LACMA has received a grant from the TEFAF Museum Restoration Fund to analyse and restore a devotional work by Melchor Pérez Holguín – a project that ought to transform what we know of the Bolivian master, says curator Ilona Katzew

When acquired in 2019, Pietà became the first work by Melchor Pérez Holguín to enter the LACMA collection. What motivated the acquisition?

It’s the first major Bolivian work to enter our collection. We’ve been building the collection of Spanish colonial art for some 15 years now. One of my goals has been to diversify our holdings, so when the opportunity arose to acquire the Pietà, I was thrilled – not only because it’s a painting by one of the most singular South American masters from the late 17th and early 18th centuries, but also because the work is simply stunning.

Aside from the older collections of Spanish colonial art in the US, which have been gathering this material since the 1930s – such as the Brooklyn Museum or the Denver Art Museum – institutional collecting in this field in North America is for the most part a fairly recent affair. There are a small number of works by Holguín in private and public collections, but he’s not generally well represented in the US.

Pietà (c. 1720), Melchor Pérez Holguín. Image courtesy the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

Holguín is sometimes described in the archives as the ‘Brocha de Oro’ [‘golden brush’]. What sets his work apart from that of his peers?

One of the most distinguishing elements of his work is the figures’ gaunt exaggerated features. They are infused with a level of pathos you seldom see in contemporaneous works. The expression ‘brocha de oro’ was first used to describe Holguín in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s not how he was referred to during his lifetime – but he was very well known.

He fulfilled commissions for a number of religious orders in Potosí [part of the Viceroyalty of Peru], including for the Jesuits and the Mercedarians, as well as for the indigenous parish of San Lorenzo. When the Jesuits were expelled from the Americas in 1767 by King Charles III, the agency administering the Society’s assets ordered an inventory of its church in Potosí – and if you look at the list, from the nearly 300 paintings recorded the only artist referred to by name is Holguín. It’s a very telling detail that suggests how well regarded he was in those days, which is also confirmed by his many imitators.

Potosí was an important city in the 18th century, far above sea level and wealthy thanks to the silver mines of its Cerro Ricco (‘Rich Mountain’). How refined was its artistic culture, and who would Holguín’s clients have been?

The Imperial Villa of Potosí was referred to as the ‘Treasure of the World’, and was a place that attracted people from all over the globe – many surely enticed by the idea of striking it rich in the Americas. It was one of the most polyglot and mixed societies of the early modern world. Because of the unlimited riches it was often described as a dissolute place. But it was also a profoundly devout city, dotted with churches and other religious institutions that had been established since the discovery of the mines in the 16th century. That’s where Holguín comes into play. Although he was born in Cochabamba, by 1678 he’s documented in Potosí, where he supplied images for many of these institutions; he was obviously catering to both a local and an international clientele. Some of his works were exported across the Viceroyalty of Peru, and even beyond it – the Museo de América in Madrid, for example, has one of the most important works by him, showing the ceremonial arrival in the city of Viceroy Morcillo. Holguín boldly portrayed himself in the middle, holding his palette and brush to suggest his elevated status and that of his profession.

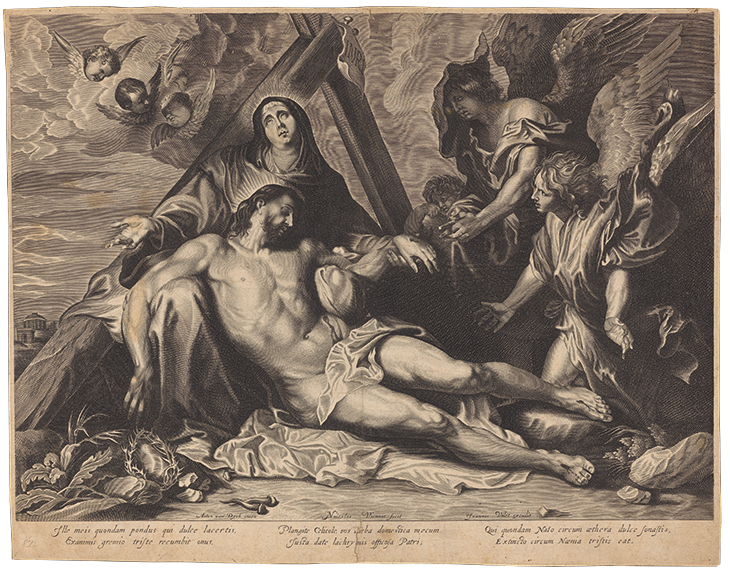

This painting is loosely based on a print after Van Dyck. How influential was print culture for the artists of the viceroyalty?

Prints were an easy way to transport images – not just from Europe to the New World, but across Europe, too. It was not only prints that made their way to the New World, though, but also painted copies, so it can sometimes be hard to determine what an artist was looking at: Antwerp and Seville produced a number of painted images that were also destined to go to the viceroyalties. It’s important to recognise that artists in the New World were not operating from the margins but were enmeshed in this larger ecosystem of the production of images and their circulation between Europe and the New World. Spanish colonial art has often been described as derivative – but it’s not. There’s a whole process of referring to images, then interpreting, combining, and transforming them, which is key to understanding the production of the region, as well as its originality.

Pietà (c. 1630), Nicolas Viennot (after Anthony van Dyck). Image courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

How does Holguín make Van Dyck’s composition his own?

He takes the main compositional elements of the Van Dyck into account, but infuses the image with an enormous sense of pathos that can be seen in the figures, with tears trickling down their faces, and through the addition of the wonderful cherubs who lament the death of Christ. He also turns the image very deliberately into a nocturne, which intensifies its narrative purpose. He’s drawing from local traditions, too: the strategic use of green and red reminds me of other paintings from Upper Peru, including the Cusco School. This colour combination, associated with the Inca rulers in ancient times, is transposed to the divine Christian cohort – which is highly suggestive. The lavish use of gold leaf is something that we’re planning to look into in more depth, to see whether it was used by Holguín or was a later addition, given how popular this technique was at the time, particularly in Cusco.

Why do we know so little about Holguín’s technique?

It’s largely due to the lack of previous scientific analysis of his works, I think. This field is really taking off (our colleagues from the Fundación TAREA in Buenos Aires, for example, have examined a number of paintings with illuminating results), and scholars are more attuned to issues of materiality and the impact it can have on the way we interpret images, but there’s still not enough information to fully understand the technique of an artist like Holguín or even to make attributions in a concerted way. So there’s a lot that we still need to learn; I’m hoping this grant will allow the conservators at LACMA to trace the type of pigments used and determine whether the gold was applied by Holguín or a later hand. It should give us tools to help us learn more about his style, technique, and his choice of materials.

We’re only in the initial phases of the conservation project, so it’s hard to predict the outcome, but the idea is to approximate the work’s original splendour. Our team of conservators, led by Joseph Fronek, is highly respectful of the paintings they work with and aim to understand as much as possible about the artist’s intentions before undertaking treatment. I hope we will all benefit from their findings, continue building on them, and enjoy the outcome.

Ilona Katzew is Department Head and Curator, Latin American Art at LACMA.

After conservation, Pietà will go on display in ‘The Eye of the Imagination: LACMA’s Collection of Spanish Colonial Art’ at LACMA in 2021.

From the March 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home