Hardwick Hall has always been acknowledged as a very singular house, unique in plan and containing outstanding original decoration and contents. Its patron, Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury, commonly known as Bess of Hardwick, has been celebrated as a formidable patron of early modern Europe. This new study, comprising 20 chapters and several appendices by leading scholars in their respective fields, gives credit to the huge amount of scholarship that the house has already attracted, yet here builds a narrative of further subtle character. It is superbly illustrated throughout and was expertly steered through the press by Sally Salveson. While the house remains the most perfect example of the late Elizabethan age, here we are shown its context among the other houses of Bess’s life, most notably old Chatsworth; the partnership she formed with her favourite son and co-habitee, William Cavendish; and the hitherto uncharted interventions into the fabric and contents by later centuries. The subtitle of the book reminds us that the house may be an ingenious invention of its time, but it looks back to the medieval past and its image has also been shaped by a somewhat false sense of its being a time capsule. Though it later became just a secondary house of the Cavendish family, it was cared for, cherished, and imperceptibly altered in the process.

Queen Mary’s Room, which has a dado bearing the date 1599, was probably originally the Inner Chamber for the Best Bedchamber. Photo: © National Trust Images/Nick Guttridge

The role of the architect of the building, Robert Smythson, is sufficiently but not exhaustively dealt with here, partly because the work of Mark Girouard has already established Hardwick’s context in Smythson’s larger body of work. Rather, examination of the house here reveals more changes in the course of construction than the structural integrity has long encouraged us to believe. In the key chapters on the architecture, Nicholas Cooper (to whom we effectively owe the existence of this book, so long did he champion the need for a further great study) offers the comparison of other building types such as hunting lodges, which partly explain the novelty of plan and function. Cooper establishes that the new solution of a transverse hall starts in the adjacent Old Hall, also built at Bess’s instigation immediately prior to the New Hall, as a solution to the constrictions of the site. He emphasises that the Long Gallery at the top of the house, hitherto often described as a rarely used space under the owner’s lock and key, can be accessed in three ways, from both public and private parts of the house. He points out that for all the comprehensiveness of the 1601 inventory, the secure point of reference for so much previous scholarship, the north end of the second floor with its grand state rooms is still puzzling as to the identification of some of the original spaces. For the first time Cooper outlines where there is consistency in the treatment of mouldings in the wooden internal fittings, identifying thereby some patterns of work by individual craftsmen.

Historians have given many interpretations of Bess’s true intentions in building the house and decorating it in the way that she did, including the claim to the throne of her granddaughter Arbella Stuart and the possibility of a visit by Elizabeth I. The latter was surely highly unlikely by the 1590s (indeed the Queen never travelled as far north from London as this during her entire reign) but the book discusses, through the tapestries, embroideries, and paintings, the presence of another Queen, Mary of Scots. She had been executed by the time Bess began the New Hall, but the shadow of her captivity for many years under the guardianship of Bess’s fourth husband was always significant at Hardwick, through the myths associated with rooms supposedly named for her, and by the fact that she surely saw the earliest of Bess’s great pieces of furniture during her captivity at Chatsworth and may even have recommended the sourcing of the French pieces.

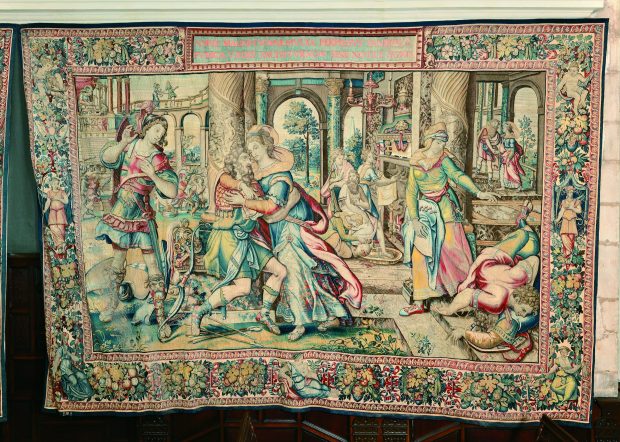

The Homecoming of Ulysses from the Story of Ulysses, c. 1550, Niclaes Hellinck after a design attributed to Michiel I. Coxie. Photo: National Trust Images/Robert Thrift

The various chapters establish a fascinating pattern of cross-referencing in the decorative and applied arts in this house. Much of this is due to the continental print sources they all share, discussed here by Anthony Wells-Cole. These prints were probably purchased by William Cavendish for the skilled people employed here – especially John Balechouse, suggested here as the equivalent of a royal ‘sergeant-painter’ to his patrons – and put to all kinds of painted embellishment within the house. Bess, as with others of her Protestant generation, had a liking for biblical parable rather than frowned-upon scenes of religious devotion. Her favourite classical story, embodied in the series of tapestries in the High Great Chamber, was that of Ulysses, and especially the role of the constant and virtuous Penelope within that tale. The textile collection at Hardwick has always been especially valued, from Bess’s care in her will to ensure the safekeeping of the embroideries she herself had crafted, to the reassembly of the so-called Devonshire Hunting Tapestries in the late 1890s, and the sterling work of Evelyn, wife of the 9th Duke of Devonshire, in conservation.

In 1957 the house passed to the National Trust through the settlement of the Cavendish family’s death duties after the death of the 10th Duke some years earlier. The house has been well cared for ever since. As, however, the opening pages of this volume remind us, for all the studies that have been made of Hardwick over the years the single most authoritative source for Hardwick’s history has been the extended National Trust guidebook written by Mark Girouard and first published in 1989. The Trust spent a decade or so commissioning guidebooks with a full architectural and family history, and with short catalogues of contents, but has long ceased to do this at many sites. It is encouraging therefore that this is the second of what I hope will be a great series on the Trust’s most significant houses (the present book was preceded by that on Ham House in 2013), in which meticulous scholarship and careful re-examination of house and contents will be the starting point both for future research and the necessary care and conservation of the whole.

Hardwick Hall: A Great Old Castle of Romance, edited by David Adshead and David A.H.B. Taylor, is published by Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and the National Trust

From the February issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home