Omar Kholeif talks to Apollo about curating a major exhibition looking at the impact of digital technologies on artists, and about his long-term goals as the newly appointed Manilow Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago

‘Electronic Superhighway’ is a major exhibition dedicated to the impact of computer and digital technologies on artists. What makes this show timely now?

2016 feels like the perfect time for it: it’s the 50th anniversary of a series of events that happened at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York called ‘9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering’, which saw Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Yvonne Rainer, and other artists collaborate with engineers from Bell Laboratories on performances that stretched the parameters of the technologies of the time. The following year, 1967, that collective constituted themselves as a not-for-profit called E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), and that was the same year that the ARPANET papers were published – the starting point for what would become the internet, the network of all networks.

I’ve always been interested in artists who stretch the formal limits of technology, or who use it counterintuitively. In recent years, there’s been a lot of discussion that places artists in a post-internet context: I wanted to link that back to a broader historical genealogy.

Seduction of a Cyborg (1994), Lynn Hershman Leeson (b. 1941), DVD with sound, still image, 6.48mins. © (2015) ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe

The exhibition reverses chronology, travelling back from 2016 towards early experimental work in the field. What lay behind this curatorial decision?

The internet has been such a transformative context for art that simply to map a route to the present would have been a rather dry way to approach the subject. Instead, this exhibition will begin with the present, in the ground-floor gallery – you’ll feel as if you’re walking into a cloud full of interlaced or overlaid narratives, some of which connect thematically or aesthetically, some of which are completely contradictory.

Moving upstairs, the exhibition travels back into the 1990s, with a selection of net artworks, exploring how artists used the web browser as an interactive space; then into the ’80s and ’70s, in which artists such as Judith Barry and Lynn Hershman Leeson tackled different forms of interactivity; and finally into the ’60s. One of the key works from that period is a piece by Allan Kaprow called Hello (1969). It was an interlinked performance across public service television stations, where different artists, including Kaprow, were saying ‘Hello, I see you’ to each other – the idea was that it connected artists across different sites in real time.

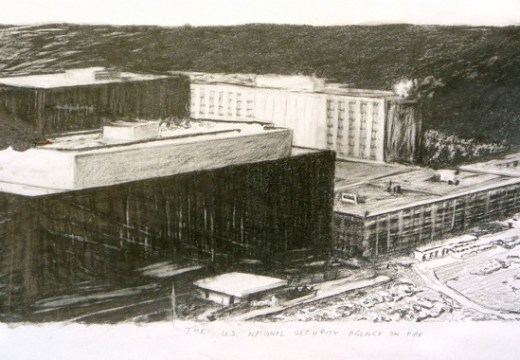

That concept also constitutes a theoretical backbone to the work of Nam June Paik, who lends the exhibition its title. ‘Electronic Superhighway’ was a term that he coined in an article in 1976, in which he was foretelling the effects of television, and its ability to unify people. A few years later in 1984, he created a performance called Good Morning Mr Orwell, which was the first networked international satellite performance. It’s been exciting trying to link together all these different historical moments.

Many of these works act as vectors for ideas about information or connectivity. But do some also have an aesthetic value for you?

Of course – and that’s partly because this is not just an exhibition of interactive screen-based works, but one that includes photography, sculpture, painting, and installation. I wanted to think, for example, about how artists have appropriated content from the internet to make paintings – artists such as Petra Cortright or Celia Hempton. A lot of the artists in the show aren’t just trying to unfold the significance of computer and internet technologies, but are also very concerned about why this work should belong in a gallery. Trevor Paglen, for instance, is very much inspired by the history of post-minimalist sculpture.

Aldo and Jesi, Albania, 16th August 2014 (2014), Celia Hempton (b. 1981), oil on canvas, 30 × 25cm. © Lynn Hershman Leeson / © Celia Hempton

How much guidance do visitors need through an exhibition of this nature?

I don’t believe that viewers will need a tremendous amount of guidance, because the material form of so much of the work will be completely familiar to them. Many of these artists appropriate everyday tools and then try to stretch them into new directions – as with Constant Dullaart’s reworking of the first Photoshopped photograph in Jennifer in Paradise. I’ve tried to make visual connections but not be overly didactic, and to make sure that the show leaves some room for the imagination to wander.

What makes the Whitechapel Gallery an appropriate venue for this exhibition?

The Whitechapel is a historic institution that’s known for firsts – exhibitions of Jackson Pollock or Frida Kahlo, for instance – and so it seems right that it should be the place to stage the first historic survey of art that uses internet technologies. And the gallery has always shown artists who are deeply invested in the history of technology, with exhibitions of Bruce Nauman, Gary Hill, or Chris Marker, or with group shows such as ‘This is Tomorrow’: it has always been engaged with how artists respond to the context of the future, and how they critically explore new technologies.

You’ve recently been named the Manilow Senior Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. What ambitions do you have for exhibitions and projects there?

For me, Chicago is the centre of America; the great American industrial city. It is closely associated with incredible histories of modernism, and with the history of modern and contemporary American architecture. It’s a kind of blueprint city, where things begin and emerge. Within that, the MCA is an institution that has also had its fair share of landmark events, such as Mona Hatoum’s first American museum exhibition in the ’90s and Doris Salcedo’s first ever retrospective in 2015. I want to continue in that vein of thinking of firsts – bringing in artists who have never shown in the US before, and creating group exhibitions that explore parallel histories of both modern and contemporary art – narratives that have perhaps been marginalised, or not properly documented.

What excites you most about the Chicago art scene?

I think of Chicago as the Berlin of North America. It’s a metropolis, but it is also a relaxed city, and yet there are always so many things happening. So many artists are based here – global figures who live and work in the city year round. There’s a huge intellectual community, and the Art Institute, the Renaissance Society, the Logan Center, the Smart Museum, the Field Museum…there’s so much culture to bed oneself into.

‘Electronic Superhighway’ is at the Whitechapel Gallery from 29 January to 15 May.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home