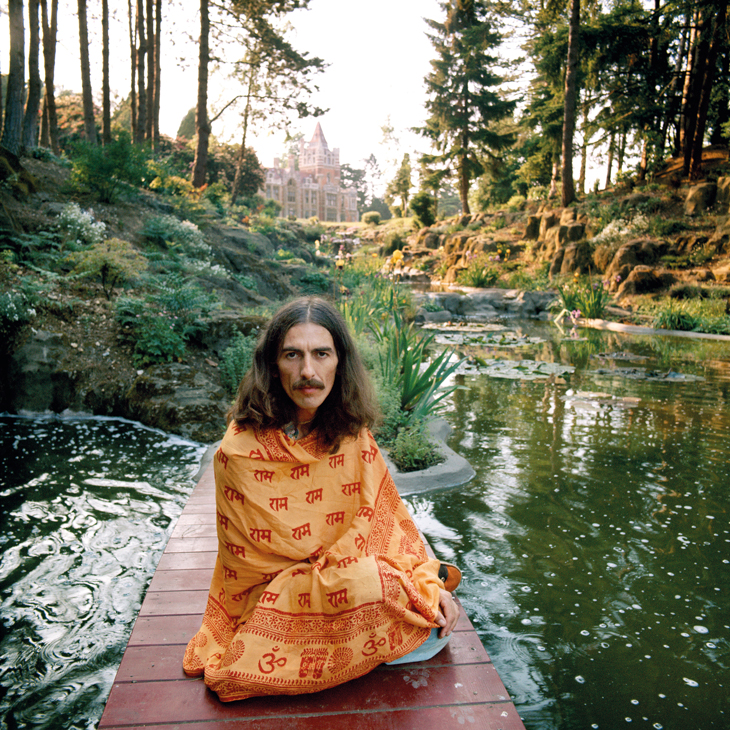

George Harrison photographed by Terry O’Neill in the grounds of Friar Park in Oxfordshire in 1975. Photo: © Terry O’Neill/Iconic Images

At Luggala in 1966, for example, Oonagh, Lady Oranmore and Browne (née Guinness), hosted a 21st birthday party for her son Tara that combined the traditional (a speech from Luggala’s estate manager on behalf of the estate workers) with the hyper contemporary. The interior decorator David Mlinaric decked out the marquee, and two guests locked Mick Jagger in the service courtyard, having been convinced he was the devil thanks to a particularly bad acid trip. Tinniswood extrapolates from a slew of self-indulgent rock star autobiographies (all listed in the bibliography for the curious reader) the prominence of country houses in 1960s and ’70s music. Keith Richards, ‘poncing around in my Bentley’ as he puts it, purchased Redlands, a 16th-century timber-framed house in West Sussex, which would later be the scene of the Stones’ infamous drugs bust. We learn that Eric Clapton was an avid reader of Country Life, which is where he found his new home, Hurtwood Edge in Surrey, and how Tittenhurst Park, owned by John Lennon, played a starring role in the video for ‘Imagine’, as John and Yoko walk slowly towards the white stuccoed entrance before reappearing at the piano in the long bow-windowed drawing room. (Keeping it in the Beatles, Tittenhurst’s subsequent owner was Ringo Starr.)

Other aristocrats added lions instead of rock stars into the mix. Lord Bath at Longleat was introduced to the circus entrepreneur Jimmy Chipperfield in 1964. Bath was looking to increase visitor numbers, Chipperfield to make a load of cash. Together they formed a partnership, with Bath providing the fences and roads through the Capability Brown-designed park and Chipperfield the lions. In an intriguing post-imperial twist, the lions were sourced from Kenya, while the chain-link fencing came from military surplus originally ordered to defend military bases during the Mau Mau uprising. In 1970, Bath was at Woburn, where the Duke of Bedford had similarly sourced lions, rhinos, elephants, cheetahs, giraffes and monkeys from Chipperfield for his own safari park. As Lord Bath cut the ribbon to declare his fellow aristocrat’s attraction open, a baby elephant trod on his foot.

Other aristocrats added lions instead of rock stars into the mix. Lord Bath at Longleat was introduced to the circus entrepreneur Jimmy Chipperfield in 1964. Bath was looking to increase visitor numbers, Chipperfield to make a load of cash. Together they formed a partnership, with Bath providing the fences and roads through the Capability Brown-designed park and Chipperfield the lions. In an intriguing post-imperial twist, the lions were sourced from Kenya, while the chain-link fencing came from military surplus originally ordered to defend military bases during the Mau Mau uprising. In 1970, Bath was at Woburn, where the Duke of Bedford had similarly sourced lions, rhinos, elephants, cheetahs, giraffes and monkeys from Chipperfield for his own safari park. As Lord Bath cut the ribbon to declare his fellow aristocrat’s attraction open, a baby elephant trod on his foot.

The meeting of old and new – in social mores, politics, sources of wealth – animates Noble Ambitions. It is in some ways fitting that relics of this particular moment in the history of the country house are now museum pieces. At Shugborough Hall, National Trust visitors can explore ‘The Lichfield Apartments’, formerly leased by Patrick Lichfield, who underwent a metamorphosis each weekend ‘from being a photographer to being a landowner’ by driving up the M1. Today, visitors can choose between ‘relaxing on the settee watching a bit of television’ or being ‘lured by the smell of coffee into the kitchen and the chance to have a read and a sit down at Patrick Lichfield’s breakfast table’.

Noble Ambitions: The Fall and Rise of the Post-War Country House by Adrian Tinniswood is published by Jonathan Cape.

From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home