Brush in hand, delineating the collar of a portrait of Queen Marie Antoinette, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) greets visitors to her retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris. Her face is set against the plain dark background of her self-portrait, a welcoming smile illuminating her features. A few strokes of white suggest the moistness of her lower lip, imbuing her with sensuality. Her broad red silk belt embroidered with gold, as well as her handful of brushes of varying shapes and sizes – one dipped in the same saturated red as her sash – bring a balancing touch to the work’s muted refinement. Painted in 1790 to join the greats adorning the Vasari Corridor at the Uffizi while she was touring Italy, her portrait is supremely confident. Yet, the aristocratic world that made her was crumbling, the fury of the French Revolution forcing her into a 12-year exile. Vigée Le Brun’s meteoric rise to fame, and her career as one of the 18th century’s foremost portraitists, was set against a turbulent historical background.

Marie Antoinette and her children (1787), Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun © Photo : RMN-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

This exhibition features important loans from leading institutions, such as the Louvre, Metropolitan and Hermitage Museums and the Palace of Versailles. A breathtaking display at floor level of her 1787 family portrait of Marie Antoinette – which failed to restore the Queen’s reputation on the eve of the Revolution – offers an opportunity for close inspection impossible in its usual lofty position in the Salon de Mars at Versailles. The exhibition’s greatest strength, however, lies in the fact that nearly half the pictures have been drawn from private collections and are on public display for the first time. More intimate in scale and character than her official commissions, these works brought new freedom and immediacy to her portraiture. Some are movingly personal, such as her 1787 portrait of her seven-year-old daughter Julie, painted in profile but looking straight at the viewer through her reflection in a small mirror; some are strikingly sincere, such as her pastel of the Duchesse de la Rochefoucauld, an alluring if not conventionally beautiful intellectual; while some are unexpected, such as her 1788 portrait of a towering Mohammed Dervich Khan, ambassador of the sultan of Mysore.

Gabrielle Yolande Claude Martine de Polastron, duchesse de Polignac (1782), Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun © Photo : Rmn-Grand Palais (Château de Versailles) / Gérard Blot

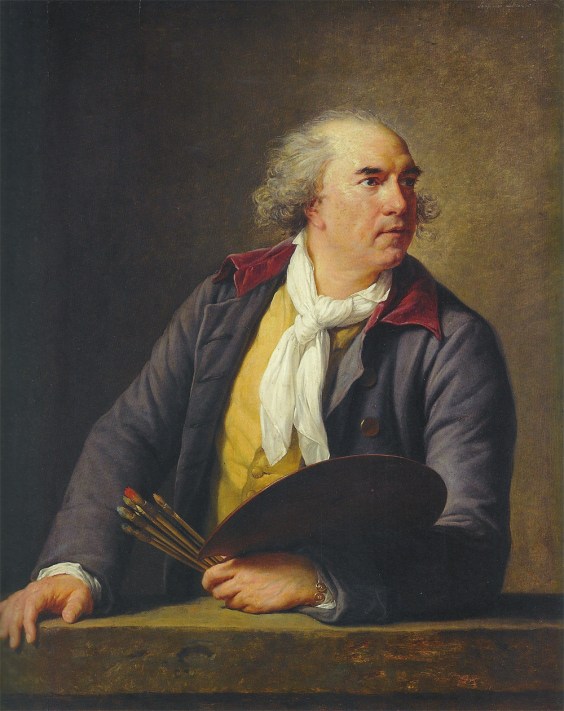

The set of rooms dedicated to her portraits of the French aristocracy in the 1780s – a world of privilege, luxury and pleasure that was about to shatter – is testament to the exquisiteness of her art. Her rendering of fabrics is breathtaking, ranging from the provocatively informal dress of the Duchesse de Polignac, to the sumptuous embroidery on the silk jacket of the Comte de Provence (both portraits 1782). Her female models take on increasingly indolent poses, such as in her 1783 portrait of Madame Grand, whose distracted eyes and parted lips imbue her with what contemporary commentators called ‘bewitching sensuality’. Vigée Le Brun did not sacrifice character to fashion however, as attested by a bold 1788 portrait of her friend, painter Hubert Robert. Palette and brushes in hand, he does not look at the viewer but seems absorbed by his thoughts, itching to return to a painting of his own.

Hubert Robert (1788), Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun Musée du Louvre, Paris

The revelation of this exhibition are the less well-known portraits painted during Vigée Le Brun’s emigration (1789–1802) to escape the French Revolution. While her paintings contain no historical references, they offer a human insight into this turbulent period. A pair of portraits of Adélaïde and Victoire, the only two daughters of Louis XV to survive the French Revolution, has been reunited for the exhibition. The two sisters sat for her in July 1791 in Rome having just heard of Louis XVI’s humiliating capture, and Vigée Le Brun was unable to hide a profound sense of sadness and distress.

She found a completely different atmosphere at the Hamilton’s in Naples in 1792, where she represented Emma as a bacchante dancing in front of Mount Vesuvius. Later that year in Venice, her émigré friend Dominique Vivant Denon introduced her to his lover, Isabella Teotochi Marini. Vigée Le Brun’s resulting small, tightly framed and economically painted oil on paper portrait of Isabella is one of her greatest achievements. Draped in a brilliant red cloak highlighting her pale complexion, her hair loosely held by a ribbon built up of red and white flecks of paint, Isabella looks right into her viewers’ eyes, wrapped in a magnetic erotic energy. Vigée Le Brun was able to provide her friend with an intimate picture she knew would keep the fire of their relationship burning after his return to France. Denon, who went on to become the Louvre’s first director under Napoléon, cherished the picture until the end of his life.

Isabella Teotochi Marini (May-June 1792), Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. The Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo

Vigée Le Brun reached Saint Petersburg in mid 1795 and was finally able to rekindle the sort of life she had left behind in Paris, noting later in her Souvenirs: ‘Every evening I went out into the world. Not only were the balls, concerts, plays frequent, but I delighted in the daily gatherings, where I found all the urbanity and grace of French society; for, to use an expression of Princess Dolgorouki, it appeared as though good taste had hopped from Paris to Saint Petersburg’. Generous loans from Russia such as the huge and opulent 1795 portrait of 16-year-old future empress of Russia Elisaveta Alexeïevna, and a 1797 portrait of Princess Catherine Ilinitchna Golenichtcheva-Koutouzova, wrapped in a red shawl, her black curls swept back in the wind, attest to this wonderful refinement.

Princess Catherine Ilinitchna Golenichtcheva-Koutouzova (1797), Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

This memorable exhibition tells the story of a remarkable artist and independent woman who transcended social hierarchy, and established herself in an overwhelmingly male-dominated profession, where she portrayed great women (and men) from Versailles to Naples, Saint Petersburg to London. Vigée Le Brun’s paintings bear witness to the establishment of a new world order with an undying sense of optimism, exquisite skill, and an acute eye for fashion. Yet she had never been the subject of an exhibition in her native country until now. Curators Joseph Baillio and Xavier Salmon have gone out of their way to right this wrong by bringing together a truly exceptional array of paintings.

‘Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun 1755–1842’ is at the Grand Palais, Paris, until 11 January 2016. An abridged version of the exhibition will then travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, (9 February–15 May 2016) and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, (10 June–11 September 2016).

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home