Tom Hammick knows about painting in the night. He works through the night in his studio. Apart from anything else there are not enough hours in the day for Hammick to both teach (at the University of Brighton) and to paint his own luminous canvases. The night is in them, and in him – as proven by the exhibition he has curated across five galleries in the Towner, Eastbourne. Through the work of over 60 artists, he takes us on a personal nocturnal journey.

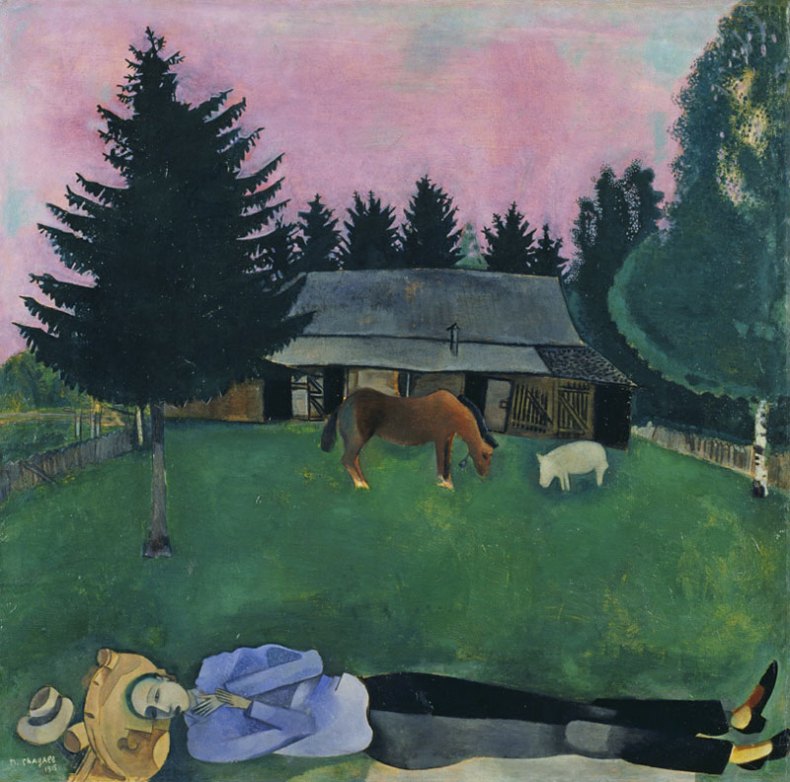

In the metaphorical twilight of the first room, Chagall’s The Poet Reclining (1915) can be found partying with two 18th-century Indian miniatures and a Julian Opie. In the second room the blue walls darken, but the shade of the background goes almost unnoticed by the visitor-dreamers, who are now feasting on the visions of Caspar David Friedrich and Ken Kiff, and the swelling seas of Turner and Nolde.

The Poet Reclining (1915), Marc Chagall. Photo © Tate, London 2016. Chagall ® / ©ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016

In the heat of the night, in room three, you are brought face to face with an American policeman shouting out over the edge of a still black lake. Some yards up the bank the lights of his abandoned panda car are flashing out of sync and out of feeling with the starry void. This Peter Doig fills one wall and overcomes the room – and Hammick, as a painter, must compete with him.

In the next room, the mood is gentler but no less challenging. Prunella Clough’s False Flower (1993) questions the paths we choose while Edvard Munch shows us how easy life can be if we surrender to our terrors and desires. The lovers in his Kiss (1902) are silhouetted against the grain of the woodcut: this stream of life shows through where the heads and mouths merge.

False Flower (1993), Prunella Clough. © Tate London 2016 © Estate of Prunella Clough. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2016

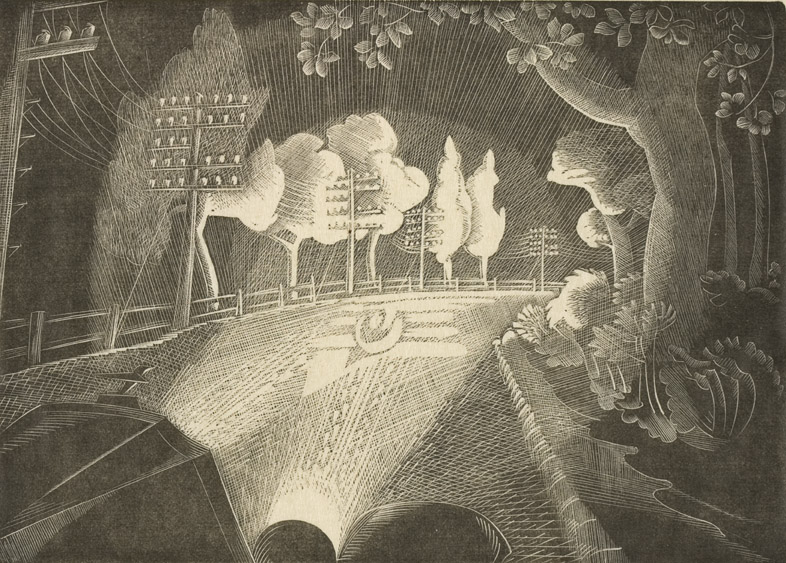

Concluding the exhibition in the fifth room is Howard Hodgkin’s Black as Egypt’s Night (2005–13), but the magic of the show is not in single paintings, but the whole journey. At one point he lines up three very different road pictures (a woodcut by Gertrude Hermes from 1929, a small but thickly painted Gas Truck by Nick Bodimeade from 2001, and a petrol station by Susie Hamilton from 1996) and one senses the mental road he has set us on. In his studio, he has pinned up his favourite pictures to remember while he works. Each gallery at the Towner represents a different stage of his nightly trips around his mind.

