What if we eliminated the term ‘abstract art’ from our conversations about modern painting and talked only about individual painters and particular pictures? Would the discourse about painting become freer, more productive, less tendentious?

That’s what Philip Guston suggested, mid-conversation, in 1958, and the potential of that idea always hummed at the back of his brush. The youngest of seven children, Guston was born Phillip Goldstein, in Montreal, in 1913, the year The Rite of Spring premiered in Paris, and he died of a heart attack in 1980, the year after Jean-François Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition was published. His life traced that of modern art itself, and he played almost every role available: satirical cartoonist, New Deal muralist, core member of the New York School, Zen-tinted existentialist and then, for the last act of his life, some blistering hybrid of them all – a visionary chronicler of late 20th-century America.

When Guston was ten, he found his father, an LA junk man, hanging from the garage ceiling. Soon after, his mother bought him a mail-order cartooning course, and in high school he was kicked out, along with his friend Jackson Pollock, for drawing comics that mocked the English department. He taught himself to paint, looking at books and local collections, while playing bit parts in B-movies. In September 1933, aged 20, Guston exhibited at the Stanley Rose bookshop and its gallery, including his now lost painting Conspirators. A critic in the LA Times wrote that Guston was ‘jazzing Michelangelo’, an epithet that could equally describe his final dozen years as an artist.

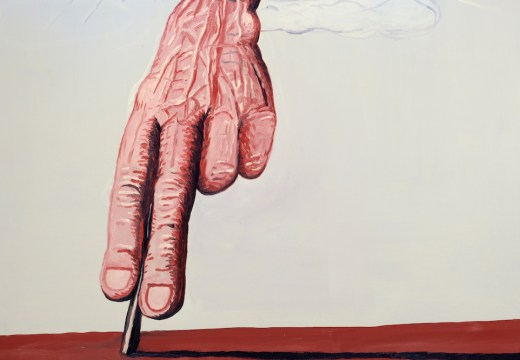

By the late 1960s, Guston had left the New York School and found a way to fuse American modernity, with all its wit, violence and improvisational genius, to the Old Masters. He loved Italy and its art and spent two extended periods in Rome, but he was also a product of the New World, the child of penniless émigrés who had fled Odessan pogroms. He digested the elegance of Piero della Francesca and other Renaissance masters, combined their idealism with goofball comic books and Hollywood, and gazed unsparingly at American decadence, never omitting his own guilt and fragility from his vision. And it’s this world – the KKK hoods, the creeping injustices, the jalopies, the open books, the death-haunted eyeballs, the bottles and the worn-out shoes, all painted with a swift, masterly hand – that is conjured by the artist’s name today.

The Street (1977), Philip Guston. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: The Guston Foundation

Despite Guston’s perennial relevance and popularity, there isn’t a single, comprehensive volume that surveys his life and work. The closest book to fulfil that role, Robert Storr’s brief but excellent introduction, Guston (1986), is more than 30 years old. Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting fills the gap admirably, with a clear, chronological text by Storr, a section of writings by the artist, and generous, plentiful reproductions that make it by far the most expansively illustrated tome on the market. The book also features a superb ‘Chronology’, tracing Guston’s milestones through personal letters and reviews, with photographs, invitations and other ephemera, assembled from the artist’s archive by editor Amanda Renshaw.

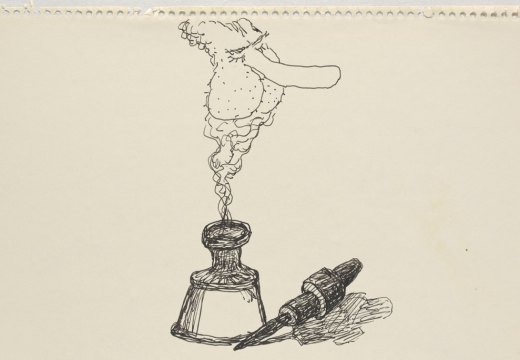

The first chapter, ‘A Wandering Jew Sets Out’, sets the tone of the book: here’s the story of a plucky autodidact on his picaresque journey through America’s most tumultuous and triumphant era. Storr deftly delineates the wide range of influences in Guston’s pantheon, showing for instance how John Cage’s interest in Zen introduced Guston to the Japanese monk Sengai Gibon (1750–1837), whose ink drawings delighted in paradox and human folly. He is particularly good on the period between 1960 and 1966, when Guston painted inchoate heads shifting anxiously in silvery-grey seas of pigment, which are, in my view, among the most haunting and beautiful works the artist ever painted. Guston’s late ’60s breakthrough and the aftermath of the infamous exhibition at Marlborough Gallery, New York, in 1970 are deftly handled, but when he arrives at the final few years of Guston’s prolific and uneven output, the sheer number of paintings seems to outpace Storr’s commentary. This is not a surprise, for the later ’70s featured some extraordinary masterpieces, such as The Line (1978), but also more than a few paintings that feel exhausted, sodden with muck and mortality. It’s not an easy period to assess as a coherent body of work, and perhaps there’s work yet to be done there.

In a more personal final chapter, ‘Guston after Guston’, Storr reflects on Guston’s legacy and his own history and engagement with Guston’s work over almost 50 years. In one passage he addresses what he views as Ross Feld’s ill-considered dismissal of Guston’s abstract work (Feld, in his book, calls Guston a ‘shamming, less-than-committed abstractionist’). Storr has a point: one cannot simply put aside Guston’s abstract work because we now think of him as the artist who flamboyantly rejected the New York School. Guston always had a vivid and distinctive voice as a painter, whether in the chunky effulgence of Native’s Return (1957) or the clarity of the acrylic and ink works on paper he painted months before he died. Storr concedes that Guston’s ‘second act’ secured his place in art history, and he is understandably loath to underestimate Guston’s achievement as an abstract artist, or even disparage, as a painter of abstracts himself, the mode at all. But we cannot ignore how forcefully Guston expressed his frustrations about abstraction. ‘I can’t find any freedom in abstract art,’ he said, or, ‘every time I see an abstract painting now I smell mink coats.’ Abstraction reeked of death and decoration, of purity and absolutes.

Native’s Return (1957), Philip Guston. Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Photo: The Guston Foundation

There’s no doubt that Guston liked to look at abstract art. He loved Mondrian. But he also revered Rembrandt, revelled in junk, villains, drama, the communal mood of the kitchen table, the crowded bar, the anxious classroom. He called Piero and Mantegna ‘grand abstract artists’. Guston turned his back on abstract art because he loved to talk, and the conversation will always be better in a fallen, damaged world, among the image makers.

Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting by Robert Storr will be published by Laurence King Publishing in September.

From the May 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home