Through the Windscreen (1929), Gertrude Hermes. © Gertrude Hermes Estate

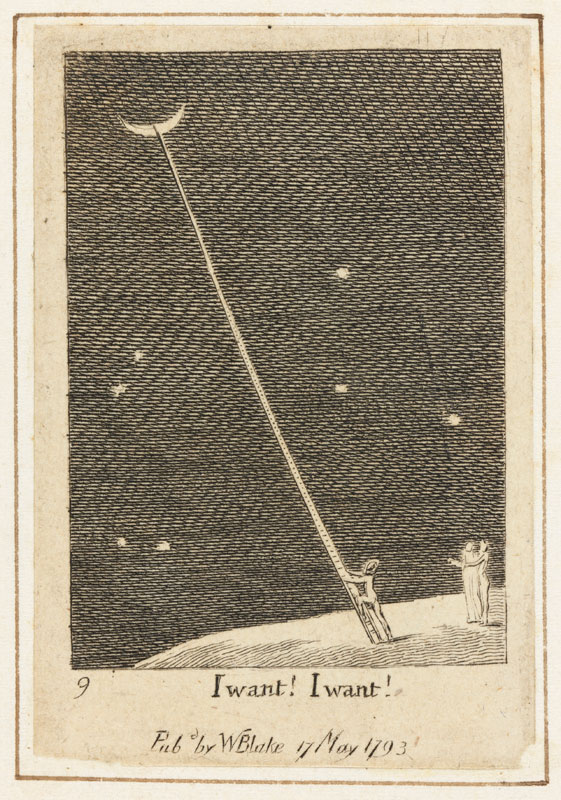

In his catalogue introduction, the artist quotes Virginia Woolf: ‘The evening hour too gives us the irresponsibility which darkness and lamplight bestow. We are no longer quite ourselves.’ I would argue that Hammick is very much himself at night. He is as much of a night painter as Lucian Freud was, yet there is no Freud, nor any other core School of London artist in this exhibition. Though there are works by the biggest names in painting, the aim is not simply to show painting off; it is rather a display of what makes Hammick the artist he is. He starts with Chagall as he is a poetic painter. He spotlights works by artists with an interest in literature, such as a little but powerful etching from 1793 by William Blake, of a man trying to reach the moon – ‘I want, I want’. This dream-like desire and sense of curiosity recurs again and again.

I want, I want (c. 1793–1818), William Blake. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

I fell foul of the ready confusion between literature and art at the packed opening by accusing Hammick’s mother, Georgina the writer, of being her twin sister, the artist Amanda Vesey. I compounded this later by mistaking the aunt for the mother. As Hammick admits his art comes out of the divisions in our world: ‘I often use night as a motif, as a way of pulling out what seems important from the shadow of darkness.’ He shows us how Ken Kiff did this before him in works like Tree by the River (1994), but as a painter he does not let himself wallow in the same Jungian anxiety about the battle between the feminine and masculine, between night and day. Nor does he totally embrace painter Andrzej Jackowski’s sense of reverie, which Hammick describes as a ‘hypnagogic world between waking and sleep…conveyed in his paintings and prints by an otherworldly radiance’. Instead he contrasts the artist’s work beautifully with a drawing and drypoint by Louise Bourgeois about insomnia.

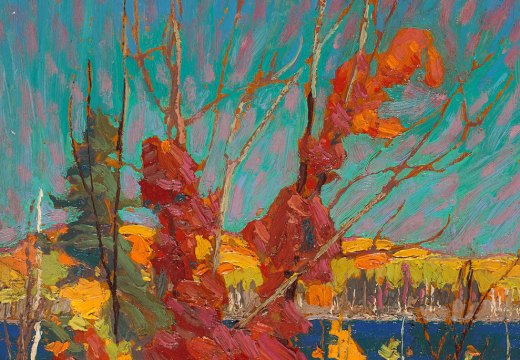

Artists use and adapt other artists’ ideas. If they are ambitious they do not take them whole. This is a brave display as it demonstrates Hammick’s willingness to confront his demons, and challenge the artists he most admires. The dream sequence that came away with me at the end of this show is of Hammick standing by heavy black waves of thought – grappling with the legacy of Nolde, Turner, and most difficult of them all for him, Doig.

‘Towards Night’ is at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, until 22 January 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home